Beyond Import Substitution: Charting Pakistan’s Future with Export-led Growth!

In the expansive arena of economic governance, Ludwig von Mises’ profound assertion resonates: “If one rejects laissez-faire on account of man’s fallibility and moral weakness, one must, for the same reason, also reject every kind of government action.” Amidst this philosophical backdrop, Pakistan grapples with a complex array of economic challenges, demanding a sophisticated and nuanced approach to trade policies.

A disconcerting array of economic indicators paints a grim picture. Over the past five years, the budget deficit has ballooned from 5.8% to a concerning 7.7% of the GDP. The tax-to-GDP ratio has witnessed a precipitous drop from 11.4% to 9.2%, accompanied by a sharp decline in development spending from 4.1% to 2.3%. Public debt, a looming spectre, now constitutes a formidable 74.3% of the GDP. Stark income inequality persists, with the top 10% commandeering 44% of the national income, while the bottom 50% languishes with a mere 16%, resulting in a glaring per capita income ratio of 14:1. In official records, the unemployment rate has risen significantly, climbing from 6.9% in 2018-19 to a concerning 9.5% in 2022-23, affecting more than 7 million workers. Unofficial figures, however, paint a grimmer picture, indicating that the actual unemployment rate may surpass 20%.

Poverty, estimated at 34% in 2018-19, is projected to reach a staggering 46% by 2022-23, affecting over 20 million idle youth. This crisis is further exacerbated by a real wages slump of over 20% in the last two years. The tax burden, distributed unevenly across sectors, contributes to an overall tax incidence of under 10% of the GDP, with a UNDP report suggesting elite capture causing a loss of over 2.5% of the GDP.

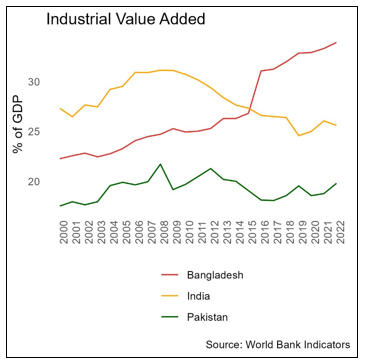

The industrial contribution to the economy is currently very low, and it has experienced a decline in recent years, with strong indications pointing towards widespread deindustrialisation across the economy.

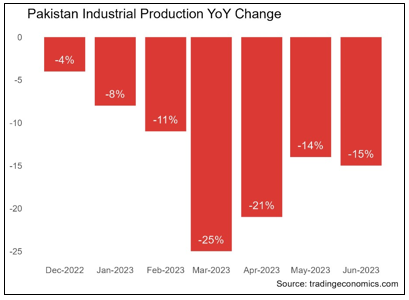

The contraction of industrial production during the 2022-23 economic crisis, intensified by economic volatility, escalating energy costs, inflation, and exchange rate depreciation, has precipitated the permanent closure of numerous firms. This impact is particularly pronounced in the textile and apparel sector, evident in a significant year-on-year decline in power consumption for firms on both LESCO and MEPCO networks. These challenges accentuate the pressing need for Pakistan to embrace an export-centric culture, a pivotal shift considering the country’s gross external financing requirements, which are poised to exceed $25 billion annually for the next five years.

Protectionism, as a set of policies aimed at shielding domestic industries from foreign competition through tools like tariffs, quotas, subsidies and non-tariff barriers, is a focal point of discussion. However, the pervasive call for import substitution as a solution to the ongoing economic crisis reveals a fundamental misunderstanding. The crux lies in the basic premise of international trade, founded on the principle of comparative advantage. In a simplified two-goods-two-economy scenario, each economy optimally produces and exports what it excels at, extending this principle to the diverse goods and economies in the real world.

Economies, as a rule, should export what they excel in producing and import what they lack comparative advantage in. The current discourse in Pakistan, advocating for benefits to ‘import substitution’ industries to reduce imports and enhance the Balance of Payments (BoP), is flawed. Import substitution is inherently unproductive and internationally uncompetitive. Granting benefits and protection to these industries perpetuates inefficient production, leading to elevated prices for domestic consumers and wasteful resource utilisation. The genuine solution lies in fostering export-led growth, where all industries orient towards exports, bolstering foreign earnings to offset the impact of imports and maximising economic advantages.

In this strategy, the focus should narrow down to a few key sectors where the economy boasts a comparative advantage. Simultaneously, efforts should concentrate on creating localised backward and forward linkages within these sectors. This approach stands in stark contrast to the impractical noon of attempting to localise the production of an exhaustive range of goods under the umbrella of ‘import substitution’.

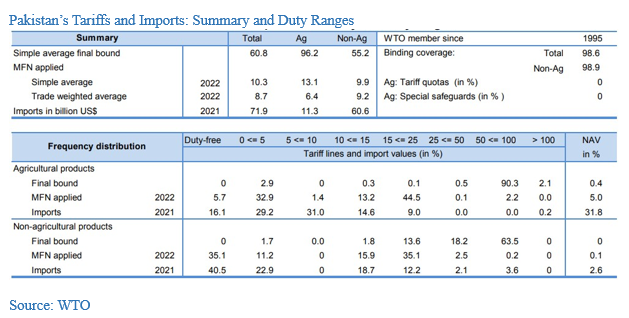

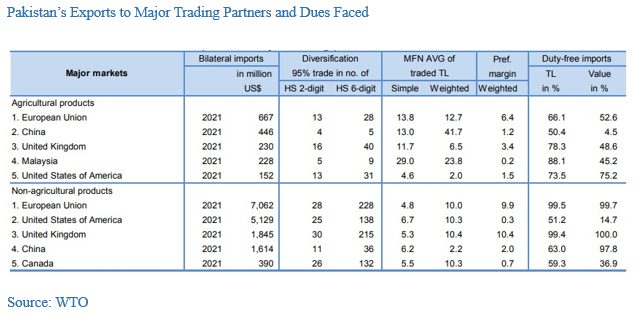

In 2022, Pakistan’s trade policies exhibit a subtle yet complex stance on tariffs, with an exceptionally high applied tariff rate of 98.6% (see table below). According to the WTO’s World Tariff Profile 2023, this rate underscores the challenges and potential adverse consequences of protectionist measures. Such a high applied tariff rate can act as a significant trade barrier, leading to increased costs for imported goods. This, in turn, may have detrimental effects on consumers, businesses, and the overall efficiency of the economy. The focus on applied rates in this analysis aims to shed light on the immediate and tangible impacts of protectionist trade policies. Particularly, the agricultural sector faces comparatively higher tariffs with a simple average applied rate of 10.3%, while non-agricultural products face a rate of 13.1%. Trade-weighted averages for agricultural (8.7%) and non-agricultural (6.4%) goods further highlight variations within different product categories.

Examining specific product groups, the tariff analysis unveils limited duty-free imports and a prevalence of applied tariffs falling within the 15% to 25% range, parcularly for non-agricultural products. Disnct variaons emerge among product categories, with higher average duty rates for non-electrical and electrical machinery, in contrast to lower rates for petroleum and chemicals. Major trading partners for both agricultural and non-agricultural products include the European Union, China, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

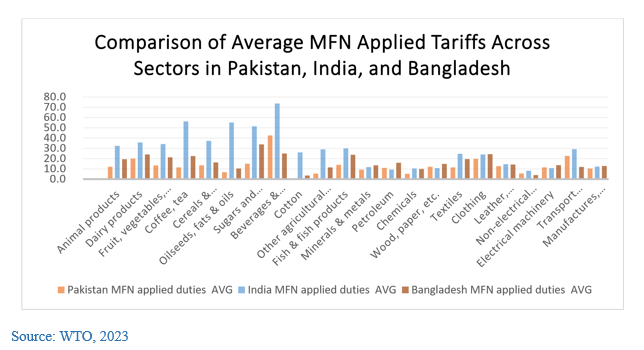

The analysis of Most Favored Nation (MFN) applied to Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh sheds light on the implications of protectionist measures on the Pakistani economy. While Pakistan generally maintains lower average dues, indicative of a relatively open trade policy, the impact of protectionism extends beyond duty rates to encompass non-tariff barriers and subsidies. Striking a balance is crucial; lower dues in sectors where Pakistan has a comparative advantage, such as cotton, suggest the potential benefits of an open trade approach. However, protectionist measures, if not carefully calibrated, could lead to inefficiencies, reduced competitiveness, and missed opportunities in global markets. The key lies in fostering an environment conducive to export-led growth, protecting domestic industries judiciously, and ensuring overall economic efficiency for sustained growth.

Debates are useless without factual concepts, and to begin with, Pakistan’s economy has not been performing well. Foreign exchange reserves started at $4.5 billion at the beginning of the current financial year, and the national currency, the rupee, depreciated by over 81% in the last two years. External debt stands at nearly $128 billion, constituting almost 43% of the GDP. Cumulative external financing requirements, net of likely rollovers, are projected to exceed $55 billion from 2023-24 to 2025-26.

The World Bank, in its 2023 feature story titled, “Protectionism Is Failing to Achieve Its Goals and Threatens the Future of Critical Industries”, expresses heightened concerns regarding the repercussions of protectionism on global trade. Despite escalating trade tensions and geopolitical challenges, global trade showcases remarkable resilience, an observation that gains significance as protectionist measures become more prevalent, prompting discussions about deglobalisation. This evolving landscape unveils three distinct paradoxes in global trade, each with implications that resonate with Pakistan’s economic context:

I. China’s increased centrality amid the U.S.-China trade war

Notably, despite the tumultuous trade relations and conflicts between the United States and China, China’s centrality in global trade networks has strengthened. The paradox lies in the fact that geopolitical tensions have not diminished China’s pivotal role in the global trade landscape. In the context of Pakistan, intricately linked with China through initiatives like the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), this paradox suggests that strategic partnerships with influential trade partners can flourish, even in the face of protectionist measures.

II. The growing significance of global value chains:

Contrary to expectations, disruptions such as the U.S.-China trade war and the COVID-19 pandemic have failed to weaken global value chains. Instead, these chains have increased in significance, challenging predictions and underlining their enduring importance in global trade. For Pakistan, actively participating in global value chains, especially in sectors like textiles, becomes even more crucial as the paradox emphasises the continues integration and relevance of these chains in the face of protectionist headwinds.

III. Firms persist in global connections despite challenges

The paradox of firms maintaining global ties amid challenges like trade tensions and disruptions underscores the resilience and persistence of global business connections. This resilience is particularly relevant for Pakistani businesses that face similar challenges. Instead of retracting to regional or local interactions, businesses in Pakistan can draw inspiration from this paradox, emphasising the importance of maintaining and expanding global ties with customers and suppliers despite obstacles posed by protectionist measures.

These paradoxes underscore the dynamic nature of global trade in the context of protectionism and highlight potential strategies for Pakistan to navigate these challenges. Increased international openness and cooperation would better achieve the goals currently pursued through protectionist measures.

The World Bank also emphasizes the need for a new consensus on global rules to address international tensions and benefit all countries. The problem is not excessive globalisation but excessively narrow regulation, advocating for a global set of rules covering various aspects beyond trade.

Recognising the failure of protectionism and import substitution approaches, the emphasis on export-led growth becomes imperative. The need to increase foreign exchange earnings is highlighted as an alternative to falling deeper into the debt trap. Fostering an open and competitive international trade environment is essential for stabilising industries, encouraging growth, and creating opportunities for market diversification. Free trade, by fostering global economic cooperation, can mitigate the impact of economic downturns on individual countries by providing opportunities for market diversification, access to resources, and the possibility of stabilising industries through increased exports and market competitiveness.

But does trade liberalisation raise economic growth in developing countries, such as Pakistan, and if it does, why? To answer this, it is important to understand the relationship between trade liberalisaon and economic growth in developing countries. Proponents assert that removing trade barriers enhances efficiency, expands markets, facilitates technological transfer, and fosters competition, all contributing to economic growth. The theoretical foundation lies in models like endogenous growth theory, emphasising the positive impact of international trade. However, critics argue that benefits may be unevenly distributed, and success depends on factors such as domestic policies and institutional readiness.

The economic literature provides diverse empirical evidence on the impact of trade openness on economic growth, emphasising various mechanisms. Scholars like Kruger (1978) argue that trade liberalisation encourages specialisation in industries with economies of scale, improving efficiency and productivity in the long term. Taylor (1981) finds that a growth in manufacturing exports stimulates technological progress, enhancing absorptive capacity and ultimately raising industrial and economic growth. Robinson (1991) suggests that export growth boosts total factor productivity by increasing competitiveness and economies of scale, while imports growth may hinder productivity. Barro and Martin (1995) posit that trade openness contributes to economic growth by importing technical knowledge and benefitting from foreign direct investments and innovation spillover effects. Romer (1990) associates trade openness with industrial growth, asserting that it facilitates the adoption of a wide range of innovations, prompting a shift from raw material to manufactured goods. Chamberlin (2014) contends that human capital formation positively influences the effect of trade openness on economic and industrial growth, with optimal levels of trade liberalisaon. Dollar and Karray (2003) suggest that more open economies with better institutions develop faster. Vallumea (1994) emphasises the positive effects of public policies, openness, and investment in human capital on industrial output and export promotion. Ahmad (1999) explores the behaviour of trade liberalisation and investment in human capital, finding positive contributions to industrial growth and overall economic expansion. The findings of the literature indicate the significance and necessity for developing nations to undertake extensive trade liberalisaon initiatives to foster and maintain economic growth effectively.

Case Study 1: Tariffs on Polyester Staple Fibre in Textile Industry

Pakistan’s textile industry, historically a significant contributor to the economy, has faced challenges, witnessing a decline in contribution and employment trends. The economic crisis in 2022-23, marked by high volatility, rising energy costs, and exchange rate depreciation, led to the closure of several textile firms, with a substantial decrease in power consumption across the sector.

Export-led growth is crucial for Pakistan, evident from the failure of protectionism and import substitution strategies. The imposition of tariffs and protectionist measures on polyester staple fibre (PSF) in Pakistan has adversely affected the textile industry, impeding its global competitiveness. Despite the increasing global demand for synthetic fibres, particularly polyester, Pakistan’s textile industry has been slow to shift from conventional cotton, liming its share in the expanding market for synthetic textiles. Garment exports all favor cotton at an 80:20 ratio, with only a quarter of spinning machines utilising man-made fibres.

Moreover, the concentration of global polyester staple fibre production in countries like China, India, and Southeast Asia, which dominate synthetic textile exports, highlights Pakistan’s limited participation in the MMF (man-made fibre) apparel market. Protectionist policies and the absence of a fully integrated chemical industry for synthetic polymers hinder Pakistan’s progress in this sector. Adequate raw material availability could have boosted the country’s share in the global synthetic textiles market, but domestic policies influenced by protectionist measures have impeded tapping into this potential.

To boost Pakistan’s textile industry, the 12% custom duty on Polyester Filament Yarn (PFY) should also be eliminated, ensuring no import duty on this crucial raw material. Aligning withholding tax (WHT) and abolishing the 3% value addition tax (VAT) at the import stage for PFY is vital. The current policy, with total import dues reaching 20%, including antidumping duty, hampers PFY industry growth and raises costs for end-users. Additional Regulatory Duty exacerbates challenges, underscoring concerns about protectionist measures impacting the textile sector. Creating a competitive and open market is essential for the industry’s success.

On the other hand, to enhance its global competitiveness, Pakistani manufacturers must build industry capacity for producing textile articles based on man-made fibres, recognising the growing demand in the global market for synthetic or man-made fibres (MMF) over traditional cotton articles. While the input is duty-free for qualifying firms under certain schemes, a significant 80% fail to meet the criteria. However, these non-qualifying firms, despite lacking duty exemptions, play a crucial role as technology capacity incubators, especially in the absence of Polyester Staple Fibre (PSF), fostering cultural development. Unfortunately, Pakistan has struggled to fully leverage benefits from initiatives like GSP+ due to an economy heavily reliant on textiles and a lack of awareness and interest among traders, impeding the country’s ability to exploit the full advantages of such programs. It is also to be noted that Pakistan misses out on around 70-80% of the export lines to Europe where the MMF is heavily concentrated, indicating a lack of full utilisation of GSP+ benefits.

Case Study 2: Protectionism in Agriculture

Protectionist policies in Pakistan’s agriculture sector, intended to bolster local farmers and ensure food security, have faced limitations in achieving their goals. Contrary to expectations, the academic text indicates that the gains from agricultural trade liberalization surpass those from protectionism. Many studies, such as the one conducted by Ahmad, Khan, and Mustafa (2022), suggests that protectionist measures have not significantly benefited Pakistani farmers, with richer rural households reaping more substantial rewards under trade liberalisation. Concerns about income distribution amongst vulnerable populations, particularly poor rural households, have arisen, challenging the assumption that protectionism leads to improved food security.

The challenge of improving productivity in Pakistan’s agricultural sector is intricately linked to the issue of protectionism. The sector has been marked by stagnation in output per worker for three decades, partly due to state interventions that created distortions favouring major crops like cotton, sugarcane, wheat, and rice. These interventions have disproportionately benefited large landowners and banks at the expense of small farmers, consumers, and future generations. The heavy subsidies and regulations in the agricultural sector, aimed at addressing policy concerns, have often resulted in unintended consequences. For instance, wheat procurement programs with fixed support prices introduce allocative distortions, reducing productivity and leading to oversupply, which primarily benefits large farmers and banks. Similarly, sugarcane, reliant on underpriced water and other subsidies, requires minimum support prices for financial viability. These protectionist measures have hindered diversification, distorted public resources, and resisted market reforms that could drive technological change. Addressing protectionism and fostering competition is crucial to unlocking the true potential of Pakistan’s agricultural sector, as seen in the stark productivity difference between Punjab in Pakistan and Indian Punjab. Breaking away from protectionist policies and embracing innovation can lead to significant gains in GDP and overall economic development.

Moreover, the implications of protectionism extend to international trade relationships. While protectionist measures aim to shield domestic agriculture, many studies such as the one conducted by Ahmad, Khan, and Mustafa (2022), point out that exposing the sector to foreign competition through liberalisation may result in concerns about market access and potential losses for less-developed countries. The broader economic impact is underscored by the conflict among empirical studies regarding gains from agricultural trade. Despite marginal economic growth, protectionist policies in Pakistan have not effectively addressed income inequality as they often benefit select industries and contribute to higher prices, disproportionately impacting lower-income individuals and hindering overall economic growth and job creation, emphasising the need for a distinct approach that considers welfare, income distribution, and global trade dynamics when evaluating the efficacy of trade policies in the agriculture sector.

Insights from both case studies affirm the documented inefficiencies stemming from protectionism, particularly in sectors such as agriculture, automobiles, polyester staple fibre, and glass. The textile industry, cornerstone of Pakistan’s economy, faces decline amid economic challenges, highlighting the imperative shift towards an export-centric approach. While Case Study 1 extols the benefits of free trade for sectors like textiles, Case Study 2 underscores the limitations of protectionist policies in agriculture, revealing that trade liberalisation offers more significant gains than protectionism, especially for poorer rural households. The broader implications on income distribution and international trade relationships emphasise the need for subtle yet effective approaches that consider welfare, income equality, and global trade dynamics in evaluating the efficacy of trade policies in these critical sectors.

The authors are affiliated with the All-Pakistan Textile Mills Association (APTMA).

References

- Ahmad, S., Khan, M. A., & Mustafa, U. (2022). Agricultural Trade and Ultra-Poor in Pakistan: An Application of CGE Model. Millennial Asia, 13(3), 491-512. htps://doi.org/10.1177/09763996211010607

- Barro, R., & Martin, S.-i. (1995). Technological Diffusion; Convergence and Growth. CEPR Discussion Paper.

- Chamberlin, E. (2014). Scenario of International Trade Openness and Export Growth. Peer Review of Internaonal Economics.

- Competition Commission of Pakistan (2011) Competition Impact Assessment Report On Polyester Staple Fibre Industry of Pakistan. Available at: htps://cc.gov.pk/assets/images/Downloads/assessment_studies/compeon_impact_a ssessment_report1.pdf (Accessed: 11 December 2023).

- Dollar, D., & Karray, A. (2003). Institutions, Trade, and Growth. Journal of Monetary Economics.

- Ellahi, N., & Mehmood, D. H. (Year not provided). Analyzing Empirical Relationship between Trade Openness, Industrial Value Added, and Economic Growth.

- Freedom Foundation. (n.d.). Pakistan’s Challenges: Political Stability and Economic Revival. Retrieved from htps://www.freiheit.org/pakistan/pakistans-challenges-policalstability-and-economic-revival

- Hussain, S. S., & Ahmed, V. (2012, July). Experiments with Industrial policy: The Case of Pakistan. Sustainable Development Policy Institute; Working Paper No 124; 2012. Retrieved from htp://arks.princeton.edu/ark:/88435/dsp01sf2687480

- Kruger, O. A. (1978). Foreign Trade Regimes and Economic Development: Liberalizaon attempts and consequences. Ballinger.

- Muhammad, S. (2012). Does trade openness affect long-run Growth? Cointegration, causality, and forecast error Variance Decomposition Test for Pakistan. Munich Personal RePEc Archive.

- Pakistan Business Council. (n.d.). Potential for a Pakistan – U.S. Free Trade Agreement. Retrieved from htps://www.pbc.org.pk/research/potenal-for-a-pakistan-us-free-tradeagreement/

- Robinson, J. (1991). International trade with Endogenous Growth. European Economic Review.

- Romer, D. (1990). The problem of Development. Journal of Political Economy.

- Siddique, A. H., & Iqbaal, J. (April, 2005). Impact of Trade Openness on Output Growth for Pakistan: An Empirical Investigation. Munich Personal RePEc Archive.

- State Bank of Pakistan. (n.d.). Third Quarterly Report FY18. Retrieved from htps://www.sbp.org.pk/reports/quarterly/fy18/Third/SpecialSecon–pdf

- Taylor, W. J. (1981). Growth and exports Expansion in Developing Economies: Some Empirical Evidences. Journal of Development Economics.

- Vallumea, D. (1994). Openness, Human Development, and Fiscal Policies: Effects of Economic Growth and Speed of Adjustments. IMF Staff Paper.

- World Bank. (2022). From Swimming in Sand to High and Sustainable Growth: A roadmap to reduce distortions in the allocation of resources and talent in the Pakistani economy. Pakistan’s Country Economic Memorandum 2022. Retrieved from htps://doi.org/10.1596/38133

- World Bank. (2023, August 29). Protectionism Is Failing to Achieve Its Goals and Threatens the Future of Critical Industries. Feature Story. Retrieved from htps://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2023/08/29/proteconism-is-failing-toachieve-its-goals-and-threatens-the-future-of-crical-industries

- World Trade Organization, International Trade Centre, & UNCTAD. (2023). World Tariff Profiles 2023. Retrieved from wto.org/stascs ISBN 978-92-870-7402-7 (print) ISBN 978-92-870-7401-0 (pdf)