Climate justice: relief, rebuilding, and reparations

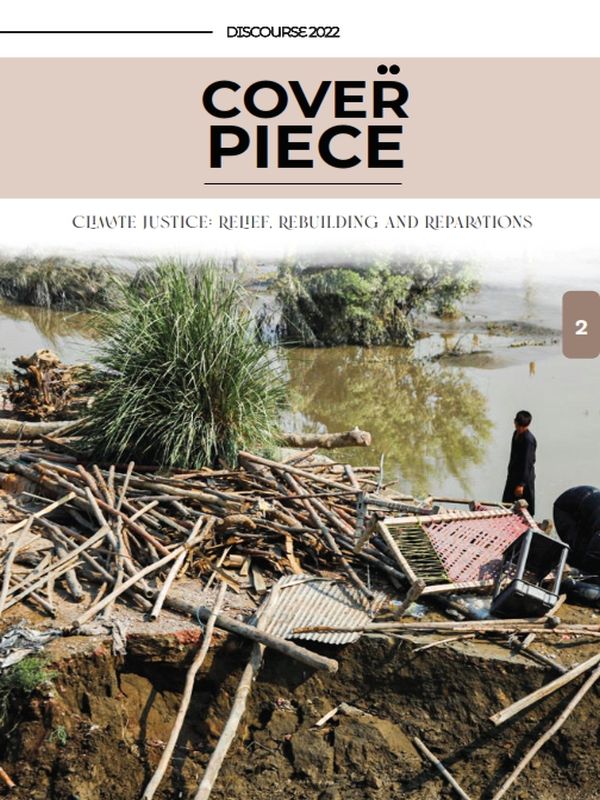

Over the course of the past 6 months, Pakistan has experienced floods the likes of which have rarely – if ever – been seen before in the nation’s history. As per Relief International, a minimum of 33 million people have been displaced, 6.4 million people are in need of humanitarian assistance, 1.7 million houses have either been damaged or destroyed entirely, 634, 749 people have been displaced, and 1,355 lives have been lost. The most seriously affected regions have been Sindh, Balochistan, Punjab, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and Gilgit-Baltistan – in that order. This is not to mention the spill-over effects that have come in the form of landslides, rampant disease, rising rates of mental illnesses, and at the broadest level economic shocks that have left entire communities unable to access food, water, shelter, and basic amenities.

With little to no support from the state apparatus, a bottom-up mobilization of civil society has been observed – whereby non-government organizations and community based organizations have crowdfunded a relief effort, and while this has proven a godsend in incredibly tumultuous and uncertain times, these efforts have lacked a central coordination mechanism that can ensure optimal resource allocation to all areas depending on need. This, of course, is due to the absence of free information that could describe the severity of the situation down to at least the district level, thus leading to a fragmented and largely improvisational approach to disaster response.

From setting up medical camps and temporary encampments for families to having essential supplies such as water, rations, medicine, and bed nets, it is clear that civil society has led efforts for relief – leveraging the media (print, television, and online) to raise funds to support activities. Some organizations have even chosen to make direct transfers to vulnerable families, whereby a monthly stipend ranging from Rs. 5,000 to 10,000 has been allocated following a basic needs assessment. This is to ensure efficiency and ensure that those receiving funds may spend them according to their specific requirements rather than adopting a one-shoe-fit-all approach.

Countless roads, bridges, phone lines, electricity sources, and household assets have been completely decimated over the course of the past few months. On the other hand, a variety of crucial crops – including cotton, maize, sugarcane – as well as livestock, fisheries, and forestry also suffered huge damages: which will inevitably impact several sectors. This will naturally lead to dwindling exports, in which cotton plays a central role due to its use in the textile industry, and contribute to further inflation in the country: disproportionately impacting the most economically vulnerable segments of Pakistan’s population.

According to the Ministry of Finance, total damages in each of the provinces are: Rs. 7 billion in AJK, Rs. 53 billion in Balochistan, Rs. 6 billion in FATA, Rs. 93 billion in/around Islamabad, Rs. 4 billion in Gilgit-Baltistan, Rs. 100 billion in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Rs. 219 billion in Punjab, and Rs. 373 billion in Sindh. The biggest losses in terms of sectors were incurred in agriculture (Rs. 429 billion), housing (Rs. 135 billion), and transport/communication (Rs. 113 billion). Experts at the Ministry claim reconstruction costs for these losses will amount to approximately Rs. 578 billion – or USD 2.66 billion. This is not accounting for economic shocks that are likely to be seen, which will inevitably multiply total costs.

These developments have kick-started national (and global) conversations on climate justice vis-à-vis ‘reparations’ – whereby the developed world has come under diplomatic pressure to compensate countries that are paying the price for global warming and climate change more broadly as a direct consequence of its share in global carbon emissions. Jason Hickel, economic anthropologist and professor at the Autonomous University of Barcelona, has quantified the extent of the disparity in this arena. According to his research, the USA alone accounts for around 40% of ‘overshoots’ (carbon emissions above fair share, accounted for population) – and the Global North, i.e. USA, Canada, Europe, Israel, Australia, New Zealand, and Japan, cumulatively account for a whopping 92% of overshoots. This suggests that exclusively focusing policy attention on the domestic arena, in the form of ‘climate resilience’ is likely to be a failing strategy. Subsequent governments in Pakistan, particularly the foreign and climate change ministries, would do well to adopt an orientation that takes these facts into account, pushing for debt relief not as ‘aid’ or ‘charity’ but justice. Foreign Minister Bilawal Bhutto Zardari has, over the course of the past couple of months, main inroads in this arena and voiced a clear, unapologetic demand for these: something that Pakistan ought to persevere on.

Globally, the threat of climate change looms large – threatening to wipe entire ecosystems and render large parts of the planet uninhabitable as early as 2050. International organizations, including international financial institutions and multilateral donor agencies, must therefore come together to not only focus on mitigation efforts in the developing world but also push industrialized nations to strictly curtail the fossil fuel industry: in which just 100 companies are responsible for over 70% of global emissions since 1988 as per a study by Carbon Majors. At a broader level, academia and knowledge production must challenge the neoliberal ideology of unfettered growth (for its own sake) – in which the private sector is granted a free hand in damaging the environmental commons, exploiting the working class, and influencing public policy.

Indeed, income inequality has steadily increased across the globe since the onset of the ‘privatize, liberalise, and deregulate’ mantra of the Washington Consensus. According to Oxfam International, the top 1% of earners have captured 20 times more global wealth than the bottom 50% since 1995 and the richest 20 people in the world are polluting a whopping 8,000 times more carbon than the billion poorest. Framing these statistics as anything other than a vicious form of structural violence against vulnerable communities is a mistake: and a careful review of policy orientations since at least 1980 is in order, one which dispenses with failed textbook approaches to developments and replaces them with rigorous, nuanced, context-specific orientations that treat the ‘economy’ as an amalgam of social, cultural, political, psychological, etc. forces rather than merely commercial activity, seen in isolation.

We hope this issue of the newly restructured Discourse magazine, in which we opened up submissions from the general public and added several new sections – including Business, Opinion, Sport, History, and Arts & Culture – offers useful insights on the developing situation and sparks debates among academics, policy analysts, governments, and corporate/development sector professionals on how we may go about addressing the recent floods. Our overarching theme for this issue is thus Climate Justice, with subthemes of relief, rebuilding, and reparations.

Thank you for reading: keep the discourse alive!

Sincerely,

Editorial Board

Discourse Magazine

Pakistan Institute of Development Economics