COVER STORY

Pakistan currently finds itself in a situation in which the threat of sovereign default hangs upon the people like a sword suspended on a string. Essentially, what this means is that external creditors – whether that be in the form of multilateral institutions or bilateral partner countries – may not receive their scheduled repayments on time. A fundamental reason for this is that Pakistan has experienced a consistent balance of payments crisis – in which exports and remittances have failed to match earnings from exports, leading to dwindling foreign exchange reserves that are used for external financial transactions of all kinds.

There are several reasons why this is a grave predicament for the country. First, defaulting on external debt obligations would mean the tanking of Pakistan’s credit rating in the international financial community – thus drastically reducing the prospects of any further loans from external parties. For a country that is consistently in a fiscal account deficit (government expenditures exceeding revenues), this will mean further cutbacks to crucial sectors such as energy, education, healthcare, social protection, industrial development, etc. which will add fuel to the fire of inflation, potentially leading to popular uprisings and political instability. Furthermore, sovereign default is generally always followed by capital flight due to investors losing faith in the government to ensure adequate conditions for commercial activity: leading to business closures, livelihood losses, further devaluation of the currency, and a sustained economic recession that will push large swaths of the population into acute poverty.

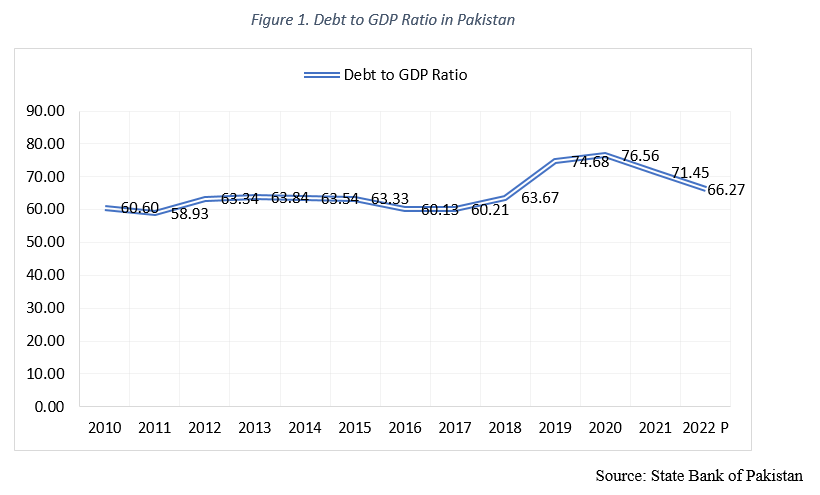

As a percentage of GDP, Pakistan’s debt obligations stood at approximately 60.6% in 2010, steadily rising over the subsequent 5-7 years before shooting up and peaking at a whopping 76.6% in 2020. In the subsequent two years, the figure fell back down – going to 71.5% in 2021 and 66.27% in 2022 as shown in Figure 1.

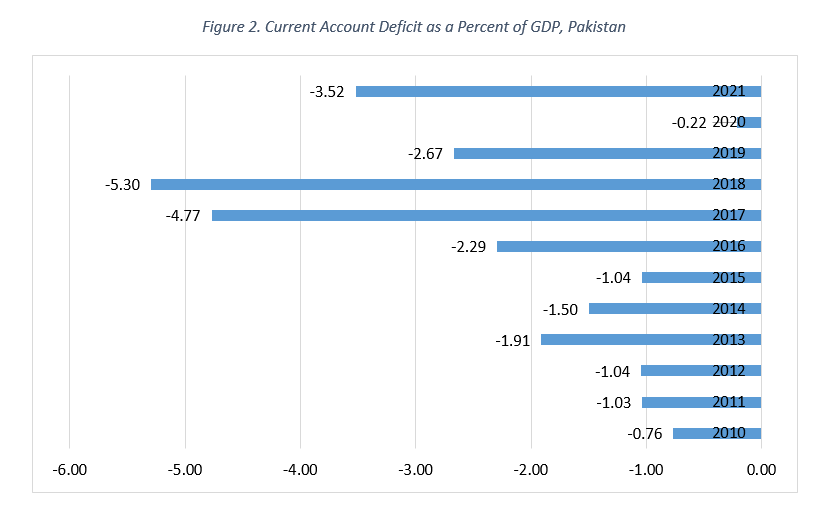

On the other hand, the current account deficit – which illustrates the difference between foreign currency inflows and outflows, i.e. the surplus of imports over exports and remittances – has been consistent across the previous two decades. Over the past 5-6 years, however, there has been an alarming increase – jumping from an annual average of 1.21 percent of GDP in the 2010-2015 period to 3.13 in the 2016-2021 period. This is naturally cause for great alarm, as it must be met via credit – further adding to sovereign debt troubles faced by the government of Pakistan. Figure 2 offers a breakdown.

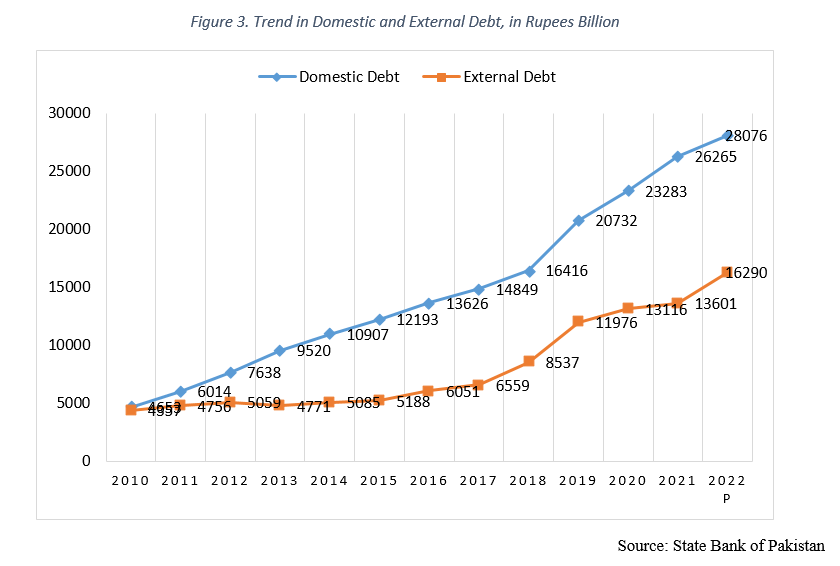

External debt in Pakistan has risen from approximately Rs. 4.36 trillion in 2010 to Rs. 16.3 trillion in 2022 – quadrupling over the time period. This figure was generally under control until 2017, at Rs. 6.56 trillion (an annual average growth of Rs. 315 million) – but quickly spiralled shortly afterwards. During the 2017-2022 period, external debt rose from Rs. 6.56 trillion to a whopping Rs. 16.3 trillion: an annual average growth of Rs. 1.95 trillion. The situation with domestic debt was not better, which rose from Rs. 4.65 trillion in 2010 to Rs. 28.1 trillion in 2022 – an almost six-fold expansion. Breakdowns in Figure 2.

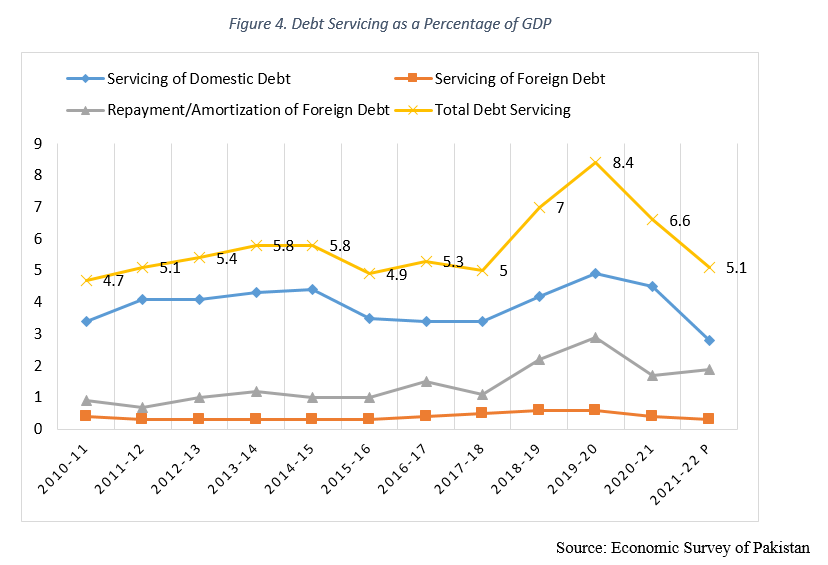

As a percentage of GDP, debt servicing – i.e. the returning of principal amounts to creditors as well as interest charges on borrowed finance – fell in the range of 4 to 9. The highest was in the 2019-20 fiscal year, when it hovered around 8.4 as illustrated in Figure 3. To put this into perspective, government expenditure as a percentage of GDP on education and healthcare has never gone above 3% in the previous decade. Considering that the overall debt burden has only risen over time, these figures on servicing suggest that despite slashing a significant amount off the government’s available funds and resultantly leaving less for crucial development expenditures, they are simply insufficient in meeting obligations.

Going forward, debt repayments in the foreseeable future are estimated at approximately USD 35 billion per annum on average. Of this, USD 25 billion forms the amounts owed to external lenders while the remaining USD 10 billion constitutes the estimated current account deficits in the coming years – at least until 2027. This has prompted wide ranging debate and discussion on the need for sovereign debt restructuring: which is an intricate process of negotiations with creditors to revise the terms of the debt agreement such that it is less burdensome on the country in question. There are various forms debt restructuring can take, including but not limited to: rescheduling, reductions, principal haircuts, and deferrals.

Pakistan has had two formal instances of sovereign debt restructuring, the first over the course of the 1970s and the second around the turn of the millennium. In the former instance, debts were restructured in the context of the oil crisis – in which prices were shooting up at a rapid rate and adversely impacting the country’s balance of payments. Furthermore, the Bangladesh War of Independence had also recently taken place – in 1971 – causing several major disruptions to the country’s finances. In response to this, Pakistan underwent its first sovereign debt restructuring which was largely based around revising timelines to debt repayment obligations. Details listed in Table 1. Next, the second – large scale – initiative in this vein took place around the 1999-2001 period in the aftermath of the dismal economic management of the 1990s, along with the nuclear tests of 1998 which came with sanctions from the international community. After 9/11 however, a 180-degree shift was experienced – in which Pakistan received tremendous assistance from the international community, particularly the Paris Club, for its involvement as an ally in the War on Terror. This was Pakistan’s largest ever debt restructuring, largely revolving around its Eurobonds. These were agglomerated and the payment period revised, along with various other stipulations listed in Table 2, which functioned to create tremendous fiscal space and restructured debts amounting to USD 19 billion.

Table 1. History of Pakistan’s Sovereign Debt Restructuring

| Period | Context | Type of Restructuring | Salient Outcomes |

| 1971-1978 | Following the Bangladesh War of Independence, Pakistan’s ability to meet its external debt obligations was severely depleted. Furthermore, it was yet to be determined how these debts would be split between Pakistan and Bangladesh, and this uncertainty prompted creditors to pause payments temporarily. This led to a series of moratoriums in which creditors allowed for more time. Initially, this suspension of payments was set to take place until May 1971 – but was ultimately extended to June 1974. Following a World Bank study during this period, pauses on repayments were further extended to December 1978. | Rescheduling | Approximately 56% of debt servicing obligations over the period 1973 to 1977 were rescheduled (via moratoriums) – offering much needed fiscal space to Pakistan’s economy following the war. |

| 1998-2001 | Following the nuclear tests of 1998 and the subsequent sanctions from the international community, Pakistan underwent a period of severe balance of payments crises – leading to piling sovereign debts which reached 89-92% towards the end of the millennium. Eurobonds were primarily targeted under this initiative (with the Paris Club), and a series of small obligations (in the range of USD 160-300 million) were replaced by one consolidated bond with a 6-year maturity period, a 10% coupon payable semi-annual, a small nominal increase in principal, and a three year grace period on principal payments. Furthermore, Pakistan rescheduled commercial loans with the London Club with a face value of USD 929 million. Finally, two further agreements with the Paris club (USD 1.75 billion and USD 12.5 billion) were also arranged during this period in the backdrop of Pakistan’s involvement in the War on Terror. | Conversion | USD 19 billion was successfully restructured over this period, amounting to 1/3rd of GDP at the beginning of the initiative. |

Several experts have, in recent months, claimed that in the absence of debt restructuring, Pakistan is almost certain to default on its obligations – leading to a catastrophic downward spiral. Others, however, have claimed that debt restructuring is not the panacea it is sold as but rather simply a strategy of buying time and forestalling the need to pursue radical institutional reform and address the root causes of why the country finds itself in this predicament in the first place. Of course, there is truth to this. The reason for low levels of export, for instance, is linked to a failure to incubate and promote human capital: which can then engage in entrepreneurship, industrial growth/development, freelancing gigs, etc. that in turn – if done well – will generate export revenues that eventually exceed imports and allow for the fiscal space to resolve the debt crisis.

This is easier said than done – and is fundamentally linked to the question of governance and institutional arrangements. The primary reason for Pakistan’s failure to adopt pro-people policies is that the extractive colonial-style bureaucracies of yesteryear continue to prevail: leeching resources from the economy which have been estimated by the UNDP to be Rs. 2.7 trillion on an annual basis. The failure to reform these, and to not pursue genuine democratisation – in which political leadership is actually attuned and responsive to the needs and demands of the citizenry – is precisely why the country finds itself on the brink today. Specific power centres – including the security apparatus, big landlords, industrial rent-seekers, civil bureaucracies, corporate conglomerates, and international financial institutions – are who leaders seem to be catering to rather than the ordinary person, and it is thus no wonder that the ‘twin deficits’ crisis continues unabated.

The thematic section of this issue of Discourse is about two primary topics: a) possible technical interventions that can help Pakistan meet its debt obligations via various means of restructuring, and b) the political economy of sovereign debt, which constitutes the set of factors responsible for the situation the country finds itself today. With a diverse range of viewpoints (as is generally the case in our publications!), we hope the following pages offer insight into the world of sovereign debt – with all its messiness and linkages to other parts of economic affairs. If you enjoy it, be sure to continue the conversation on our social media platforms and let us know your thoughts!

Yours sincerely,

Editorial Board

Discourse Magazine

Pakistan Institute of Development Economics

P.S. We would like to extend our heartiest gratitude to Syeda Um ul Baneen, PhD Econometrics from the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics (PIDE), Islamabad, for the graphical illustrations used in this cover story.