Primary School Literacy: A Case Study of the Educate a Child Initiative

Primary School Literacy: A Case Study of the Educate a Child Initiative

Abbas Moosvi, Pakistan Institute of Development Economics, Islamabad.

-

INTRODUCTION

According to the Pakistan Social and Living Standards Measurement survey of 2018-19, approximately 51 percent of the population of Pakistan has successfully completed their primary level education – a figure that rose 2 percent from 2013-14. Balochistan was the worst performing province in this regard, with figures actually declining from 33 percent in 2013-14 to 31 percent in 2018-19—and the COVID-19 pandemic has likely caused further damage. Punjab, on the other hand, was the best performing, with a completion rate of just 57 percent—approximately 3 out of 5. Assuming that education and literacy are public goods, these statistics indicate a looming crisis for Pakistan: which has not managed to formulate a comprehensive strategy or framework around which children may become literate and empower themselves economically.

-

OUT-OF-SCHOOL CHILDREN: A CRISIS OF POLICY

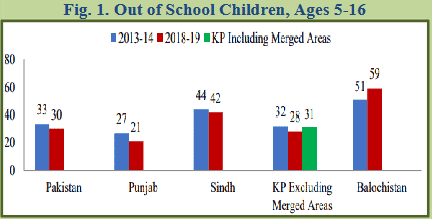

The proportion of children out-of-school between the ages 5-16 stood at a whopping 30 percent nationwide in 2018-19. In Balochistan, the worst performing province, the figure stood at 59 percent during the same period: approximately 3 out of 2 children deprived of basic education. In Sindh, the rate was 42 percent—alarming for the province generating the highest tax revenues in the country, largely from the economic capital: Karachi.

Breaking down the data further, it was discovered that approximately 1 in 4 (23.45 percent) children between the ages of 5–16 in Pakistan had never attended school—whereas about 7 percent had enrolled and dropped out. The situation in Balochistan and Sindh was the worst. In the former, about half of children in the same age bracket had never attended school (54.25 percent) and in the latter the figure stood at 35.44 percent.

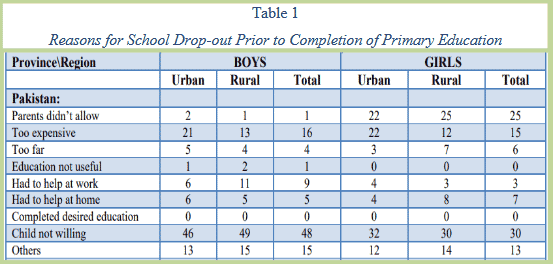

An investigation into the reasons/justifications for drop-outs was also conducted by the PSLM, which uncovered the following information.

The salient takeaways from the data are: (a) that parents are much more reluctant to allow their daughters to attend school (25 percent) rather than their sons (1 percent), (b) that ‘child not willing’ was overall the most significant factor in obstructing literacy rates for both genders (30 percent for girls and 48 percent for boys), and (c) that economic barriers in terms of a lack of affordability was a significant hurdle for both genders (15 percent for girls and 16 percent for boys).

-

EDUCATE A CHILD INITIATIVE

In June of 2021, International non-profit organisation, Alight completed a seminal development project on the education of out of school children in Pakistan—successfully managing to enrol over a million kids over the span of 3.5 years with the generosity of the Education Above All Foundation in Qatar and assistance of its various local partners. 94.67 percent of these children were enrolled in formal schools, the remainder in non-formal—in 56 different districts of Punjab, Sindh, Balochistan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Gilgit Baltistan, and the Islamabad Capital Territory. Of these children, 46 percent were girls and 54 percent were boys—indicating that gender disparities were kept at a minimal. Beyond this, a whopping 86.63 percent of these students were successfully retained.

The remainder of this policy viewpoint will outline the EAC consortium’s strategy in terms of social mobilisation, technical innovation, stakeholder engagement, capacity building, curriculum design, and non-formal schooling—with the objective being to chart out a framework for the resolution of OOSC through creative, transparent, accountable, and effective development that leverages the best aspects of both the public and private sectors.

________________________________

Authors’ Note: We acknowledge research assistance provided by Mr Saud Abdullah (MPhil Economics and Finance Scholar, PIDE).

3.1. Obstacles to Education

Taking data in this form as its starting point, the EAC consortium identified 8 key bottlenecks to the education of primary school children—areas that necessarily had to be addressed through innovative means in order to mitigate drop-out rates and incentivise families to send their children to school. They are as follows. (Alight, 2018)

Sociocultural and economic barriers. These include a dismissive attitude on the part of parents about the importance/benefits of education relative to its costs, low maternal literacy levels (particularly in rural areas), the prevalent idea that girls in particular need not attend school and ought to help with household duties until they can get married (at an early stage). Furthermore, a significant proportion of parents perceive education to be far too expensive. This is made all the worse when opportunity cost is taken into account, whereby a certain percentage of household income which is generated by child labour (largely of boys) is foregone if they are sent to school instead. Also, the cost of school supplies (uniform, kits, textbooks, stationery, etc.) and conveyance to and from schools (which are in many cases located far from homes) adds to the expense of education for families—rendering it unaffordable for most.

Lack of awareness and significant divide between communities and authorities. Most rural communities are scattered and find themselves alienated from governing authorities—particularly in the education sphere. This divide results in a lack of awareness about the avenues available to enrol children into schools, meaning that the few parents that are indeed willing to educate their children find it difficult to actually do so. This is made worse by a lack of clarity about the nature of collaboration between various government departments, corporate entities, and development sector organisations that are involved in terms of specifying their unique roles and responsibilities for any given project/initiative.

Poor quality. Parents are also reluctant to send their kids to school due to having observed the poor learning environment (school infrastructure, boundary walls, drinking water, latrines, etc.) and lack of school equipment. This is exacerbated by the fact that a large percentage of public school teachers lack basic training and struggle to impart knowledge to their students in an efficient, effective, interactive manner.

18th Amendment and an unstructured devolution of education. Following the 18th amendment to the constitution of Pakistan, the responsibility for education was devolved to the provincial level. However, the process behind this has remained disappointing and non-standardised—leading to various important institutions such as the Basic Education and Community Schools department as well as the National Commission for Human Development remaining operational at a federal level.

Mobility. One reason for low enrolment rates in primary schools is that rural communities are situated too far, with little to no avenues available to travel. This was worsened with the onset of COVID-19 and the accompanying school closures, which further restricted mobility for both children as well as teachers—leading to widespread disruptions in education and rising drop-out rates. A lack of infrastructural capacity, both in terms of supply (availability) and demand (affordability), also rendered virtually impossible the option of pursuing online education and other dynamic teaching methods.

3.2. Solutions by EAC and Policy Recommendations

3.2.1. School Enrolment

Through a series of collaborative agreements between public and private entities involved in this initiative, school enrolments were conducted through five primary means:

- enhancing the capacity of existing public schools through the construction of new classrooms with costs divided equally between Alight and the provincial governments.

- eliminating financial barriers to education via subsidising costs and offering a monthly stipend to attend.

- constructing new non-formal schools in rural communities targeted primarily at girls.

- enhancing the development of infrastructure to improve the learning environment.

- incorporating village education communities into the mix in order to establish operational hours that were most in line with the community’s requirements/convenience.

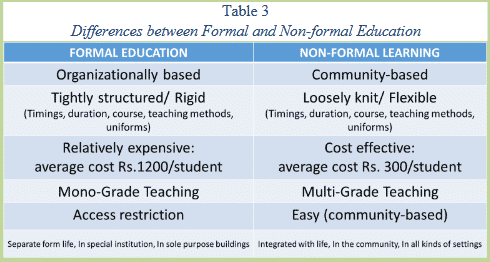

Non-formal schools. These are single-teacher schools, usually comprising of one room established within a rural community, running a multi-grade system through accelerated learning programmes—hence overcoming mobility related restrictions and reducing the cost of schooling. These schools were established through partnerships with the Non-formal Basic Education department and Directorate of Literacy, as well as Basic Education Community Schools and other local-level partners. The salient differences between formal and non-formal streams of education are presented in Table 3.

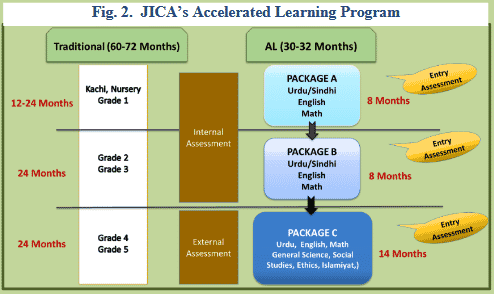

The Japan International Cooperation Agency was the EAC consortium’s primary partner in terms of the curriculum that was deployed in non-formal schools in particular. JICA supported the non-formal centres through the provision of a comprehensive, accelerated curriculum that was flexible in its nature and geared to targeting overaged children that had missed out on their schooling—providing them with an avenue to catch up and eventually transition into more formal streams. The completion of the accelerated program’s curriculum approximately takes half the time for students relative to the tradition mode of primary schooling. Details in Figure 2.

3.2.2. Local Coordination and Community Mobilisation

Alongside enrolment, there was a grave need to address the shortcomings of the system in place responsible for supporting and overseeing public schools. These institutions have historically struggled to address problems such as teacher absenteeism, low enrolment, high dropout, and poor physical conditions. The reason for this is a lack of resources and underdeveloped monitoring/governance mechanisms—along with the absence of any substantial coordination mechanisms.

This required the establishment of local, grassroots level entities that could act as intermediaries between targeted populations and the governing agencies. Alight’s proposed solution came in the form of school councils, parent-teacher school management committees, village education committees, and other youth groups—thus building upon the work of district education departments. The roles and responsibilities of these intermediary actors were as follows:

- Data collection on OOSC via house visits and consultations with teachers and members of the community to ascertain the quantity and justifications for not attending school.

- Produce village-based report based on the findings of the data—outlining the hurdles/obstacles, a list of schools they can potentially be enrolled in, and the support systems that will need to be in place to make it possible

- Produce village school development plans (SDPs) for each school. These will cover enrolment, retention, and quality of education—identifying targets, responsibilities, deadlines, and strategies.

- Share periodic progress on enrolment numbers, retention status, and implementation of child-tracking system.

Beyond this, these local committees took on the responsibility for special resource mobilisation campaigns under the supervision of Alight’s literacy mobilisers to enhance the range of activities that can be conducted. For this purpose, the literacy mobilisers conducted sensitisation sessions with SMCs/VECs as well as the general public, training sessions of SMCs/VECs in the production of School Development Plans, and played a facilitative role in the implementation of SDPs. This was executed through advocacy campaigns in collaboration with provincial and district-level authorities—taking the form of stakeholder meetings, education marches, celebrations of international/national days, and conducting seminars to highlight schools’ infrastructural needs. A total of 11,716 schools around the country were facilitated in the implementation of SDPs over the course of the initiative, and the improvement of infrastructure of 1,039 government schools was supported (via matching grants) over the course of the project—and the infrastructure of 20 schools was directly enhanced by the efforts of Alight itself. They also played a pivotal role in enrolment drives, education promotion events, the establishment of non-formal schools, and the provision of support/mentoring to teachers.

3.2.3. Capacity Building and Child Tracking

The third objective of the EAC initiative was to strengthen the education management information systems (EMIS) in place and enhance the capacities of the provincial and district level governments while streamlining the coordination mechanisms between them. This was achieved through consultation workshops and rapid capacity assessments of the various departments followed by the development of sectoral plans and recommendations on institutional strengthening. Furthermore, linkages between district level actors, government bodies, international donor agencies and non-governmental organisations were established for purposes of financial and technical support.

Teachers’ training was a crucial part of the EAC initiative—whereby the units responsible for this within the departments of education at provincial and district levels were facilitated in developing learning material based on Child Friendly Education (CFE). These came in the form of workshops and refresher courses, delivered to teachers in both formal as well as non-formal schools in the programme—with the objective of imparting knowledge that would enhance the quality of learning for children in an engaging manner. JICA and Alight collectively took on the role of regularly conducting training sessions for non-formal school teachers on this curriculum to ensure knowledge was being imparted in a streamlined fashion. A total of 4,087 teachers were trained over the course of the initiative, of which 85.4 percent constituted online/remote learning.

Finally, social welfare was placed front and centre of the EAC initiative—taking into consideration the fact that economic barriers are one of the primary reasons for low attendance rates, drop-outs, and a failure to ever join school. This was accomplished by establishing linkages with children in remote districts and offering them scholarships through district and provincial departments. Information about these scholarships, in terms of their eligibility criteria, procedure, and benefits, were imparted to targeted villages to identify the most deserving students. Furthermore, safety nets—in the form of income support—to families were offered in order to minimise/eliminate the opportunity cost for parents in sending their children to school. This was achieved through partnerships with the Pakistan Bait-ul-Maal, provincial education foundations, and the Ehsaas Program’s Waseela-e-Taleem initiative. The WeT programme provided a total of 448,329 students a quarterly stipend over the course of the initiative in order to incentivise them and their parents to continue attending and to counteract the opportunity costs associated with education for families from poorer backgrounds.

3.2.4. Adaptations and Innovations Post-COVID

In order to adapt to restricted mobility as a result of school closures following the onset of COVID-19 and ensure the target of 1,050,000 children was met, Alight initiated a series of new collaborations to leverage the power of technology through online platforms that allowed students to continue their education.

Virtual Teachers’ Training. A first of its kind online platform exclusively for teachers was established in collaboration with the Allama Iqbal Open University and JICA. This allowed teachers to register themselves on a Teachers’ Training Portal (TTP) that they had the freedom to navigate according to their requirements, navigating to the workshops and courses relevant to their particular needs. The platform, which is now one of Asia’s top distance education providers, also allows educators to continue progressing in their professional careers—obtaining formal certifications from the AIOU upon completion of courses. For the purposes of the EAC initiative, modules specifically targeted at non-formal education were developed—covering almost 3,500 individual teachers in total.

Radio School Programme. Students residing in remote areas of Pakistan, such as Gilgit Baltistan, were disproportionately impacted by COVID-19—reason being that not only was mobility restricted, but they also did not have access to fast internet facilities due to the dearth of telecommunications available in the northern areas of the country. Alight responded to this by collaborating with the Ministry of Education and Professional Training to design content for grades 1 to 8 and broadcast them via the national radio to a total of 55 districts, as part of a sub-initiative named the Muallim Knowledge Platform. These modules were based on the Students’ Learning Outcomes (SLOs) of the National Curriculum for English, Urdu, Mathematics, and General Knowledge—and were received with much enthusiasm by the children, so much so that both national and international news organisations produced comprehensive video documentaries on the programme and highlighted its impact on prime time transmissions. They were also uploaded on Alight’s YouTube channel for those with internet access to benefit from.