Understanding Elite Capture

Inarguably, the concept of elite capture is broadly defined along the axis of political economy. Therefore, the articulation of elite capture with inequality, power, extraction, and appropriation is organic, which is also the reason why existing scholarship has focused on building these relationships. There are, however, lacunae when it comes to developing a comprehensive understanding of elite capture. Based on the existing scholarship, this brief entails to unpack elite capture on theoretical and pragmatic levels.

- Who are Elites?

- Dominant groups in terms of economic resources, ethnic background and gender (Tomas, 2005)

- Actors who have disproportionate influence on the development process as well as outcome as a result of their superior social, political or economic status (Post, 2008)

- Distinct social group which enjoys privileged status and exercises decisive control over the organization of the society through official title and/or wealth (DiCaprio, 2012).

- Elite dominate programs where the public good has to be created, implemented and managed by the community.

- Elites have access and control over various structures: economic, social and organizational. The elites belong to the propertied and land-owning class with high levels of income, often from multiple sources. They typically come from the locally dominant caste groups & local families, are placed high in the social hierarchy and belong. They may have a political base and occupy important party positions. They are usually members of civil society associations, and have contacts with prominent politicians, MLAs and MPs.

- Possess large landholdings, traditional positions such as village head or caste leadership; persons having political connections, those who combine power, wealth and prestige, and those having dominant influence on village politics.

These definitions of elites are contextual- the context is embedded in the literature on donor agencies, formal politics, and class and caste analysis. The overarching conceptualization of who an elite is and what on conceptual level, the concept entails, is by Armytage (2020):

‘…the elite is comprised of different power blocs who employ various strategies of competition and collaboration depending on the changing historical and socio-economic circumstances in which they exist.’ (pp. 16)

2. What is Elite Capture?

Defined as a Situation

- The situations, where the elites shape development processes according to their own priorities and/or appropriate development resources for private gain.

Defined as a Process

- The process by which powerful elites skim resources intended for the bottom, and define policies in a way that protects their own interests (Tomas, 2005)

- They corner resources for their own benefit, by corrupt acts, which in the normal course these resources would not have come to them.

How Does Elite Capture Occur?

What does theory say?

- Elite influence comes from their ability to control resources, which have considerable economic value. Their control over productive assets and institutions allows them to influence the allocation of both resources and authority (DiCaprio, 2012)

Empirical Factors

- Greater cohesiveness of interest groups, strengthening the elite networks which results in coopting with the powerful & strengthening alliances

- Voter ignorance at the local level

- The relative extent of electoral competition

- Electoral uncertainty

- The value of campaign funds in local vis-à-vis national elections

- Heterogeneity among local districts with respect to intra-district inequality

- Different electoral systems at the national and local levels

- Greater discurisve control of alternative political ideas and thoughts of locals by the elites.

Sources in South Asia & Africa

- Strategic distortion of local information (informational asymmetry)

- Embezzlement of external resources (resources through donor-induced development projects; community development projects, in particular)

- Complexity of the task perverting participatory process (centralized decision-making)

- The greater homogeneity and cohesiveness among the elite.

- Lack of empowerment and higher levels of ignorance among the poor.

- Expenditure incurred in the elections to local government also contributes to elite capture.

Cases

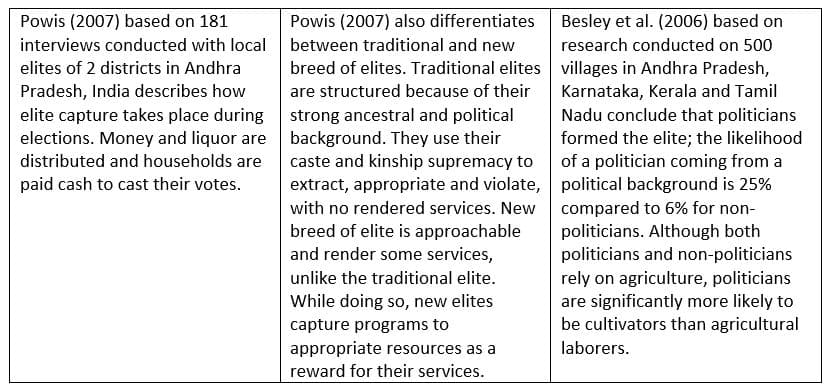

India: Through Formal Elections

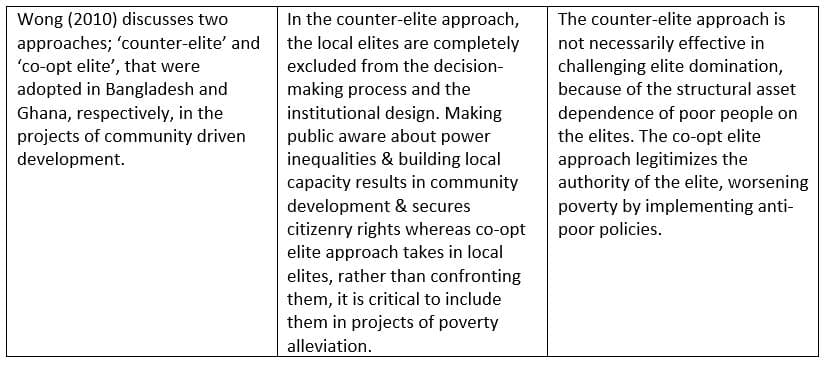

Bangladesh and Ghana: Counter-elite & Co-opt Elite Approaches

4. Outcomes of Elite Capture

Positive Outcomes

Post (2008) documents that for beneficiaries of development projects, elite capture can result in positive outcomes, as pointed out in the following text.

- Beneficiaries express high degrees of satisfaction with projects where decision-making is dominated by elites. There are several reasons for this, stated as:

- Elite involvement in community boards does not impact achieving intended objectives of the projects. It is also observed that in such cases boards function transparently and hence are more inclined towards community participation particularly of women and children.

- Elites can improve community-level projects by contributing expertise and mobilizing resources, but it goes without saying that elites are more likely to obtain projects that matched their preferences than the poor.

- The positive impacts also include increased ownership of communities over projects.

Negative Outcomes

- Elites have control over community decisions and have autonomy to craft rules which discourage community involvement in the development project.

- Due to higher level of inequality in the rural settings, elites have more influence over community decisions and a greater ability to co-opt influential members of the community. This is empirically true for communities which are heterogeneous and have large populations; both factors act as barriers to collective action, and hence such communities are more prone to elite capture.

- In addition to traditional elites, there are development brokers from urban-based NGOs or other organizations who through virtue of their discursive power and co-optation with the traditional elites, can obtain leadership positions at the village level and gain control of development resources. These projects are purposefully initiated before sufficient capacity-building measures are implemented.

- The development projects elites are involved in move forward with implementation before clear rules and processes are established to guide its activities.

5. Quantifying Elite Capture in Pakistan

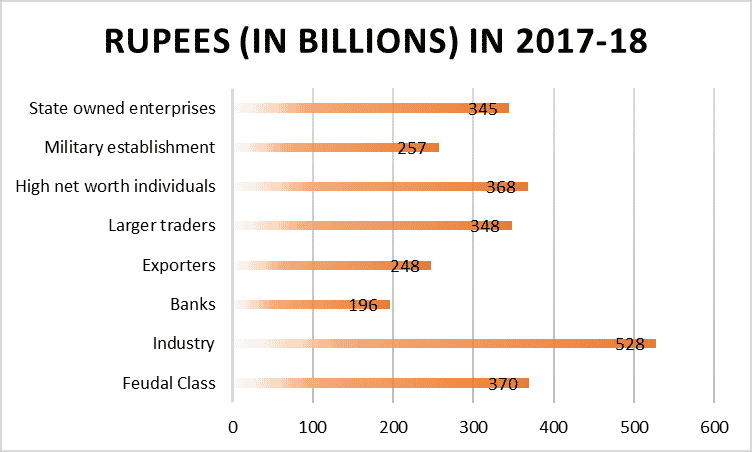

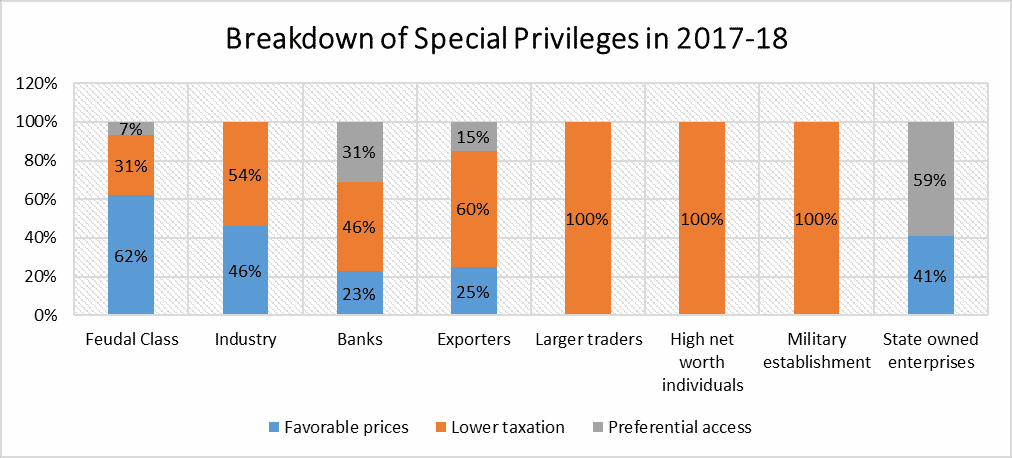

According to UNDP’s Pakistan National Human Development Report of 2020 titled, ‘The three Ps of inequality: Power, People, and Policy,’ a total of eight groups can be identified as having captured the state apparatus – appropriating its resources for largely personal gains. These are state owned enterprises, the military establishment, high net worth individuals (top 1% of earners nationwide), larger traders, exporters, banks, industry, and the feudal class.

In 2017-18, the category titled ‘industry’ was responsible for a total of Rs. 528 billion in losses to the economy – an amount that could have potentially been raised as tax revenues but were instead foregone in the form of the low level of taxation imposed on their activities and incomes, along with the favorable prices they enjoy in the process of selling their commodities. Overall, each of these groupings were – as per the UNDP – responsible for extractions in the range of Rs. 196 billion (banks) and Rs. 528 billion (industry). On average, each was involved in the loss of Rs. 332 billion. Cumulatively, the groups led to losses of approximately Rs. 2.7 trillion for the year 2017-18 – representing almost 8 percent of GDP, a staggering amount. Breakdowns presented in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1

Source: Authors[1]

These figures represent three primary categories: preferential access, lower taxation, and favorable prices. The first refers to the privileged access the groups have to land, capital, and infrastructure/services – owing to their vast networks within and outside of government, which allow them to bypass standard procedures that others must necessarily comply with. Lower taxation can also be divided into three subgroups, i.e., exemptions, evasions, and ineffective rates. Finally, the last category, favorable prices, constitute on the one hand favorable pricing formulas, highly effective protection, and the ease with which cartels/monopolies can operate; and on the other convenient means of accessing cheaper prices for inputs. Breakdowns presented in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2

Source: Authors[2]

_______________________________

[1] Compiled from data from UNDP’s report (2020)

[2] Compiled from data from UNDP’s report (2020)

Furthermore, elite capture does not seem to be extraneous to the government. An analysis of public expenditures, and the benefits that accrue to various income quintiles as a result, may be seen as evidence of this. Social services and subsidies/social protection were distributed in a largely expected manner, i.e., majority concentrated within the 1st to 3rd quintiles. On the other hand, economic services and ‘general’ expenditure illustrated perverse distributions – with over 43.5 percent of benefits accruing purely to the 5th quintile of earners. Cumulatively, 43.3 percent of benefits from public expenditures accrued to this elite class – while only 9.2 percent went to the most vulnerable, i.e., the 1st quintile (UNDP, 2020).

6. Elite Capture: Typologies and Impacts

Figure 3

Source: Borrowed from study by Shapland, Paassen and Almekinders (n.d.)[3]

Shapland, Paassen and Almekinders (n.d) provides an analysis of Scopus research of elite capture as depicted in the figure above. This research is based on the first 100 journal articles about elite capture. The findings classify elites into three typologies: local-level elites, national-level elites and NGOs and Donors. First typology of local-level elites includes village/community elites or local/regional government actors. Second typology of national-level elites includes national government elites and those falling in their domain. Donors as elites are included in the typology based on the post-development critique that development is merely a rhetorical fluff and donors as instruments to fix the economic problems of the developing countries. These donors co-opt with local and international NGOs to not only develop economic policies for the developing countries but also to institutionalize and implement the same. This study highlights that existing literature signifies that for African, Asian and Central and South American countries, the impact of elite capture on bottom-up and community development is problematic as compared to western European countries and North America. 34 studies from Africa, 25 from Asia and 10 from Central and South America substantiates this, as opposed to 2 studies from European countries and North America. Speaking of national-level elites, 10 studies from Global South and 5 studies from Global North articulate the problematic impact of elite capture.

________________________________

[3] Employing the Elite Capture Critique to Legitimize Top-Down Control of Development Resources

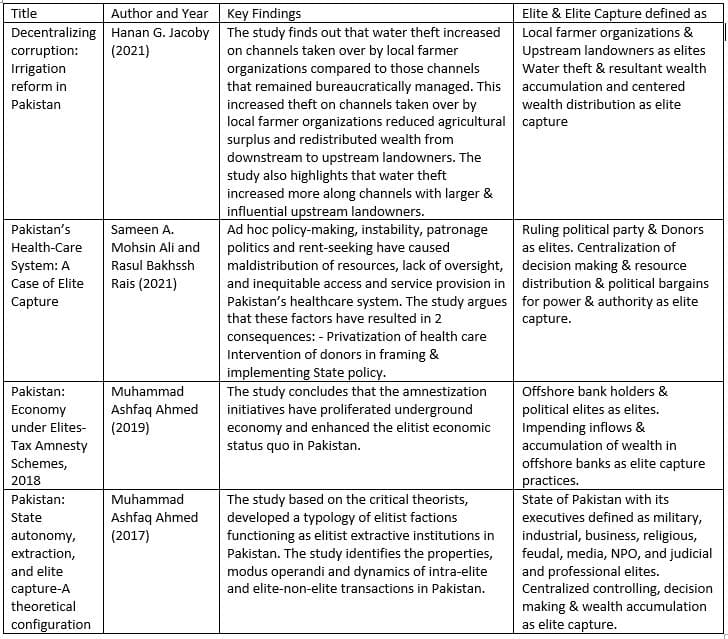

Based on this study’s methodological framework, in the following table is summarized the findings of the journal articles secured from Scopus. The combination of theme which helped in finding relevant academic articles was ‘Elite Capture’ and ‘Pakistan’. A total of 9 articles appeared with this combination. We developed inclusion criteria based on how elite and elite capture are conceptualized in the articles. Based on this criteria, we have included 4 articles; the summary is detailed in the following table.

In addition to these contemporary studies, there are classic texts, for instance:

- Hamza Alavi talks us through civil and military bureaucracy burgeoning into an ‘over-developed State’ and resulting into an underdeveloped country. Alavi (1972) demonstrated that the Marxist analysis of the State needs to be reconsidered and re-conceptualized in post-colonial context. In post-colonial nations, ruling classes are not a monolith, rather composed of several separate classes in connection with the state in distinct ways. The survival of a post-colonial state is also contingent on these disparate ruling classes as both are in direct relationship of receiving and providing reciprocal benefits. Among these ruling classes are included, indigenous bourgeoisie (the owners of industry and business which Armytage (2020) conceptualizes in her ethnography as nevay raje[4]), metropolitan neo-colonial bourgeoisie existent in the form of transnational corporations and the landed class. The state mediates between these three ruling elites to preserve the social order in which the interests of these groups and the state are embedded.

- Asaf Hussain broadens the ambit of elites and includes military elites making Pakistan a praetorian State, bureaucratic elites rendering in services to make Pakistan an administrative State, landowning elites a feudal State, industrial elites a bourgeoisie State, political elites a democratic State and religious elites an Islamic State.

- Ayesha Siddiqa’s concept of Milbus elaborates the internal economy of Pakistan’s military in which military capital is used for military personnel which involves business ventures of 4 welfare foundations, military involvement in toll collection, shopping centres and petrol stations and land and business openings for retired military personnel.

7. Problematizing the Idea of Elite Capture

The idea of elite capture, while useful in highlighting the extent to which resources are extracted from the state by individuals with special privileges owing to their economic, political, and social resources, fails to identify the root cause of this phenomenon. The authors propose that rather than a standalone concept, elite capture be conceived as a symptom of a larger societal level illness – that of weak institutions. This means that the incentive structures that rational agents operating within government agencies respond to are structured in a manner that not only allows but promotes the capture of resources by those in positions of authority. Also known as extractive institutions, these are virtually “designed to extract incomes and wealth from one subset of society to benefit a different subset” (Robinson and Acemoglu, 2012).

In the case of Pakistan (and the larger subcontinent) – a nation the trajectory of which has largely been determined by experiences carrying forward from the colonialism of the British – institutional arrangements fall well within this category. The primary reason for that is that the subcontinent was not a settler colony per se, meaning that the British had little to no incentive to ensure that the fruits of economic growth were funneling down into society at large. Instead, institutions were systematically designed for purposes of extraction – and deployed to fuel the industrial revolution back home (Robinson and Acemoglu, 2012).

________________________________

[4] New landlords.

Donor agencies, for instance, are engaged in a race against time to disburse funds and demonstrate results to their constituencies to preserve credibility. On the other hand,

implementing partners both on the ground and those operating as coordination bodies are pursuing contractual agreements and favorable income for their internal teams – particularly top management. Both these factors function to place efficient allocation of resources on the backburner, whereby a blind eye is turned on potential embezzlement in the form of elite capture in order to ensure projects aren’t derailed. This is particularly the case where democratic governance is not firmly in place, which is especially true across the developing world. When local communities, which are the end-consumers of aid, lack the political leverage to bargain for a higher share of resources from the organization (implementing partner) they are directly dealing with, they tend to accept whatever is being offered to them – as it is still superior to the alternative, i.e., no resources. The incentive for the implementing partner, then, is to minimize – with the approval of the aid agency it is under contract with – the resources attained by the local community, while maximizing its own in the form of salaries and other income (Platteau, 2004). We observe here the way perverse incentive structures create the space within which elite capture can take place – without which it likely would not be possible.

Another salient illustration of the way elite capture takes place is lobbying – a particularly pervasive problem in the developed world. Members of congress, for instance, are known to work closely with big corporations in the pharmaceutical, insurance, and financial sectors and grant them access to special privileges – predominantly in the form of tax breaks and weaker levels of regulation – in exchange for monetary rewards. In strictly legal terms, this is fair game. In fact, it may be argued that a considerable proportion of individuals that make it to those positions in the first place is via financial support from the corporate sector – a favor which, it is expected, will be returned in the future. This is another example of how institutional arrangements are designed to incentivize elite capture – something which, in its current form, is inevitable due to the principles of game theory i.e., refusing to engage will mean a net loss at a personal level.

The authors wish to caution, however, that the discourse around institutional reform in its current form is generally oversimplified. Reform proposals – particularly from international financial institutions – generally come in the form of deregulation, privatization, and the protection of property rights. This troika is advanced in ‘development’ spaces as a panacea of sorts, despite the overwhelming evidence that points to the contrary – salient examples being Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America, where growth plummeted following efforts to introduce GSIs (global standard institutions) to countries in the regions (Chang, 2011). Instead, what is required is to pursue radical democracy down to the lowest rungs of society through grassroots political movements to ensure that policy decisions are representative of the general will – which is naturally responsive to the needs of a given time/space. This will ensure a context specific approach to reform, which is grounded in actual reality rather than abstract theoretical models that are presented as quick fixes.

Naturally, this will also entail a rethinking of culture, tradition, and the general value systems around which society is organized – as these play a pivotal role in shaping institutions via a dynamic, robust, and proactive civil society. In practical terms, this will involve the emphasis on values conducive to growth, such as cooperation, conscientiousness, egalitarianism, a culture based on contractual agreements, the thriving of legal norms, etc. – and the rethinking/reinterpretation of those that are harmful for growth, such as militarism, rigid hierarchism, and hyper-conservatism (Chang, 2011).

One of the central features of discourse around elite capture is that it highlights the fact that local body (devolved) governments are equally as prone to the embezzlement of funds from

elites as at the highest level of government, i.e. provincial and federal – the idea being that power dynamics are no less prevalent at this scale, within communities, divisions, districts, tehsils, etc. If this is true, then the idea of elite capture also functions as a counterargument to devolution of powers – which, in the context of Pakistan, is questionable.

Taken to its logical extreme, this line of argument also then implies that elite capture is a generally ubiquitous phenomenon: which, for purposes of policy making, is not particularly useful. It is, therefore, crucial to avoid adopting a moralizing frame to elite capture – implying that resources are funneled out of the economy due to a failure in the character of the individuals in question, who are, by all measures, simply responding to the incentives presented to them within the organizations or institutions they are operating. It may thus be useful to conceive of the idea of elite capture as possibly being a feature – rather than a bug – of the larger system.

Another pitfall in the discourse surrounding elite capture is the difficulty in attempting to quantify it in precise terms – something that can at best can be based on estimations rather than pure empirical data. This makes sense from a purely logical point of view, as the only reason elites are willing to engage in the capture of state resources is because a) it is difficult to detect, and b) the ease with which they can be exculpated in case of detection – due to weak enforcement of the law as well as the social/economic/political incentives they can offer in return. The generic nature of the numbers on elite capture (which are almost invariably stated as an aggregate figure, e.g. in the UNDP report in the preceding pages) leads to what is known as the tragedy of the commons problem, i.e. that no one individual may be pinned down to take responsibility for the societal pathology in question, leading to each pursuing personal gains in a myopic manner instead.

8. Conclusion

Elite capture takes a variety of forms, including but not limited to rent seeking, politics of patronage, embezzlement of aid funding, and special privileges such as low-income taxes and weak regulatory oversight. All these measures are undoubtedly useful in identifying the way resources are extracted from the economy, which could otherwise have been allocated to productive use.

However, it is crucial to see the concept as a tool for diagnosis rather than an end in itself or a means for highlighting abstract ideas such as moral/ethical decay – which have little to no use value in terms of policy prescriptions. Instead, elite capture ought to be an intermediary step in the quest to correct perverse incentive structures that characterize important institutions – the end goal of which would be to enhance freedoms at the most personal level but to do so in a manner that is oriented towards generating wins for the collective rather than just those at the top.

In its current formulation, the idea of elite capture is advanced in popular discourse to challenge the notion of authority in society – pointing towards special privileges enjoyed by those at the top. The authors suggest this is a mistaken view, as the incentive to strive for excellence ought to always be preserved. This is only possible if the most competent have a clear pathway always open to them to rise to the top and take decisions on behalf of those on lower rungs of the ladder in a manner that is conducive to their needs and aspirations. Therefore, the extent of meritocracy and social mobility should ultimately be the criteria in question. These, of course, are dependent upon the quality of primary institutions that govern society and the pace at which it can generate economic prosperity – which are always in a symbiotic relationship. (Chang, 2011).

After having raised some critical points related to elite capture, we end our discussion by raising as well as responding to a few questions regarding elite capture on conceptual and pragmatic fronts:

- Is elite a monolith?: No, it is not, especially in the context of Pakistan. As detailed in the preceding text that the ruling classes of Pakistan are both time- and space-bound. Alavi articulates three ruling classes as elites (landowners, multinational corporations and industry/business owners), whereas other scholars have broadened the horizon to include bureaucratic and military elites. More contemporary scholarship cites burgeoning upper middle-class and swelling religious groups as part of the elite group. Armytage (2020) classifies elites into established traditionalists in closer ties with the colonial legacies which she calls ‘old money classes’ and navy raje; a brand of new elites (new money classes) which emerged as a response to politico-economic crisis post-1970s. The power struggle between the two is palpable through their socialization practices, alliance with other ruling classes of military, formal politics, bureaucracy, and donor agencies. Hence, elites constitute a differentiated mass and must be conceptualized as a polylith.

- What do elites capture?: Capital. More assertively, economic capital. But literature also cites that the intent to capture is not entirely driven by economic reasons or the end is not always to get hold of economic resources. There are multiple forms of capital functional to coopt and create alliances among elites, such as social capital, cultural capital and political capital. The aim is to operationalize these capitals to gain symbolic capital (the unquestioned and unchallenged respect and subservience by the people at large to the ruling elite group; the case in point being the dynast politicians and the political parties impinging upon religious ethos).

- How do elites capture?: Differentiated; along the axis of social networking, using existing vote bank, capitalizing on symbolic capital and existing coalitions, laddering up powerful in-groups, and creating new alliances.

- Is elite capture an issue?: The classic and contemporary scholarship reverberates that elite capture leads towards expropriation and extraction of human and economic resources. Considering social heterogeneity in the world we live in, differences among people are marked by differential access and command over economic resources, including land and capital. As a response to which, an elite class/social group emerges. The critical point is to analyze if this elitist class captures and creates disproportionate inequalities through formalizing extractive institutions. The question is of whether inclusive or extractive institutions are being upheld or institutionalized by these groups/classes.

- Is elite capture a rhetoric?: Yes. Elite capture as a concept is conceptually a rhetorical fluff. Elites exist, they capture socio-economic and politico-economic spaces and create relationships of dependency between them and the powerless, but in academia a granular understanding of what it entails, is under-explored. The concept is often articulated in academic domains, policy circles and public discourses as an escapist strategy in an attempt to not clearly articulate who are the elites in Pakistan? What is their modus operandi? What is the intent and what can be consequences? The concept will remain a rhetorical fluff unless these questions are asked and responded with research.

References

Ahmed, Muhammad Ashfaq. (2017). Pakistan: State Autonomy, extraction and elite capture- A theoretical configuration. Pakistan Development Review, 56:2, 127-162.

Ahmed, Muhammad Ashfaq. (2019). Pakistan: Economy under elites- Tax amnesty schemes, 2018. Asian Journal of Law and Economics, 10: 2, 2019-0016.

Alavi, Hamza. (1972) The State in post-colonial societies: Pakistan and Bangladesh. New Left Review.

Armytage, Rosita. (2020). Big capital in an unequal world: The micropolitics of wealth in Pakistan. Berghahn Dislocations. New York; Oxford.

Besley, Timothy, Rohini Pande and Vijayendra Rao (2006). The Political Economy of Grama Panchayats in South India, in GopalKKadekodi, RaviKanbur and Vijayendra Rao (eds.) Governance and Development In Karnataka,Working Paper XX, Department of Applied Economics and Management, Cornell University, New York, USA

Chang, H. J. (2011). Institutions and economic development: theory, policy and history. Journal of institutional economics, 7(4), 473-498. Development How to Series, Vol. 3, February. Development Papers, Paper No. 109, December, The World Bank.

DiCaprio, Alisa (2012). Introduction: The Role of Elites in Economic Development. In Amsden, Alice H., DiCaprio, Alisa and Robinson, James, A. (Eds) The Role of Elites in Economic Development, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Jacoby, Hanan., Mansuri, Ghazala. And Fatima, Freeha. (2021). Decentralizing corruption: Irrigation reform in Pakistan. Journal of Public Economics, 202.

Hussain, Asaf. (1976). Elites and political development in Pakistan. The Developing Economies, 14:3, 224-38.

Mohsin Ali. Sameen A. and Rais, Rasul Bakhsh. (2021). Pakistan’s health-care system: A case of elite capture. South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 44:6, 1206-1228.

Pakistan National Human Development Report 2020. The three Ps of inequality: Power, people and policy. United Nations Development Programme.

Platteau, Jean-Philippe. (2004). Monitoring elite capture in community-driven development. Development and Change, 35: 2, 223-46.

Post, David (2008). CDD and Elite Capture: Reframing the Conversation, World Bank

Powis, Benjamin (2007). Systems of Capture: Reassessing the Threat of Local Elites, Social

Robinson, J. A., & Acemoglu, D. (2012). Why nations fail: The origins of power, prosperity and poverty (pp. 45-47). London: Profile.

Tomas, Amparo (2005). A Human Rights Approach to Development.

Wong, Sam (2010). Elite Capture or Capture Elites? Lessons from the ‘Counter-elite’ and ‘Co-optelite’ Approaches in Bangladesh and Ghana. Working Paper No. 82, UNU World Institute for Development Economics Research, Finland.