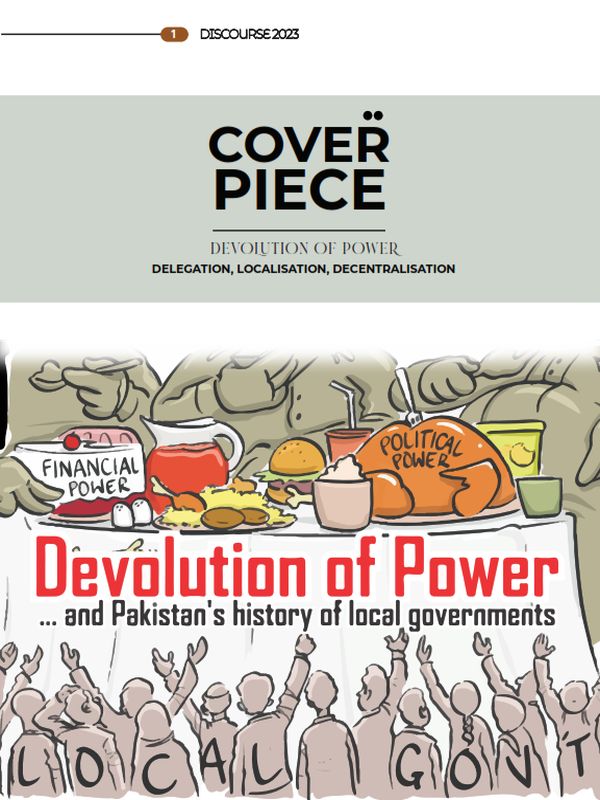

COVER PIECE (Discourse 2023-04)

Pakistan’s institutional arrangements have remained largely intact since independence – carrying forward the colonial legacy of excessive centralisation. During the British Raj, this made sense as the primary objective was not the pursuit of inclusive, sustainable growth and development but rather extraction. This is when resources, particularly raw materials, were coercively funnelled back home to fuel the industrialisation process. In order to ensure this, ordinary citizens had to systematically be obstructed from all decision making processes in the governance domain.

The only ‘role’ a select few of them – the ‘brown sahibs’ – had was to act as facilitators, manufacturing consent for the wishes of the administration and getting the legwork done when it came to executing tasks. While terrible for the indigenous populations, this structure of power worked incredibly efficiently for the rulers: who were able to extract an estimated USD 45 trillion from the subcontinent during the period 1765 to 1938. This legacy has meant deeply entrenched structures of governance that have, to this day, not been revised or thought about in a critical and democratic manner.

On this, there are various lessons Pakistan may learn from other countries across the globe that have – through a gradual evolutionary process – managed to instil institutional arrangements that are dynamic, efficient, and participatory. These include the likes of China, France, the United Kingdom and the United States. For example, just the city of London has a two-tier local government system – one executive/legislative and one administrative – that is in charge of running the (incredibly large) city. The overarching head of the former is the Mayor, who is elected directly by the people and held accountable by the 25-member legislature underneath him: also popularly elected. Then there are 32 separate boroughs, further divided into ‘wards’ that are each headed by three elected councillors and responsible for executing decisions.

A fundamental aspect of effective governance is the availability of granular, updated information that can be acted upon in as swift and seamless a manner as possible to address the needs, desires, and grievances of ordinary people. This knowledge is crucial, as contextual details always vary: policies that may be advisable in one district, for instance, can be quite wasteful in another. The primary mechanism through which this challenge can be addressed, and is indeed so across the globe, is via local government bodies that are both financially and administratively empowered. This means both an ‘executive’ body in charge of the governance of particular regions – such as districts or divisions – whose members are directly elected by, and thus accountable to, the people of those regions while also facilitating the ‘directional’ desires of the provincial head, in this case the Chief Minister. Furthermore, each of these regions must – if they are to serve any function – be empowered financially. This can be based on simple population statistics or can have added incentive mechanisms such as reduction in out-of-school-children, graduation from welfare programs, improvements in agricultural productivity, etc.

In Pakistan, the 18th Amendment functioned to devolve powers down to the level of provinces – granting them autonomy over functions including but not limited to education, healthcare, policing and criminal procedures more generally, urban planning, and environmental management. It also assigned total autonomy to each of the provinces in terms of their internal governance, legislative affairs, and financial transactions. Finally, the National Finance Commission (NFC) Award was restructured to add factors other than population – such as poverty/backwardness and revenue collection – so as to introduce an element of equity to the mix. While this was a welcome initiative, its net impact was to relocate the locus of power from the federal government to the provinces: with ‘ordinary citizens’ hardly included in key decision making processes. This has led to wide ranging debates about the Provincial Finance Commission, which by many accounts ought to follow the same logic of the NFC down to lower levels of government.

In provinces like Sindh, this has meant the continued dominance of big landlords that have maintained a coercive control over their respective communities – ensuring their votes to the same party term after term in exchange for personal rewards in an elaborate system of patronage politics. Legislators in both provincial and national assemblies, for instance, are ‘electables’ that hardly have any interest in forgoing their foothold in the corridors of power: and it is unlikely that they would support large scale devolution. This has naturally meant both a historic neglect of rural areas from a governance point of view and consistent underdevelopment of urban spaces, which continue to prioritise cars over public transit, sprawl over density, and elitism over inclusivity. The political economy of this domain, therefore, is crucial: how can settlements between various brokers be made to advance this cause?

Devolution for its own sake is not the proposal here. There is, as pointed out by various scholars, a point at which this pursuit generates diminishing returns: a case in point being the floods of last year. In the context of a largely absent state apparatus, the NGO sector jumped in to address the most pressing concerns of disaffected communities at the time. While laudable, these efforts were generally scattered and ad-hoc in their nature. Without a clear centralised body coordinating efforts via the sharing of real time information about regions in need of attention, a certain saturation of ‘assistance’ was observed – with too many NGOs in places that did not need them and too few in those that did. This was a real time example of how decentralisation can, at times, lead to perverse outcomes.

In this issue of Discourse, we attempt to highlight the nuances that are – and will be – involved in a process of wide-scale decentralisation in Pakistan. In this spirit, we outline actionable steps that may be taken by ruling elites to move towards wider power sharing arrangements, the historical path dependencies and political economy factors that may hinder and obstruct such an initiative, and the various questions that must be answered to establish clarity on what – in terms of specifics – the ideas of devolution, localisation and delegation even mean?

We hope that this can serve as a conversation (or discourse!) starter for how Pakistan can move towards genuine democracy by involving people in governance procedures and allowing them a central place in choosing what sort of policies they desire. With a diverse range of viewpoints (as is generally the case in our publications!), we hope the following pages offer insight into the world devolution – with all its messiness and linkages to other parts of economic affairs. If you enjoy it, be sure to continue the conversation on our social media platforms and let us know your thoughts!