A Review of Accountability Systems: Learning from Best Practices

Nasir Iqbal & Ghulam Mustafa[1]

1.Background

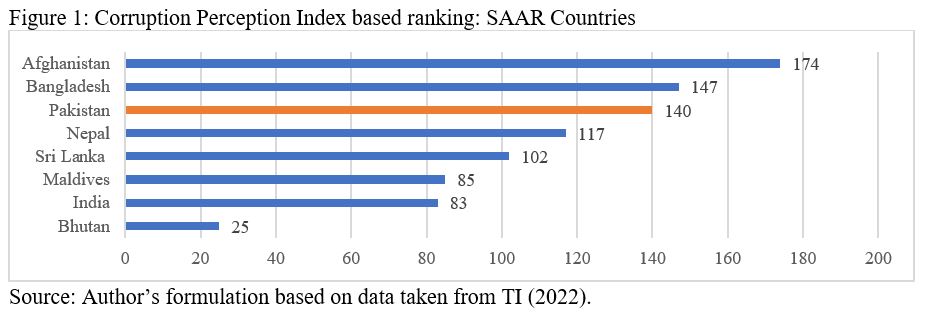

Over the last two decades, ‘accountability’ has become Pakistan’s most famous political slogan (Mehboob, 2022). Despite numerous reforms in the accountability system, Pakistan got the worst ranking in the region based on the Corruption Perception Index (CPI) published by Transparency International (TI) (TI, 2022).[2] The CPI-based ranking shows that Pakistan ranked 140th out of 180 countries in 2021. Pakistan ranked well below the South Asian economies (Figure 1).

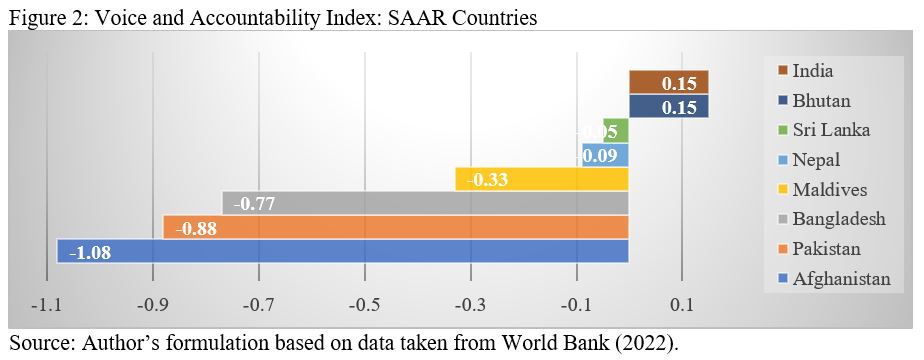

Pakistan established numerous accountability systems to reduce corruption. However, Pakistan’s performance in implementing accountability is poor. The index to measure vertical accountability is called Voice and Accountability Index (VAI)[3]. Their values range between -2.5 (weakest accountability) and +2.5 (strongest accountability). Pakistan’s score is well below the South Asian average (-0.36) (Figure 2). Pakistan has had weaker vertical accountability over the years. All values of the VAI are found to be less than zero, demonstrating that Pakistan has failed to implement strong vertical accountability (World Bank, 2022).

___________

[1] The views and opinions presented in this brief are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the Institute (PIDE). The authors are thankful to Amna Raiz and Maria Ali for their support as a Research Assistants in collecting background information and secondary data from various sources. The financial support is provided by PIDE through Research Assistantship program.

[2] The Corruption Perception Index (CPI) ranks economies based on “how corrupt their public sectors are perceived to be.” The index ranges from 0 to 100, where 0 is highly corrupt and 100 is very clean (TI, 2022).

[3] The index for Voice and Accountability captures perceptions of the extent to which the citizens are able to participate in selecting their government, as well as freedom of expression, freedom of association, and a free media.

___________

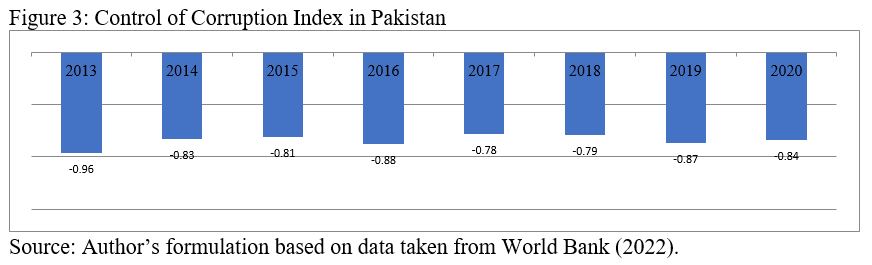

The Control of Corruption Index (CCI)[4], which measures the horizontal accountability for countries, also does not show encouraging performance in Pakistan. The CCI discloses that values for the CCI for all years are found negative, which is indicative of the adverse performance of Pakistan on horizontal accountability. Horizontal accountability is perpetrated through the institutions like NAB and Anti-Corruption in Pakistan.

The existing accountability system, especially National Accountability Bureau (NAB), led to political instability and dwindling economic growth and prosperity in the country. Apart from the poor performance of accountability systems, we heard voices from media, politicians, and even the judiciary against selective accountability, political victimization, political engineering through unjust accountability tools, and misuse of authority by the officials. Given this background, this brief aims to understand the structure of the accountability system with a particular focus on NAB in Pakistan. The brief also aims to review global best practices to provide legislators with a way to reform Pakistan’s accountability system.

2. What is accountability?

Accountability is used for surveillance and oversight of the exercise of power. The term “accountability” often refers to the discussion of public governance or its transparency (Philip, 2009; Boyce & Cindy, 2009). The question of accountability arises when there is a concern about the abuse of public office – which almost every government or institution across the globe. According to Maile (2002), accountability is a two-dimensional concept: answerability and enforcement. Answerability implies that public officials are answerable for their actions. Accountability in public governance transcends beyond the answerability in the form of information generation and its justification. It contains the components of enforcement which refers to rewarding the right doers and punishing the wrong doers (Domina and Parfenova, 2019). The question of accountability arises when there is a threat to the general use of power in public governance or administration matters. Establishing anti-corruption agencies is the response when accountability seems to be at stake at the behest of the public interest. The seeming simplicity of response poses a lot of difficult questions. The unchecked and rampant corruption militates against the core of democracy and democratic institutions like parliament, judiciary, and civil service (Berggren and Bjornskov, 2020).

_________

[4] The index for Control of Corruption captures perceptions of the extent to which public power is exercised for private gain, including both petty and grand forms of corruption, as well as capture of the state by elites and private interests.

_________

Broadly, there are three institutional modes to pursue accountability: vertical and horizontal, and diagonal accountability. Vertical accountability is electoral accountability, which the people do through elections to the incumbent governments. In contrast, horizontal accountability is perpetrated by the state authority to bring to the book for misappropriation of the authority, grabbing the money by using its authority, and all other means of corruption. They are establishing NAB or other Anti-Corruption departments in the form of horizontal accountability. The media and civil society do the diagonal accountability to hold the incumbent government accountable. These modes of accountability play a significant role in stopping the misuse of authorities and contributing to sustainable economic growth and development (Walsh, 2020). The institutional school of thought argues that accountability fosters economic growth and prosperity (Nawaz, 2015; Iqbal et al., 2012). However, we must be specific to gauge the modality of the NAB, being the most prominent horizontal mode of accountability (Ahmed, 2020; Imran, 2020).

3. Horizontal Accountability: The case of the NAB

NAB was established in 1999 to deal with the investigation and prosecution of white-collar crimes, which happened to be public office holders, politicians, and citizens who have been accused of having abused their powers or depriving the national treasury of millions under section 5(m). According to Section 2 of the NAB ordinance, National Accountability Ordinance (NAO) shall come into force from the first day of January 1985.

In February 2002, the government launched National Anti-Corruption Strategy (NACS) project to survey and assess international anti-corruption agencies and their models. NACS, based on global best practices, presented a need to rethink and revise the anti-corruption narrative. Therefore, the government made relevant amends in NAO. With the revised NAO, the NAB has been entrusted with the investigation and prosecution of crimes and prevention and awareness against them. So, the NAB is the premier anti-corruption organization in Pakistan, with a sole mission to eradicate corruption and corrupt practices. It mandates holding those accused of such practices accountable during an elaborative investigative process (Javed, 2021).

Box 1: The United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC)

The UNCAC – the only legally binding universal anti-corruption instrument- also demanded that a member state have an effective anti-corruption agency or organization. Therefore, the NAB is an internationally recognized anti-corruption agency for Pakistan under the UN charter. NAB considers all the offenses that fall under National Accountability Ordinance (NAO) under section 9(a). Offenses have been highlighted below as there is a need:

To educate society regarding the threats and causes of corruption and corrupt practices and to implement policies for its prevention. |

3.1 Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) of NAB

Besides awareness and prevention, enforcement is also one of the NAB’s strategies to cope with corruption. NAO mandates NAB to adopt a three-pronged approach for curbing corruption in the country.

Stage 1: Complaint Verification: NAB’s Enforcement Strategy functions on the admission of written complaints or information by NAB about an alleged act of corruption. In stage one, the initiation of the process begins with the verification of the contents of the information. The contents of the information are verified in light of law provisions. This process is known as complaint verification (CV). At the same time, a complainant is summoned for the confirmation of status and evidence available to him. Once confirmed that the alleged act of corruption falls under NAO and the information procured justifies to move forward, and it is processed further for subsequent action.

Stage 2: Inquiry: Section 18(c) of NAO 1999 speaks of inquiry for the collection of oral and documentary evidence in much formal way, and the scope of the inquiry is reasonably enlarged, and experts are engaged in case the need arises, i.e., banking experts, revenue experts, corporate experts, etc. Their statements are recorded, and preliminary reports are obtained regarding the commission of the offense if any. The investigation officer and the legal experts scan the evidence and reports furnished and obtained before the above-mentioned experts. The decision is taken considering the collected evidence if any offense is made. According to section 25(a), the option of Voluntary Return (VR) is made to the accused persons during the inquiry without entailing the consequences of section 25(b), which is a Plea Bargain.

Stage 3: Investigation: Upon digging out the evidence against the accused person(s) and assessing the same as trial-worthy evidence to stand the test of cross-examination by the defense lawyers at the trial, the inquiry mentioned above is upgraded to the investigation, which is to be concluded expeditiously and preferably within 90 days. Upon completion of the investigation, if the chairman of NAB is satisfied and decides to refer the matter to the accountability court in the form of a reference upon receipt of the reference to the concerned accountability court. The court proceeds accordingly, and the trial proceeds in the code of Criminal Procedure, 1898. Suppose evidence collected during inquiry investigation is insufficient to file a reference against the accused person(s) or set of accused persons. In that case, the investigation is closed to their extent only under section 9(c). Suppose an accused person or a set of accused persons want to avail of the option of a plea bargain under section 25(b). In that case, he may do so, and if accepted by the chairman of NAB.

The acceptance of Plea Bargain and its approval by the accountability court shall be deemed a conviction carrying all the consequences of section 15 of the NAO minus the jail sentence. To lend credence to the inquiry or investigation, the accused is allowed to explain or tell his side of the story in respect of the allegations that surfaced or the material collected against him. The accused is also free to place any documentary or oral evidence in favor of his defense. As for the SOPs and the judgments of superior courts, the version of the accused is analyzed, given the NAB’s Enforcement Strategy begins with an initiative of fact-finding without having to blame any person for an alleged act of corruption.

The entire process has been designed to move with an explanation from the complainant for the clarification of charges pressed against the accused to assess whether their position falls in line with material evidence. Suppose the version stated by the accused is found plausible in lieu of the supporting evidence. In that case, the benefit of the same is given to him. For verification, the evidence collected vis-à-vis allegations are verified against the explanations given by the accused and the recorded statements from witnesses.

Regional Bureaus are the operational arms of NAB, which are actively involved in field operations such as CVs, inquiries, and prosecution of cases at trial and appealing stages. The Operations Division and Prosecution Division at NAB Headquarters support the smooth conduct of operational activities per law and the standing operating procedures (SOPs). Under NAO, the chairman of NAB has been authorized to file references anywhere in Pakistan, keeping in view the smooth prosecution of the case and convenience of placing evidence before the concerned court without jeopardizing the accountability process in general at the hand of the accused person who is very powerful, and they tend to destroy the evidence over raw witnesses and influence the court and the prosecution (Tariq & Mumtaz, 2021).

Box 2: Reforms/Amendments in NAB Ordinance: History

NAB Ordinance 1999: The NAO 1999 was promulgated on November 16, 1999. The objective was to tackle corruption by taking legal actions against corruption (NAO, 2002). Nonetheless, the pending proceedings and cases fell under Ordinance No. XX of 1997 and the Ehtesab Act, 1997 were continued. The primary purpose of the NAO 1999 was not only to take adequate measures against corruption but also to take measures to recover the outstanding amount from the guilty. Following are the key takeaways from the said ordinance.

NAB Amendment Ordinance 2002: In 2002, the NAO 1999 was amended. Under this amendment, any person or public office holder can voluntarily come forward and offer to return the assets and gains before the commencement of the investigation against that person. This amendment allows the NAB chairman to accept such volunteer offers after determining the due amount. It is not the person offering a plea bargain; it is the discretion of the chairman of the NAB (NAB Ordinance, 2002). The rest of the setting is the same as in NAO 1999. NAB Amendment Ordinance 2021: The PTI government amended the NAB ordinance in 2021. The following are the key points of the NAO amendment 2021:

NAB Ordinance Amendment 2022: PML(N) led coalition government introduced the following amendments in 2022

|

4. Learning from global best practices: The case of Hong Kong & Singapore

Our study takes practices perpetrated by Hong Kong and Singapore as references—Anti-Corruption Agencies (ACA) in the Asian Pacific region, Hong Kong’s Independent Commission against Corruption (ICAC), and Singapore’s Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau (CPIB). The discussion on these two accountability institutions is weaved up as follows.

Since its establishment in 1974, ICAC has enjoyed astounding success in its fight against corruption and is often quoted as a “Universal Model” (Heilburn, 2006; Lam, 2009). ICAC came into being when corruption was known to be systematic among high-level officials and police officers, which fueled prostitution, drug trafficking, and gambling in lieu of hefty returns. The legal framework of which ICAC is part has been made to be as clear, detailed, and effective as possible. According to a recent ranking, Hong Kong ranks 12th among 180 countries on Corruption Perception Index (CPI) for 2021. It controls corruption with the help of three functional departments: Investigation, prevention, and community relations. The investigation is done through Operations Department, which is

responsible for investigating. The Corruption Prevention department is responsible for creating awareness, funding research related to the implication of corruption-related policies, conducting seminars for business leaders, and helping public and private institutions formulate strategies to reduce corruption.

The role of the Community Relations Department is to spread awareness in society regarding the societal costs of corruption, which is pursued through launching multiple campaigns against corruption (Speville, 2010). The institutional hierarchy comprises a special administrator, ICAC director, and three oversight committees. The ICAC submits regular reports with procedural guidelines for investigations, confiscation of property, and inquiries durations, whereby the oversight committee ensures that all investigations are carried out with integrity. When the ICAC was established, it did not have a credible record. Nonetheless, Hong Kong has known to be the least corrupted in East Asia (Owusu et al., 2020; Tsao and Hsueh, 2022).

On the other hand, Singapore’s Corruption Practices Investigation Bureau (CPIB) was established in 1975, focusing primarily on investigation and enforcement. The function of CPIB was to receive and investigate complaints about corruption in the public and private sectors. Their prevention function is responsible for screening candidates before appointments in civil service statutory boards to appoint candidates with clean conduct, hence working in a corruption-free environment within CPIB (Hutahaen and Pasaribu, 2022).

4.1 Benchmarking CPIB and ICAC performance

There are myriad reasons why Hongkong ICAC and Singapore’s CPIB are successful because they have firm support in and out of government in carrying out these core missions. Even in totalitarian regimes, the hierarchical influence goes a long way to influence how an ACA should work. Yap (2022) suggests comparing outcomes based on the following indicators.

- Corruption Perception Index (CPI): Hong Kong and Singapore rank 12th and 4th in CPI for 2021 out of 180 countries.

- Expenditure Per Capita and Staff-Population Ratio: Agency indicators are used to see whether the agency has been provided with adequate personnel and budget by their governments to perform their functions.

- Credibility and Independence: The benchmarking identifies four pre-requisites in analyzing the performance of ACA: independence, permanence, coherence, and credibility.

5. Restructuring the NAB

Multiple internal and external factors hamper accountability in Pakistan, including:

5.1 Internal factors

Delay has emerged as one of the leading factors in concluding the inquiries in investigations. Due to the complex and vast scope of the NAB ordinance, oral or documented evidence collection is quite cumbersome. Although the NAB is fully empowered to collect evidence, the influential accused persons do everything they can to hide the truth and delay the investigations by conceding documents and concealing/stealing the original record.

- When the trial proceeds, the procurement of evidence is another arduous task because the generally very resourceful accused tend to prevail.

- The potential witnesses deviate from their statement earlier given to the NAB under investigation. The witnesses who exhibit the official record before the courts are also very cooperative.

- The transfer postings of the judges and the NAB officials, concerned NAB officials, and other government officials concerned with the trial are also one of the problems contributing to the delay. It takes 2 to 5 years to conclude the prosecution before the accountability court.

- A Long-drawn, cumbersome, and time-consuming legal process generally takes almost 20 years for an accountability case to get adjudicated by the apex court and get concluded either in favor of the prosecution in case of conviction or the favor of the accused, resulting in acquittal. The law prescribes that an accountability court complete the trial within 30 days, and the appeal shall be disposed-off within 90 days.

- In the case of absconding of one or some of the accused persons before the accountability court, the declaration of absconding takes about 5 to 6 months before the accountability court before the regular trial gets underway as per the mandate of the criminal procedure court.

- The numbers of accountability courts are also not enough to cope with the rush of work. Moreover, the prosecution is under-resourced and short of the number of prosecutors to deal with the factum of delay.

5.2 External factors

- Relying on corrupt political leaders to handle corruption

- Using NAB as an “Attack Dog” against political opponents: According to Transparency International (TI), the NAB lacks operational autonomy because of the government’s dependence on weaponizing NAB against its political opponents. It has often been accused of being a partisan agency used for political victimization by the incumbent governments. The National Accountability Ordinance (NAO) 1999 has given NAB abundant operating authority and powers. But in reality, it is not free from political pressures.

- Lack of mainitaning transprancy by the NAB.

6. The way forward

The discussion demonstrates that Pakistan is experiencing poor performance on all global indices, which measure corruption and vertical and horizontal accountability in Pakistan. Moreover, the common perception among judiciary and civil society is that the NAB is used for political manipulation against the opposition leaders. The following points are important to improve the transparent performance of the NAB.

- There is a dire and unavoidable requirement to change the NAB’s structure. All political parties, civil society representatives, and lawyers’ bars and associations prepare the legal and institutional structure of the NAB so that the transparent accountability system may be promulgated.

- This is the era of digitalization, and the NAB must be trained and technologically well-equipped to build its capacity and skillful human resource to hatch the agenda for creating a transparent and inclusive accountability system.

References

Ahmed, E. (2020). Accountability in Pakistan: An Academic Perspective. ISSRA Papers, 1(XII), 1-14.

Berggren, N., & Bjørnskov, C. (2020). Corruption, judicial accountability and inequality: Unfair procedures may benefit the worst-off. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 170, 341-354.

Boyce, G., & Davids, C. (2009). Conflict of interest in policing and the public sector: Ethics, integrity and social accountability. Public Management Review, 11(5), 601-640.

Domina, A. A., & Parfenova, D. A. (2019). The notion of corruption in the civil service. Modern Science, (10-1), 80-82.

Heilbrunn, J. R. (2006). Paying the Price of Failure: Reconstructing Failed and Collapsed States in Africa and Central Asia. Perspectives on Politics, 4(1), 135-150.

Hutahaean, M., & Pasaribu, J. (2022). Bureaucratic Reform and Changes in Public Service Paradigm Post-Decentralization in Indonesia: 2001-2010. KnE Social Sciences, 795-810.

Imran, Y. (2020). State of public accountability in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) in light of international best practices. City University Research Journal, 10(1).

Iqbal, N., Din, M., & Ghani, E. (2012). Fiscal Decentralisation and Economic Growth: Role of Democratic Institutions. The Pakistan Development Review, 51(3), 173-195.

Javed, D. S. (2021). Assessment of Anti-Corruption Agency of Pakistan. Journal of Contemporary Issues in Business and Government| Vol, 27(3), 1399.

Lam, J. T. (2009). Political accountability in Hong Kong: Myth or reality?. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 68, S73-S83.

Luqman, M., Li, Y., Khan, S. U. D., & Ahmad, N. (2021). Quantile nexus between human development, energy production, and economic growth: the role of corruption in the case of Pakistan. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 28(43), 61460-61476.

Maile, S. (2002). Accountability: An essential aspect of school governance. South African journal of education, 22(4), 326-331.

Mehbood, A. B. (2022) Accountability fails again, The DAWN, https://www.dawn.com/

Nawaz, S. (2015). Growth effects of institutions: A disaggregated analysis. Economic Modelling, 45, 118-126.

Owusu, E. K., Chan, A. P., Yang, J., & Pärn, E. (2020). Towards corruption-free cities: Measuring the effectiveness of anti-corruption measures in infrastructure project procurement and management in Hong Kong. Cities, 96, 102435.

Philp, M. (2009). Delimiting democratic accountability. Political Studies, 57(1), 28-53.

Tariq, S., & Mumtaz, T. (2021). Lack of Transparency and Freedom of Information in Pakistan: An Analysis of government’s functioning and realistic policy options for reform. Pakistan Journal of Social Research, 3(3), 70-76.

TI (2022). Corruption Perceptions Index 2022 Methodology. Transparency International Available at: https://www.transparency.org/.

Tsao, Y. C., & Hsueh, S. J. (2022). Can the Country’s Perception of Corruption Change? Evidence of Corruption Perception Index. Public Integrity, 1-13.

Walsh, E. (2020). Political Accountability: Vertical, Horizontal, and Diagonal Constraints on Governments, Policy Brief (22), V-Dem Institute, Department of Political Science University of Gothenburg, https://www.v-dem.net/

World Bank (2022) Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI), https://databank.worldbank.org/

Yap, J. B. H., Lee, K. Y., Rose, T., & Skitmore, M. (2022). Corruption in the Malaysian construction industry: investigating effects, causes, and preventive measures. International Journal of Construction Management, 22(8), 1525-1536.