No Confidence in no confidence

As mainstream political parties gear up to advance what they believe will be curtains for Prime Minister lmran Khan – once, of course, the OIC Conference is over –it is worth reflecting upon Pakistan’s political trajectory, or lack thereof. Islamabad seems to be bracing for impact in what promises to be an eventful, and potentially turbulent end to the month of March as momentum builds towards the No Confidence Motion. Despite all the hullabaloo, however, a cursory look underneath the surface suggests little to no fundamental changes. An entire political ‘moment’ in the works with virtually no participation from ordinary folks … is this a ‘movement’ or mere theatrics from the powers that be?

Pakistan’s history has been mired by a wide array of problems, but perhaps most significantly by the phenomenon known as elite capture. Defined as, “actors who have disproportionate influence on the development process as a result of their superior social, political or economic status,” elite capture can be seen as the prime symptom of a deeper, more pathological problem: that of perverse incentives within the country’s major institutions – which have largely remained unchanged from colonial times. This is important because the governance mechanisms which defined that period were designed for two primary purposes: control and extraction.

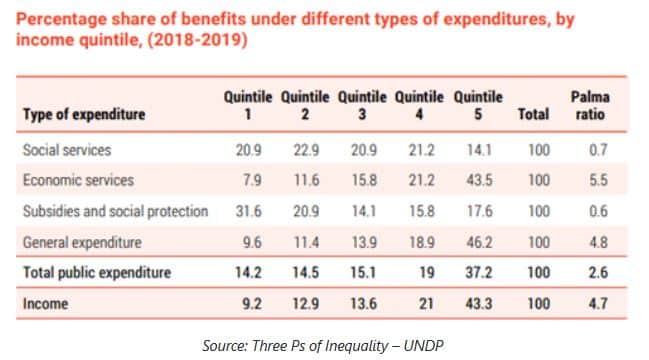

The power elite within Pakistan, including feudalists, big corporations, exporters, high net worth individuals, and top-brass within the military, are all responsible for losses of approximately Rs. 2.7 trillion to the economy on an annual basis according to a report by the UNDP. This is achieved through three primary means: favourable prices, low rates of taxation (particularly on income), and preferential access to spaces, people, and resources in order to ‘get things done’ – largely in pursuit of personal objectives. Even when it comes to government expenditures in areas such as social services, economic services, subsidies, social protection, etc., benefits largely accrue to the most affluent, i.e. the 5th quintile in terms of income – signalling widespread capture of the state by propertied classes.

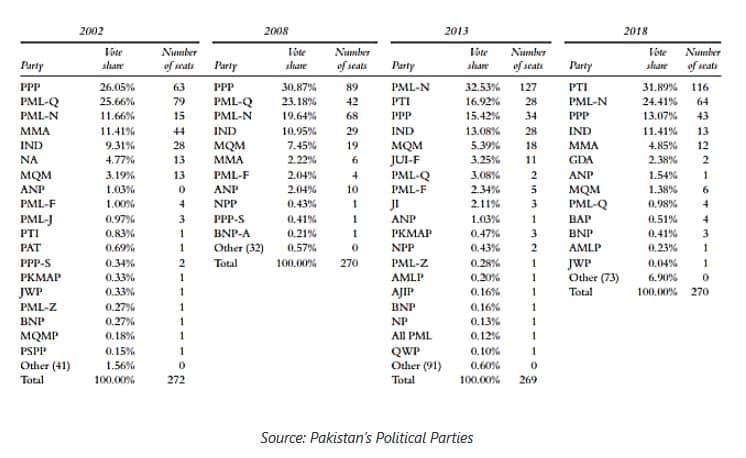

On the other hand, Pakistan’s political parties seem to have operated throughout the country’s history in a myopic, opportunistic manner

– looking to maximize their hold over power while ensuring little to no accountability to voters. Since 2002, for instance, the Pakistan People’s Party has won 229 out of 1081 seats in the National Assembly- approximately 22 percent. The Pakistan Muslim League N, on the other hand, has held approximately 25 percent. In more recent years, the Pakistan Tehreek e lnsaaf has entered the fold, winning about 27 percent of total seats over the previous two electoral cycles.

What is interesting to note here is that despite this dominance, each of these parties have had to resort to forming coalition governments in alliance with smaller parties -thus resulting in having to dilute their ideologies and overarching principles in order to accommodate new friends, something that naturally slows down the decision making process and leaving the playing field ripe for corruption, petty gamesmanship, and little incentive for service delivery- external meddling notwithstanding.

Rather than delving into these fundamental questions -of democratic representation, institutional reform, rule of law, inclusive cities, national sovereignty, etc. – Pakistan’s parties are more than content with the current status quo. One scathing example of the perverse nature of governance in Pakistan is the constant emphasis on ‘national security’ – for which the government recently put out a ‘National Security Policy 2022-26’ outlining its allegedly unconventional, multipronged approach to tackling external as well as internal threats. However, perhaps the most glaring danger of all – that of indebtedness to international financial institutions, which have played a leading role in formulating the country’s economic policy since the first structural adjustment program under General Zia – was left out of the discussion entirely.

As things currently stand, entrenched political elites have little incentive to pursue radical structural reform at any level -• largely because even when out of power, they remain connected to the corridors in some capacity, serving an assigned purpose and constantly posturing for attention from the king maker. If this were not the case, simple political moves such as pursuing empowered local government, ensuring frequent intra party elections, and maintaining transparency in terms of financial flows, to name but a few, would have been non-controversial issues with unanimous backing. Not so, unfortunately. Instead, parties spend months (and inordinate amounts of resources) on policies such as the mandatory use of electronic voting machines in polling stations – something rare even in the most developed parts of the world due to the possibility of gamification.

While mainstream parties engage in lining their pockets, ordinary citizens are left to fend for themselves, everybody from women, religious minorities, and the poor are constantly under threat from patriarchal norms, religious fundamentalism, and an economic system designed to divide and marginalize. In the words of academic and political activist Dr. Ammar Ali Jan in his book, Rule by Fear, “… it would be fair to say that [the elites] are heading the most successful ‘separatist movement’ in the country, a movement that seeks to insulate itself from the squalor and abandonment reflected in the experience of millions of Pakistanis.”

In a seminal paper by Dr. Daron Acemoglu titled, ‘Institutions as the Fundamental Cause of Long-run Growth,’ he states the following. “Economic institutions encouraging economic growth emerge when political institutions allocate power to groups with interests in broad-based property rights enforcement, when they create effective constraints on power-holders, and when there are relatively few rents to be captured by power-holders.” In other words, societies cannot possibly progress unless the incentive structures that govern its primary institutions are geared to promoting efficiency, cooperation, and inclusivity. In Pakistan, our setup is ripe for rent-seeking, elite capture, corrupt practices, and vulnerabilities to external influences loaded with political intent.

Regardless of what comes to pass over the next couple of weeks, the struggle for the strengthening of civil society must continue. Faces occupying important government offices are constantly in flux. Real lasting change can only come when those in power are aware that underperformance will mean its ouster: which only true democracy can ensure. Without the right to speech, to assembly, to trade, and to association, no number of policy prescriptions will suffice to help propel Pakistan forward. Source:

References

References

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. A. (2005). Institutions as a fundamental cause of long-run growth. Handbook of

economic growth, 1, 385-472.

Pakistan National Human Development Report 2020. https://www.pk.undp.org/content/pakistan/en/home/library/hu–

man-development-reports/PKNHDR-inequality.html

Shafqat, S., Jones, P., Khan, T. M., Naqvi, T., Malik, A., Chacko, J., … & Waseem, M. (2020). Pakistan’s Political Parties:

Surviving Between Dictatorship and Democracy. Georgetown University Press.

Jan, A. A. (2022). Rule by Fear by Ammar Ali Jan. Folio Books