Developing a Policy Solution for Khokhas in Islamabad

Developing a Policy Solution for Khokhas in Islamabad

Fizza Khalid Butt and Fahd Zulfiqar, Pakistan Institute of Development Economics, Islamabad.

-

INTRODUCTION

The process of development leads to large scale rural-urban migration as the poor seek opportunities in cities. We have seen Pakistan has now become the most urbanised society in South Asia.[1] Yet, Pakistani city planning remained clueless about this important fact about development.[2] To date both courts and city planning want to keep Pakistan as a rural pastureland made up of suburbs without city centres (Haque 2015,[3] Haque and Nayab 2020).[4],[5] The poor who make the city work have never received recognition from the city planners.

Islamabad as capital of Pakistan was designed in 1959 by a Greek architect-planner, Constantinis A. Doxiadis. Islamabad provides a very interesting locale as the city’s master-plan illustrates a template against which informal practices can be articulated (Tauhidi and Chohan, 2020).[6] In addition to illegal squatting and temporary housing, commercial activities are also the reason for various forms of encroachments. Informal trading includes street vending such as hawking of goods carried out on sidewalks, roads, and commercial buildings.

Street vending in Islamabad dates back to the 1960s when the city was barely modernised as per modernist master-plan and when there were only a few shops set up in the remote villages of Bari Imam and Saidpur. Islamabad’s municipal authority, Capital Development Authority (CDA) asked people to set up food stalls for labour class and construction workers. Such stalls, called kiosks or khokhas in Urdu language, continued to meet basic needs of the poor even before the construction of the country’s capital as per Doxiadis’ vision. With the construction of planned commercial markets in Islamabad, CDA attempted to relocate khokhas in smaller spaces such as a Class-III shopping centre (ground-floor shops). Very few khokha owners were allotted such spaces in mid-1970s. In 1980s, first comprehensive policy to formalise khokhas by CDA was planned for which CDA conducted surveys to prepare a list of khokhas to allot temporary licenses. It was also planned that eventually khokhas will be granted permanent allotments. This thinking received criticism because according to city’s master-plan and municipal by-laws, allowing licences for commercial activities in spaces which are strictly designed for non-commercial activities was considered ‘unlawful’.

Carrying out businesses in such spaces are called encroachments in streets and green belts. The process of issuing temporary licenses and permanent allotments has also received criticism for practical and processual reasons. For instance, influential and well-connected businessmen who are entering khokha business, are able to secure licenses and allotments in prime locations whereas those who had spent long in the business still await for allotment letters. In 2012 a case filed against a functional khokha in F-7 markaz of the city, sparked a debate on the fraudulent ways licenses and allotments are done. It also highlighted involvement of rich businessmen who by using their social and political capital are able to secure licences and allotment of land. This debate has also triggered the issue of existence of khokhas, their pros and cons, the advantages of their existence and the need to safeguard their rights. Given the complex interplay of law, land, and informal businesses in Islamabad, understanding encroachment in the light of by-laws is critical. Box 1. helps in detailing the concept of encroachment as per CDA’s documents.

___________________________

[1]Using satellite images, Reza Ali (2013) showed that Pakistan may be as much as 70 percent urban.

[2]Master-planning of cities is pursued even though most cities in Pakistan are fragmented under many different administrations such as municipal authorities, development authorities, cantonments and other areas. Local government is such a contentious issue making the drive to consolidate city administrations very weak.

[3]Haque, Nadeem, (2015). Flawed Urban Development Policies in Pakistan. PIDE Working Papers. PIDE.

[4]Haque, Nadeem and Nayab, Durre. (2020). Cities: The Engines of Growth. PIDE

[5]The Supreme Court has outlawed all city establishments that were not in masterplans that are decades old and had no room for accommodation for city growth.

[6]Tauhidi, Amna. and W. Chohan, Usman. (2020). Encroachment & the mystery of capital: A Pakistani context. Center for aerospace and security studies. CASS Working papers on Economics & National Affairs.

-

THE QUESTION OF ENCROACHMENT

| BOX 1: EVOLVING ENCROACHMENT IN ISLAMABAD No person shall encroach on the land under the charge of the authority or put up an immovable structure, hut or khokha or overhanging structure under any circumstances. Free flow of pedestrian traffic in circulation verandahs of all the markets of Islamabad shall not be obstructed by stacking articles or in any other manner. Articles so stacked shall be liable to be removed and confiscated at the cost and risk of the defaulter. Monthly licence for roofless movable stalls can be issued but also revocable by 12 hours-notice.[7] Similar document also says: · The licence as granted will not be transferrable. · In case of revoked license, the articles (such as sale and furniture, to name a few) will be removed by the licensee within 12 hours. In case of non-compliance, the articles shall be removed by the authorised officials at the cost and risk of the licensee with no compensation granted. · The area of movable encroachment should not exceed 16 sq. ft. for which rent at the rate of PKR. 1 sq. ft. per month shall be paid. · A person will be liable to punishment of fine which may exceed to hundred rupees in case of violation of any of the bye-laws stated in the chapter on encroachment. The amount may extend to twenty rupees per day in case of continuing contravention. ENCROACHMENT AS DEFINED BY MODEL BYE-LAWS, 2018 · Encroachment means and includes movable or immovable encroachment on public place, public property, Public Park, open space, public road, Public Street, public way, right of way, market, graveyards or drain. · Encroacher or wrongful occupier means and includes a person who has made movable or immovable encroachment on an open space, land vested in or managed, maintained or controlled by the local government, public place, public property, public road, public street, public way, right of way, market, graveyard or drain and owns the material or articles used in such encroachment existing at the time of removal of encroachment or ejectment and also any person(s) in possession thereof on his behalf or with his permission or connivance. |

‘Encroachment’ has become a big issue because of mechanical city planning devoid of needs of a growing urban centres in a developing globalising economy. City planning in Pakistan has no zoning for the poor both for their housing as well as their commerce and work. There is a large demand for labour in cities and planners feel that this labour will come from outside the city. Islamabad was the first city planned by bureaucrats who run cities, and it set the paradigm for city planning in the rest of Pakistan. This city was planned on the American suburban model with no space for the poor and mobility on wide avenues for speeding cars. The poor were to live in a neighbouring town Rawalpindi and come daily to serve Islamabad. The bureaucracy who runs Pakistani cities since local government has never been allowed to run, tried to use this model in all cities and planned for suburbs with poor labour coming from an area outside cities. In addition, cities like Islamabad were master-planned on assumptions of in-migration. Islamabad was expected to be no more than few thousand people; instead it grew to now 2.5 million people. By the master plan Islamabad has only 60,000 structured households. Needless to say the others have lived in encroachments which include informal settlements and other arrangements that CDA and the courts do not like.

City administrations are always playing rear-guard against the effects of their bad planning. Box 1 also shows how the city administration is struggling with the issue of encroachments with periodic reshaping of definitions and rules. Because of city administrations’ insistence on master-plans that are based on no population movements as well as huge emphasis on suburban housing, there are huge shortfalls in the supply of many important facilities.[8] Especially hit are the forgotten poor who cannot rent or buy expensive suburban housing for their needs. They have to defy urban planning that refuse to recognise them. For housing they are left to crowd into older parts of town and find informal slum areas. In both cases as you will see below, they risk the wrath of both the various city administrations and the courts who side with them. State power refuses to recognise or empower the poor. As city space becomes more congested with population increase and city development, the number of anti-encroachment drives (evictions with destruction of private property) has increased in recent years. City administrators also rationalise anti-encroachment drives by bringing in legal perspective. City municipality has legal right to reclaim the land which is illegally occupied. The attempt is also to reduce the resources and informal channels which facilitate in expanding informal economy arguing that this economy poses major threats to the city’s sprawling and security.

Sara (2013) in Tauhidi and Chohan (2020) lists following procedural requirements abided by domestic and international law, before carrying out anti-encroachment drives.

- The local government must provide resettlement alternatives for the evacuees which will also help avoiding the use of force, in addition to providing feasible resettlements.

- It is the responsibility of the governments to ensure that the operation does not leave people vulnerable and poor. In this regard, governments must provide housing and compensation as market value.

- Since most of the countries are signatories of international humanitarian law, it is mandatory to maintain the following:

- Notification to be dispatched prior to the scheduled date of anti-encroachment drive.

- Information regarding how the operation will be carried out and purpose due to which the land or housing will be used must be communicated prior to the scheduled date.

- A clear mechanism ensuring transparency in compensations for the poor evacuees must be articulated.

- Provision of legal aid to people in need to seek redress from courts is also mandatory.

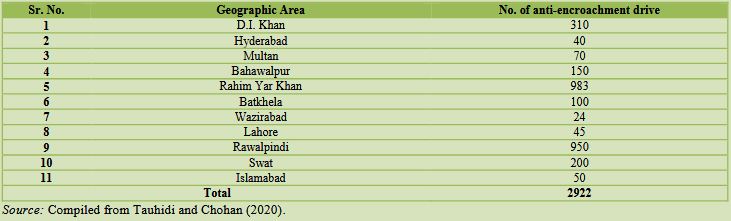

These requirements are sparsely fulfilled when viewed with respect to the number and outcome of the anti-encroachment drives carried out in the country. 2922 incidents of such operations have been identified in all provinces in 2019. Following table identifies number of anti-encroachment drives carried out in 2019 in Pakistan.

______________________________

[7]http://www.cda.gov.pk/documents/docs/islamabadLaws.pdf

[8]See PIDE Policy Viewpoint 12 for shortages in Lahore, Pakistan’s second largest city. https://file.pide.org.pk/pdf/Policy-Viewpoint-12.pdf

Despite different operations carried out in various parts of the country, 4108 acres of Railways’ land is still under encroachment (worth PKR 90 billion), with Punjab at the top (2076 acres of land), followed by Sindh (1159 acres of land), Balochistan (618 acres of land) and KP (250.9 acres of land) (Tauhidi and Chohan, 2020). In 2019, CDA removed around 6399 illegal buildings and structures; CDA’s enforcement wing in collaboration with local administration has conducted operations in around 13, 879 encroached lands by conducting 1207 operations in 2019 (Tauhidi and Chohan, 2020).

-

CONTEXTUALISING KHOKHAS FOR ISLAMABAD

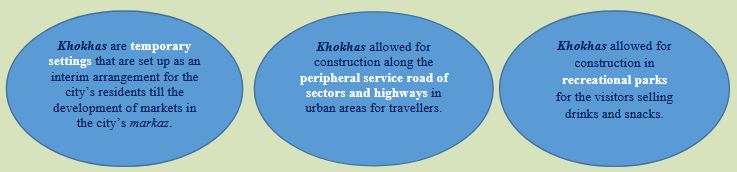

In cities khokhas provide earning for the poor. Khokhas are also an important way to protect right to business of the poor. There are 485 licensed khokhas selling grocery and food items in Islamabad which are located in F4, F6, F7 and G3 sectors of the city. The khokhas used to be a profitable business in the past. The land rent has increased from PKR 3000 to 6000 since 2008. The areas specified for khokhas have also been reduced by CDA despite the fact that as per one estimate PKR 3 crore goes in the government account through khokhas. In 1978 the Secretary of Housing and Works, Islamabad issued licenses to the khokha owners of Islamabad who provided food for the labour class. By 1986 a government policy titled ‘Policy regarding Location of Cabin Shops, Kiosks, Tea Salts and Temporary Structures in Islamabad’ was issued in which CDA’s responsibility to streamline the process for the issuance of licenses to khokhas was declared. The three types of khokhas as classified in the policy are detailed in these circles:

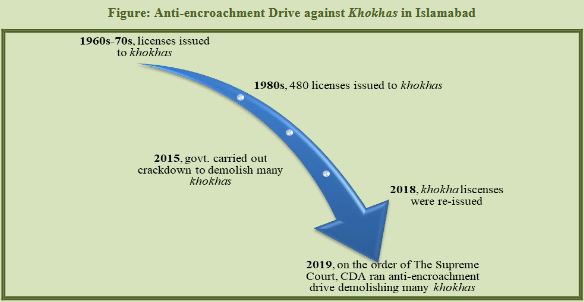

There are 485 licensed khokhas in the capital city. The representatives of khokha association revealed that currently there are 785 functional khokhas in Islamabad, including both licensed and unlicensed. Number of khokha could not be increased in Islamabad due to the issue of land which is believed to be an illegal encroachment by the khokha owners. Hence the state response to licensing or de-licensing land to khokha owners has remained consistently inconsistent (see following figure).

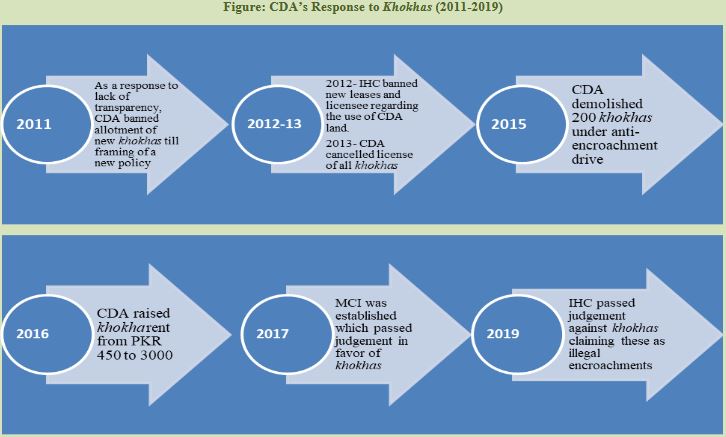

The CDA’s response to the issue of licensing and de-licensing land for khokhas has been guided by the land laws and strict regulatory framework which needs to be deregulated for self-employment of more people in khokhas. (See following figure for pictorial representation of CDA’s response to khokhas-2011 till 2019).

-

DESCRIPTIVE ANALYSIS

For the purpose of current policy viewpoint, we conducted a survey in 6 sub-locales of Islamabad. We also conducted semi-structured interviews with street vendors from all the sub-locales. Descriptive analysis of findings are detailed in the following text.

4.1. No of Khokhas

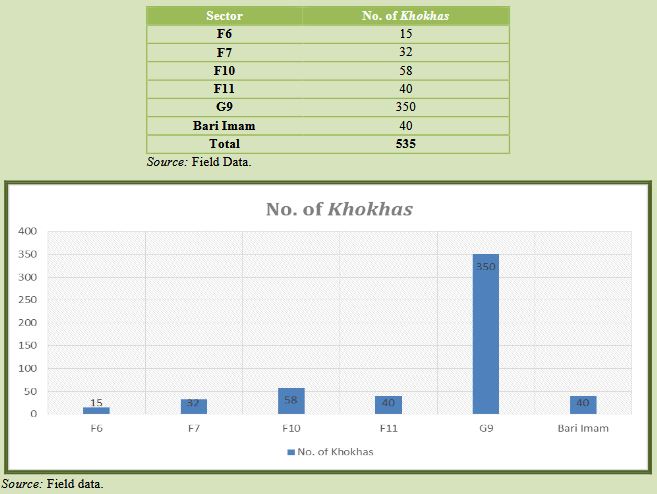

The number of khokhas in the selected locales are depicted in the table and chart below;

There are more than 500 khokhas in six locales of the city which can help infer the number of khokhas in the city itself must be somewhere around 3000. These 3000 khokhas mean 3000 families and dependency of those families on these businesses. The chart shows the maximum number of khokhas being set up at G9 Markaz which is also knows as Karachi Company and a major economic hub of the city where people from all kinds of backgrounds shop.

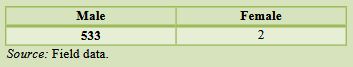

4.2. Gender of Street Vendors

The majority of the street vendors were men whereas we found two women street vendors in F7 one was selling fruits and other was selling toys. The percentage of female street vendors is less than 0.1 percent because in the particular class, men are still considered to be earning outside and women in the rarest scenario opt for street vending due to the extreme family pressure and conditions. As claimed by ladies, most of the ladies prefer working as house helps rather going out with a cart.

4.3. Age of Street Vendors

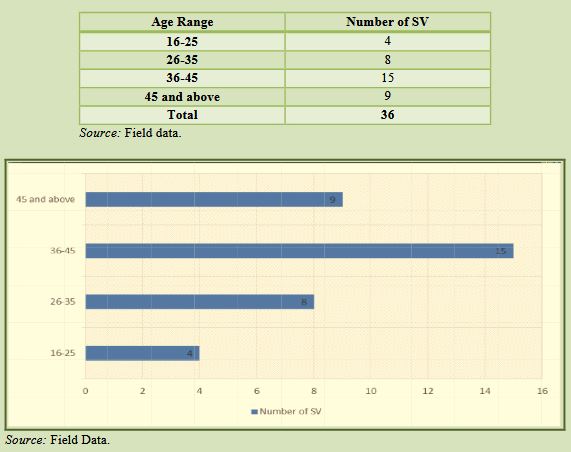

We interviewed 36 street vendors and their ages lie in the following segment, also the interviewees were chosen to be major representative of the overall population of the street vendors in the city.

Most of the street vendors fall in the age range of 35 to 45, when the responsibilities of earning a livelihood are at peak, in most of the cases they were the soul bread winners for big families including numerous children. In most of the cases they have started bringing their male children with them so they can also learn the art of selling and be able to do something of their own in the future. The rare cases where the street vendors are younger than 25 are those where they’ve been asked by their aging fathers to work for them in customer dealing in most hours of the day and the major supply related work is being done by the fathers.

4.4. Classification of Items being Sold

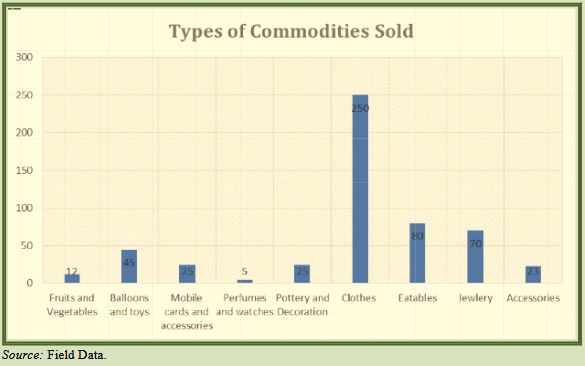

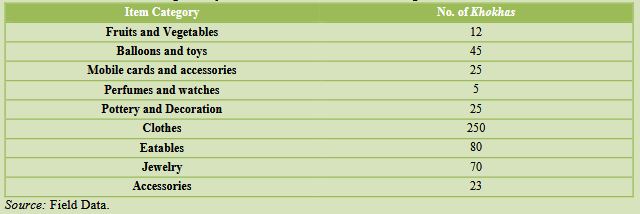

We have classified the items being sold by the khokha vendors in the following table and chart.

Street vending is not limited to the moveable carts that rove around in the streets of the city to sell and supply fruits and vegetables but they cater almost all the item categories require to live. The street vendors target the middle class at the large level.

-

DISCUSSION

The anti-encroachment activities of CDA are on rise, the number of these operations are increasing each day, and one day they’re demolishing the katchi abadis and the other day running after the khokha owners. Street vending is one of major contributors in the informal economy and is providing livelihood to number of people. There are almost 44 sectors and sub-sectors in Islamabad and the locale for this study was 6 of them and in 6 locales, we roughly found 535 khokhas (immovable and moveable). Considering the tradition of man being the bread winner, most of the khokhas are run by the men whereas the CDA representative believed the khokhas designed by CDA were planned for the widows basically where they can sell the home made food to the labour and lower working classes. Looking at the considerable size of khokhas in the major economic hubs of the city, it can be inferred that these khokhas do not operate in isolation but in a community while competing with each other and supporting each other simultaneously, creating a small economic hub for themselves.

During the course of the field work, coincidently an operation by CDA was observed in F7 markaz where it was observed that khokha owners were running with their belongings including a big hot tawa (round platter to cook rotis) in order to save their equipment from CDA. The khokha owners themselves know that they have illegally occupied the public land but they have no other opportunity, they say they have to earn and fulfil the needs of their family, they have to risk it in order to earn living for themselves. They claim they do not have enough money in order to buy or rent proper shops in the market and meet their expenses. This also leads the idea of the need of these khokha vendors, shoppers roaming around in the markets mentioned that they need to eat or munch while shopping and look for these street vendors, they often have to buy some stuff they believe is too pricey in the shops so they look for street vendors in order to buy that and get upset if the street vendors are not available in the premises. It is important to note that it is not only street vendors that are there to fulfil their needs but also the customers that need them. Given the mutual need of both the provider and buyer, why there have not been any efforts to preserve the rights of these vendors.

Illegal encroachment on anyone’s land be it public or private is an unlawful activity and requires proper action, considering this the state narrative is veracious but on the other hand this is also state’s responsibility to take care of its citizens, and to listen to the hues and cries of the under privileged, CDA has been observed to be working for the elite, as most of the operations are planned on the underprivileged rather the mafias around. It is state’s responsibility to provide for such trade zones where the street vendors can set up their stalls and earn in peace. If the reform are in the planning, they process needs to be speed up in order to save the poor street vendors from the misery.

-

POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

Based on the survey and its analysis, we would like to recommend that

- In the khokha reforms, the khokhas should not only be provided to the people whose licensed khokhas were demolished but to the other street vendors too. There can be a licensing procedure through which khokhas can be assigned to the people on a nominal fee. The fee can also help them to get rid of the exploitative rent that they are paying to the shop owners in different markets.

- There needs to be khokha trade unions too in order to safeguard the rights of the street vendors. Politics should be kept away from the economic activity of the poor.

- The role of CDA is to secure human needs irrespective of the differences. It also explicitly claims to ensure public service delivery on cleanliness, health, education, opportunities, and supply of goods in the city. The functioning and role of State and government in the indiscriminate provision of afore-said services seems to be incongruent in the light of the State-institutionalised anti-encroachment drive in Islamabad. Unless this dichotomy of the role of State and government is addressed, the poor will continue to be systematically excluded.

- Consideration for tying social service support to street vendors together by technology (ICT facilitated cell-phone use) where their economic activities and license are also bound to services they can receive for their families (education, healthcare, etc.). This brings them more into the fold of formalised social services.

- Technology should be introduced to administer and sustain the system. Adoption of GIS based strategies for comparing and monitoring support for informal sector entrepreneurs across cities and settings can be helpful. Also imperative will be to explore ICT and cell phone-based communications to bind entrepreneurs to zones of operation and the needed administrative licenses. Also important in this context is the role of ICT to give entrepreneurs the needed social support and access for their families.

- Ehsaas program in collaboration with PIDE has institutionalised a formal system and allotted spaces for khokha owners in G-11 sector of Islamabad. Such a formal institutionalisation of allotted spaces for street vending activities can be applied to other sectors of the city and all cities of Pakistan.