There is Something About Exports: and It Is Productivity

Pakistan’s exports are low

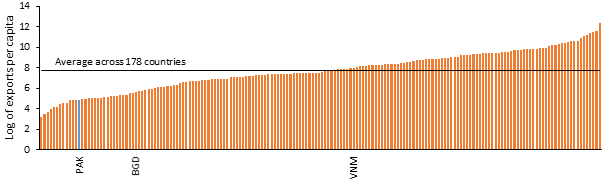

In per capita terms, Pakistan exported 130 USD in 2019, less than half of Bangladesh’s, and less than 20 times less than Vietnam’s per capita exports (Figure 1). They are low because they have been stagnant for too long. Pakistan’s exports today are only 55% greater than they were in 2005. Vietnam’s are 8 times greater.

Source: World Development Indicators, World Bank

There is something that is making exporting less attractive for Pakistani firms

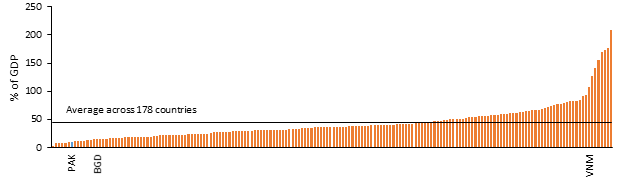

Private sector growth faces several challenges in Pakistan. Energy availability and reliability, access to credit, or the complexity of the business climate to name a few. Yet, these challenges affect both exporting and production for domestic consumption, which has been growing faster than exports. Indeed, exports accounted for 14.3 percent of GDP in 2005, but for 10.1 percent of GDP in 2019, placing Pakistan among the ten least export-oriented economies in the world (Figure 2). So, there is something about exporting that is a challenge. This blogpost argues that the core of the problem lies at the intersection of low productivity and high trade costs.[1] Two problems that feed each other, forming a vicious circle.

Source: World Development Indicators, World Bank

For firms to be able to export, their productivity needs to be high

Productivity needs to be high enough to allow them to successfully pay for the trade costs associated with exporting.

Getting more firms to export requires either increasing productivity or reducing trade costs. Or both. It so happens that the latter leads to the former. International evidence shows that when it gets easier to trade – being because you can get intermediate inputs and capital equipment at world prices, because export intelligence is efficiently provided, or because Customs, ports and logistics work seamlessly, then, more firms export. And they export larger volumes. What’s more, as they export and compete with sophisticated players worldwide, they end up learning how to produce better. This is also true in Pakistan. In a recent paper we examined how publicly listed firms in Pakistan fared in terms of productivity, and we focused specially on this interaction between trade costs and productivity. We unveiled three key findings.

First, internationally linked firms are exceptional performers

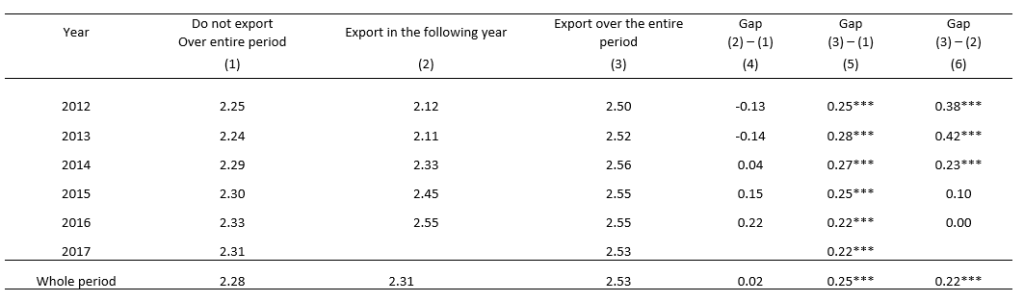

Those that export (and also those that are partially or totally foreign owned) tend to do (much) better than those that are oriented to the domestic market or that are domestically owned. This is a common finding across countries. Interestingly, in Pakistan, the productivity gap between those that never export and those that systematically export is 25 percent, most of which is explained by exporters becoming more productive as they export more systematically (Table 1). This is suggestive of a process of learning by exporting.[2]

Note: authors calculations based on the listed firms’ dataset. Difference in means test are reported with significance at *10%, **5%, ***1%.

Source: Lovo and Varela (2020)

Second, increased import duties reduces firms’ productivity

Increased import duties – particularly, but not exclusively, levied on intermediates – reduces firms’ productivity. This is also a common finding across countries. Accessing intermediates at world prices is crucial to expand set of options firms have when choosing how to produce and this helps them find an efficient way of doing things. Efficient duty drawback mechanisms have been a game changer for Bangladeshi exporters, for example. Our results also suggest that import duty exemption schemes in place for exporters in Pakistan, that allow them to get refunds of duties paid on intermediates used to produce exportables, do not completely solve the problem.

Exemption Schemes Remain Complex

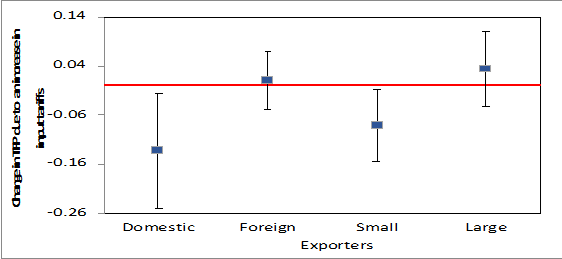

In part, because despite some progress on the matter, the system to claim exemptions remains complex, inducing some exporters – particularly the relatively smaller ones – to opt out of it. In part, because often, the domestic market acts as a platform to experiment before venturing in global markets, but it is only exporters that can avail to the duty exemptions. This is why we found that, in Pakistan, domestic oriented firms and the relatively small exporters face productivity declines when import tariff on inputs go up, but foreign-owned, or large exporting firms are relatively immune to input tariff changes (Figure 3). Thus, while improving these exemption schemes is important, it is no substitute for an across-the-board tariff rationalization reform.

Note: graph show regression coefficients (and 95% confidence intervals) of firm-level productivity (TFP) on input tariffs by type of exporter. The coefficient shows the effect of a 1 percentage point increase in input tariffs on TFP

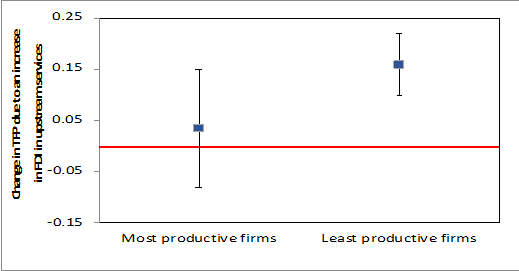

Note: graph show regression coefficients (and 95% confidence intervals) of firm-level productivity (TFP) on FDI in upstream services by type of firms. The coefficient shows the effect of a 1 percent increase in FDI on TFP.

Third, a dynamic and efficient services sector is crucial for productivity of manufacturing firms downstream

A dynamic and efficient services sector is crucial for the productivity of manufacturing firms downstream, and therefore for their international competitiveness. We found that firms operating in downstream markets benefit from increased FDI in upstream services sectors. The gains are larger for relatively less productive firms (Figure 4). Likely because this is associated with more varied, better quality, or cheaper services inputs that are necessary to produce efficiently downstream – think telecoms, software development, marketing, or sophisticated transport and logistics solutions.

All in all, results show productivity-based export growth requires further efforts to reduce trade costs

Both in goods and services. So, what to do? Improving import duty exemption schemes is important – and progress towards automation has been made (the introduction of FASTER is an example) – but it is no substitute for an across-the-board tariff rationalization reform. The current efforts of the Government in this area are promising. Promoting export orientation through the provision of export intelligence to new exporters coupled with active investment promotion initiatives focusing on efficiency seeking investments, will boost productivity growth. Coordination between BoI efforts and TDAP are likely to pay off. Also, easing restrictions – de jure or de facto – for foreign investments, particularly in modern services, will prove useful.

[1] There are other challenges, such as energy prices and energy reliability, access to credit, or the complexity of the investment climate. Yet, these challenges affect both exporting and production for domestic consumption, which has grown faster than exports, as revealed by the decline in the ratio of exports to GDP from 14.3 percent in 2005 to 10.1 percent in 2019.

[2] Something similar happens for firms that are foreign owned. Foreign owned firms are more productive than domestically owned firm. That is the case because foreign investors ‘cherry pick’ more productive firms in the first place, but also because their productivity improves after they are acquired. See Lovo and Varela (2020) for more details.