Electoral Politics in Pakistan: Law, Parties, and the Need for Innovation

Electoral Politics in Pakistan: Law, Parties, and the Need for Innovation

With three long dictatorial regimes, frequent allegations of electoral rigging, dynastic parties, and an ever-expanding state with limited class mobility, Pakistan’s political landscape has consistently failed to meet the desires of ordinary people. This paper intends to outline the pitfalls of the electoral system through a three-tiered analysis of law, party behaviour, and potential technical interventions that may reshape the incentive structures guiding contestations for political power—thus leading to enhanced levels of political representation for citizens.[1]

- LOW TURNOUT AND MISTRUST DUE TO FLAWED LAW

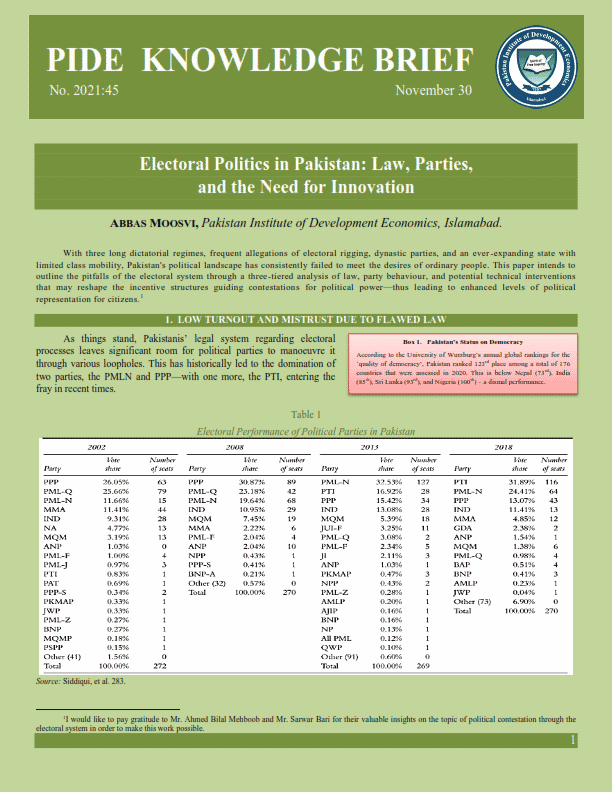

As things stand, Pakistanis’ legal system regarding electoral processes leaves significant room for political parties to manoeuvre it through various loopholes. This has historically led to the domination of two parties, the PMLN and PPP—with one more, the PTI, entering the fray in recent times.

| Box 1. Pakistan’s Status on Democracy According to the University of Wurzburg’s annual global rankings for the ‘quality of democracy’, Pakistan ranked 123rd place among a total of 176 countries that were assessed in 2020. This is below Nepal (73rd), India (85th), Sri Lanka (93rd), and Nigeria (100th) – a dismal performance. |

Table 1

Electoral Performance of Political Parties in Pakistan Source: Siddiqui, et al. 283.

Source: Siddiqui, et al. 283.

[1]I would like to pay gratitude to Mr. Ahmed Bilal Mehboob and Mr. Sarwar Bari for their valuable insights on the topic of political contestation through the electoral system in order to make this work possible.

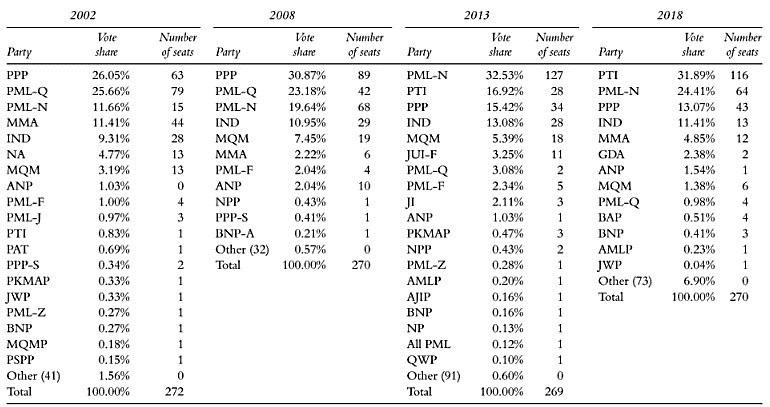

It is also one reason for low turnouts, with no more than 55 percent of voters turning in their ballots on election day in any given cycle (a figure that declined in the 2018 election cycle)—indicating a dismal level of trust in the system to generate any substantive change.

Table 2

Statistics on Voter Turnout Source: Free and Fair Elections Network.

Source: Free and Fair Elections Network.

1.1. Procedural Loopholes in the Law

One of the main reasons for the low turnout is the failure of the legal system to break down the election process into its various constituent elements and stipulate laws specific to them. The absence of these procedural laws has led to frequent malpractice in multiple areas, including the secrecy of the vote, equality of suffrage, candidacy requirements, periodicity of elections, definitions of electoral systems/provisions, right of association, voting rights, and the remedies for their violations, and campaign conduct.

The Elections Act, in Chapter III, Section 14, does state that the Commission is responsible for preparing an action plan four months prior to the election—“specifying all legal and administrative measures that have been taken or are required to be taken”—but this stipulation is far too generic and ill-defined. (Consolidating Democracy for Pakistan, 9) The current law treats elections as one homogenous event rather than a series of procedures—leaving too much room for meddling at the micro-level: see Box 2.

| Box 2. Procedural Law for Elections A comprehensive legal framework for political contestation must cover each of the electoral stages adequately. (Mirbahar, 6-7) This means detailed legal provisions for 11 areas, which are absent/ underdeveloped in Pakistan’s current legal system: 1. Electoral administration. 2. Election system. 3. Rights of candidates. 4. Right to vote. 5. Voting procedures. 6. Boundary delimitation. 7. Transparency requirements. 8. Campaign regulations. 9. Counting and compilation of results. 10. Women’s participation. 11. Participation of persons with disabilities. |

A study by Mirbahar (2019) on local government elections revealed, for instance, that executive positions for district council level in Sindh (for mayor) and Balochistan (for chairman) are frequently decided by a show of hands—thus compromising the secrecy of the vote. Furthermore, electoral units—i.e., the number of people designated to vote at a particular polling station—are rarely ever equal in their sizes (especially in Sindh and Punjab) within a constituency. This leads to inefficient use of election personnel and congestion in densely populated regions—making the voting process cumbersome for citizens and violating the principle of equality of suffrage. Also, the imposition of arbitrary cut-off dates to register for voting in these elections is not uncommon. The option to appeal for remedies of these rights violations is not formally included in the law (Mirbahar, 2019). Legal stipulations for all these loopholes must be introduced to standardise the process, making it fair and predictable.

Finally, a lack of transparency from the Election Commission of Pakistan seemed to prevail in the 2018 cycle—whereby it remained unclear how decisions were taken by key personnel during polling periods. This is because no formal publications from the EC were released for public scrutiny and clarification. These decisions had to do with the processes through which constituencies were delimited, the disqualification of certain candidates, court decisions on the scrutiny of candidates, the nomination of candidates for reserved seats (women and minorities), among others. Worse still is that no formal/legal provisions for publishing information relating to key decisions is to be found, meaning that the EC was technically within its rights not to share the information. This indicates a lack of accountability mechanisms and a conducive legal environment for poor levels of transparency. (European Union, 2018).

1.2. Ambiguities and Unintended Consequences in Law

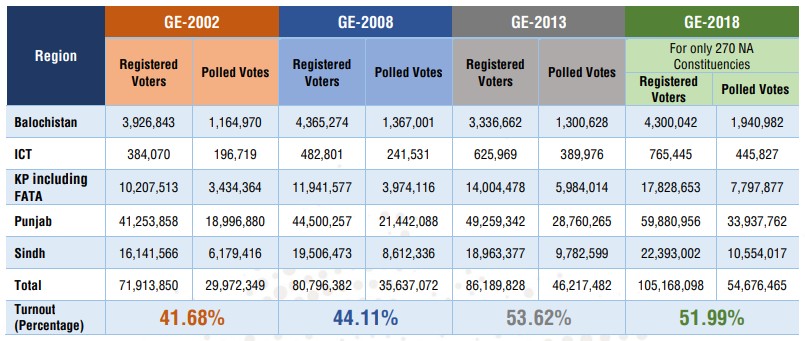

The Election Bill of 2017, the legal document widely seen as the dominant source for all things relating to contestations for political office in Pakistan, leaves much to be desired. The Free and Fair Elections Network (FAFEN) released a review of the bill shortly after its release, documenting its shortcomings and proposing changes (see Box 3 and Table 3).

Box 3. FAFEN Recommendations on Elections Act 2017

Increase the percentage of tickets that political parties are mandated to reserve for women and minority groups, currently at just 5 percent.

Allocate election staff to polling stations that they themselves do not belong to in order to minimise bias.

Raise the minimum turnout requirement for women, currently at just 10 percent.

Democracy necessitates basic freedoms without any discrimination—including the “freedom of speech, information, movement, association, and assembly, as well as the right to vote and to stand.” (European Union, 2018) In Pakistan, however, this is not possible under current legal stipulations. For instance, the constitution allows for rights to be suspended based on ‘any reasonable restriction imposed by law’ (Chapter 1, Article 16), which can easily lead to the arbitrary imposition by those in power whenever necessary/useful. Another issue is blasphemy laws, which undermine the concept of free speech through explicit intimidation (threat of accusation), and a culture of self-censorship, which is a by-product of the fear surrounding the topic. Finally, arbitrary conditions relating to ethics, morals, mental fitness, etc. (Articles 62/63 of the Constitution) that have no relationship to the ability to govern are part of the law, thus restricting candidacy for political office and violating the principle of the right to stand. (European Union, 2018).

1.3. Failure to Administer the Law

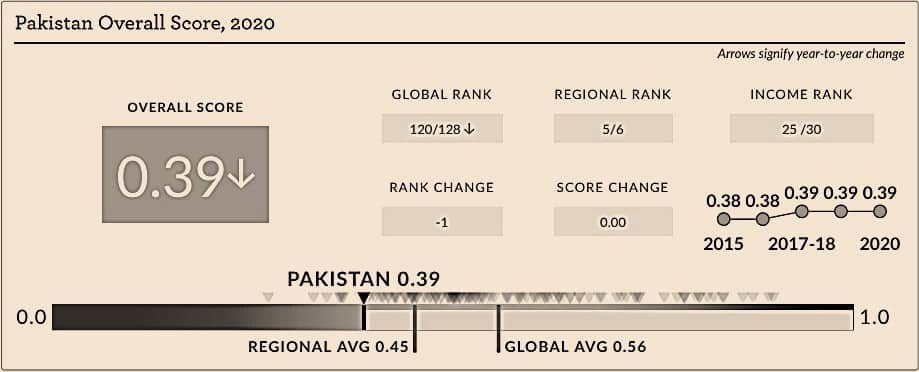

Of course, this is not to say that merely passing bills in parliament is the surest route towards participatory democracy. Pakistan was ranked 120 out of 128 countries in the World Justice Project’s—2020 index for rule of law—suggesting that the implementation of law is a significant hurdle. Therefore, legal interventions are unlikely to create substantive change unless administrative procedures executing the election process are radically rethought, modernised, and executed—failure of which is equivalent to not meeting constitutional stipulations.

Fig. 1. Pakistan’s Rule of Law Status Source: World Justice Project, Rule of Law Index.

Source: World Justice Project, Rule of Law Index.

The Election Commission of Pakistan’s internal report on the 2013 cycle, which outlined the various bottlenecks in the process, is a source of several insights into administrative failings during elections. Problems included an excessively large election staff (>650,000) that was inadequately trained; Returning Officers not being reimbursed for their operational costs, and no transport services provided to polling staff—all leading to frustration and low morale levels. This was exacerbated by the fact that the military had not made its security plan known to polling station personnel, leading to confusion and disarray on election day. Perhaps most concerning of all was a lack of senior officers: “One Secretary, one Additional Secretary, two Directors-General, one Joint Secretary, and six Additional Directors-General, plus the four provincial election commissioners” was the core team in charge of administering the elections. (Niaz, 2020) To make matters worse, this small group of individuals was picked from other services of the civil bureaucracy—thus having no technical expertise in the planning, management, or execution of elections. Other concerns were resource constraints, coordination mechanisms between monitoring teams and central bodies, and delays with the Results Management System (RMS) due to incompetent operators.

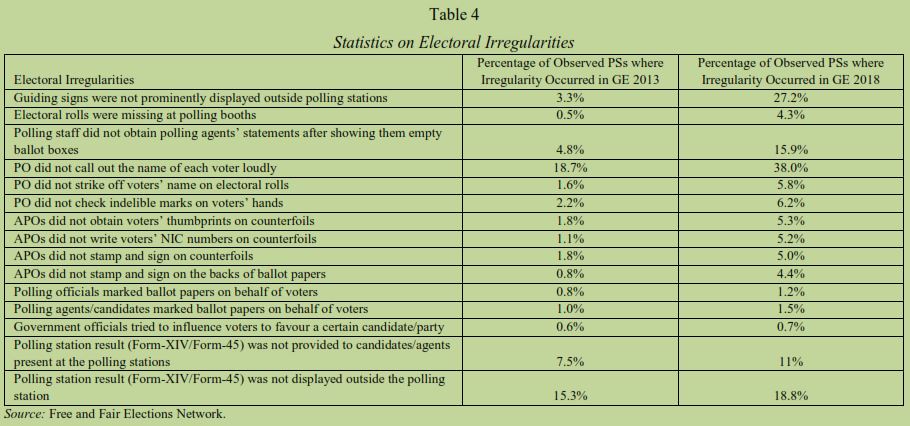

In the 2018 election cycle, things seemed to improve a little regarding upholding the principles of secrecy of the vote, reductions in campaign material, and mitigating instances of violence—partly due to the Elections Act of 2017 and its stipulations. However, even these contestations were ultimately mired by allegations of rigging—and a series of pitfalls were faced on election day. Firstly, a lack of cooling facilities in polling offices led to excessive levels of fatigue for polling officers who found it difficult to conduct their jobs seamlessly. Furthermore, some hurdles with Forms—45 and 46 (relating to tallying votes and presenting them to candidates) were faced—and a series of political parties claimed that they did not receive these at the time of counting. Next, in the transmission stage—where results are transferred from polling stations to their returning officers—a host of hurdles were faced with the smartphone-based technology used for this purpose eventually collapsing. Finally, it took almost two full days for results to be officially transmitted to the ECP in their entirety—which is far too long and leaves excessive room for meddling (Mehboob, ??? ) A list of election irregularities on a minor scale were also observed (more so than the previous cycle), of which a breakdown is presented in Table 4.

An election process that contains this many flaws cannot possibly be considered a ‘free and fair’ one—and it is only inevitable that losing parties invariably make the accusation of rigging rather than accepting defeat. The implementation of the law, therefore, failed—and has been failing.

2. POLITICAL PARTIES AND INCENTIVE STRUCTURES

As per the Elections Act-2017, parties in Pakistan can be formed by ‘anybody of individuals or association of citizens’—and indeed, over 200 parties contested in the election cycle of 2018. This results in scattered seats and problems forming government—with various parties holding a small number of seats and imposing a set of conditions upon prospective ruling parties for coalition agreements. Naturally, these conditions, which are frequently motivated by the personal interests of the members rather than the wishes of their constituencies, function to dilute the ideological base of a government—resulting in the wastage of resources and deadlocks in parliament.

One way to overcome this can be by imposing more prerequisites, ratified by law, for parties to appear on the ballet, which could be in the form of demonstrating a minimum support base beforehand—for instance through signatures from guaranteed voters or a certain number of individual donations (exceeding a minimum amount) from alleged supporters. This can be extended further, and conditions geared to promote political competition at a local level may be introduced, for instance, by mandating parties to demonstrate a certain minimum number of supporters in each district of a province before being allowed to compete for its assembly—thus prompting all parties to expand their networks in remote, rural regions, leading to a more egalitarian basis of politics across the country over the long run. Historical strongholds, e.g., PPP in Sindh, may be forced to up the ante in terms of their performance as they begin to face competition in areas they took for granted—and it would also encourage smaller parties, that have closer ties with local communities, to enter the foray and attain greater levels of success.

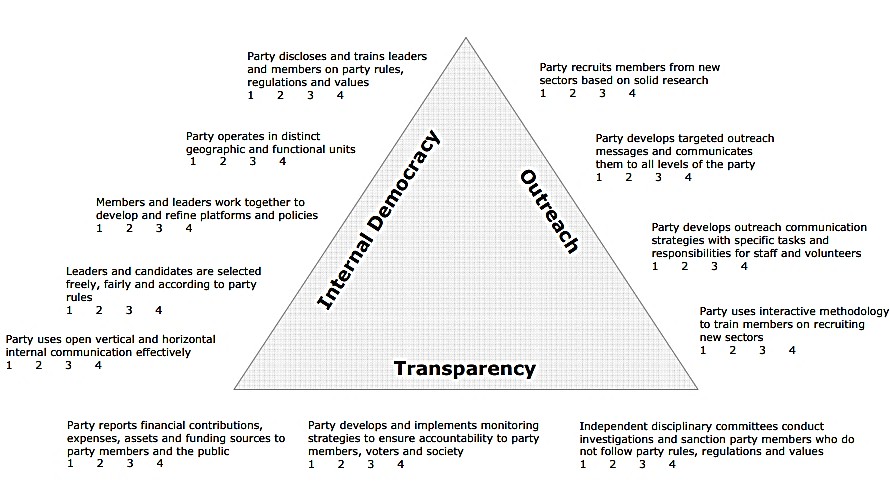

Fig. 2. Elements of Effective Political Party Activity Source: National Democratic Institute.

Source: National Democratic Institute.

Furthermore, political parties—before being allowed to compete for the government—should be mandated to have internal party elections regularly (minimum of once per year) in a public capacity which is conducted by an independent third party (such as the Election Commission) that can ensure its transparency, fairness, and legitimacy. Records of all these contestations, along with detailed documentation of the party’s past performance—in terms of the proportion of promises they have delivered on—ought to become a regular part of the functioning of democracy in Pakistan in the form of a barometer that is regularly updated and assesses the extent of internal democracy in each political party. These measures will lead to an enhanced level of accountability and work against the domineering role of family politics, in which one specific lineage is constantly occupying the top positions regardless of performance or technical competence.

Another point for political parties is the need for financial transparency. Every political grouping, in order to compete in elections, must have their accounts audited by independent organisations and compiled into reports that are freely accessible to the public. This will act as a disincentive for parties to accept massive sums from corporate entities and foreign sources motivated by certain agendas that have to do with self-interest and/or geopolitical considerations. According to Ahmed Bilal Mehboob, one of the country’s foremost experts on electoral politics, the legal framework around which campaign financing takes place is a robust one—the bottlenecks largely having to do with its proper enforcement. For this, the Election Commission’s Political Finance wing will have to be invested in: its capacity enhanced, its political will strengthened, and the technical competencies of its members expanded. This will allow for close monitoring and swift action if/when a situation arises. So far, the PF wing has proven to be ineffective—having had over 70 hearings in the past 6.5 years and only passing around 24 orders: a large proportion of which were not even complied with. This casts a shadow over the electoral process and constrains the process of democracy in Pakistan. (Mehboob, Year ???)

Finally, the size of cabinets is excessively large as things currently stand. The law currently places a limit on this, which is 11 percent of the size of parliament—but this amounts to almost 50 members, leading to bureaucratic hurdles in the decision-making process within the executive branch of government. (Mehboob, ????) These laws need to be revised to incentivise the merger of similar ministries and instill a broad hierarchical organisation of departments (rather than a narrow one) to streamline the process and mitigate against rigidity and staleness—replacing them with dynamism, creativity, teamwork, and technical competence.

A set of recommendations has been put forth in a proposed amendment to the Elections Act in May 2021, entitled the ‘Election (Amendment) Bill, 2020’. These include requirements for political parties to demonstrate a minimum of 10,000 members (rather than 2,000)—including a minimum of 20 percent women—before being allowed to enlist for elections. Furthermore, overseas Pakistanis are to be granted voting rights, electronic voting machines are to be used for transparency, and specific timelines for various election procedures are to be established (Dawn, date ). These are positive steps, but they were rushed out before being fully thought through—with a clear failure to take procedural/practical considerations into account—leading to strong opposition from the Election Commission, which refused to accept 28 of the 62 amendments due to excessive loopholes in their administrative aspects. Besides these, the ECP also felt certain proposals were discriminatory and would inadvertently preserve the status quo—such as the requirement of 10,000 members: working against smaller parties in regions with a smaller population. Rather than the number of members, requirements to enlist ought to be based on the size of support bases to avoid incentivising parties to induct members purely for the sake of it—which would naturally lead to excessive internal dormancy (Dawn, date).

- MODERNISING THE SYSTEM VIA DYNAMISM, INNOVATION, AND ENHANCED REPRESENTATION

There is a need to rethink the incentive structures that guide the political process in Pakistan. Merely amending legal stipulations to eliminate present loopholes, although necessary, will only create a difference if/when their proper execution is all but guaranteed: a task that Pakistan seems a long way away from ensuring, as this paper has illustrated. This calls for the introduction of a new set of interventions that have shown promise around the world and which developed nations have begun to incorporate into their systems to enhance the level of legitimate representation.

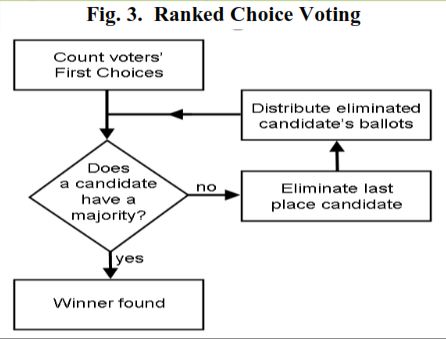

Ranked Choice Voting. This is a system based on proportional representation whereby candidates are ranked by voters in order of preference, and a winner is decided through an elimination process. An outline of the system is presented in Figure 3.

This system is such that elimination and redistribution of votes continues until a majority is achieved—thus ensuring that the wishes of the electorate are successfully represented, and avoiding the pitfalls of the ‘First Past the Post’ system, which awards candidates with governing privileges when they do not have the backing of a majority. In other words, it ensures no ‘wasted’ votes. Further, it enhances the level of competition for political power—acting against pressures for polarisation and concentration of authority within a few hands by removing the need to ‘vote for the lesser evil’, a common idea peddled by the supporters of mainstream ethnic and fiefdom-like parties that have long occupied the corridors of power. Ergo, it incentivises all contestants to appeal to as wide an audience as possible—thereby bringing the most pressing societal needs to the fore and creating pressures on politicians to think pragmatically rather than just appealing to a set, predetermined demographic/support base. Furthermore, the likelihood of women/minorities winning seats has shown to drastically increase under proportional representation systems as compared to FPTP ones, in some cases almost doubling—as was the case in 1995, documented by the Inter-Parliamentary Union in a study of several countries that had transitioned to the new system (ACE). In summation, ranked choice voting resolves several pitfalls of conventional electoral systems by “creating and protecting a more civil commons, where more perspectives are included, respect is encouraged, coercion and distortion are minimised, and intersubjective bridging is rewarded.” (Anest, 2009).

This system is such that elimination and redistribution of votes continues until a majority is achieved—thus ensuring that the wishes of the electorate are successfully represented, and avoiding the pitfalls of the ‘First Past the Post’ system, which awards candidates with governing privileges when they do not have the backing of a majority. In other words, it ensures no ‘wasted’ votes. Further, it enhances the level of competition for political power—acting against pressures for polarisation and concentration of authority within a few hands by removing the need to ‘vote for the lesser evil’, a common idea peddled by the supporters of mainstream ethnic and fiefdom-like parties that have long occupied the corridors of power. Ergo, it incentivises all contestants to appeal to as wide an audience as possible—thereby bringing the most pressing societal needs to the fore and creating pressures on politicians to think pragmatically rather than just appealing to a set, predetermined demographic/support base. Furthermore, the likelihood of women/minorities winning seats has shown to drastically increase under proportional representation systems as compared to FPTP ones, in some cases almost doubling—as was the case in 1995, documented by the Inter-Parliamentary Union in a study of several countries that had transitioned to the new system (ACE). In summation, ranked choice voting resolves several pitfalls of conventional electoral systems by “creating and protecting a more civil commons, where more perspectives are included, respect is encouraged, coercion and distortion are minimised, and intersubjective bridging is rewarded.” (Anest, 2009).

Staggered and Direct Elections. This is when elections for political office within a certain organ of government, for instance, the senate, do not all take place in one go. Instead, two (or more) groups of seats are created—for which candidacy is borne at different times. If a term is for five years, then elections will take place every 2.5 years: separately for each group. With more frequent election cycles, a spirit of accountability to constituencies is introduced—thus incentivising the governance system to actually meet its stated promises to the people. From a technical standpoint, this will increase the level of activity within the institution in question, now that a minimum of 50 percent of parliamentarians are in ‘election mode’ at any given point in time. A staggered system also introduces more stability to the political process as a whole, especially if its application is broad, as a full-scale reset of any major institution is never made (Goetz, et al. 2014). It has also been demonstrated that intra-party solidarity generally tends to prevail under this system but in a different manner to conventional politics. Firstly, party members are more likely to offer support to colleagues that take occasional departures from the party’s traditional line, as there is now less at stake—leading to more fluid ideologies that are tied more to circumstances than symbols and shibboleths. Furthermore, speeches and public appeals within the institutions would be less cumbersome—as members that are not due for re-election in the upcoming cycle are likely to grant their podiums to party fellows that are, thus freeing up time and allowing for deeper, more nuanced debates on important societal issues (Willumsen, et al. 2018). To extend this further, direct elections for the Senate, as well as the Presidency, may be introduced—thus limiting the powers of parliament and installing more checks and balances to the system (Haque, 2017).

Tax Choice. This is a system that allows voters the choice to decide how tax expenditures are to be allocated—and to count these preferences regardless of whether their chosen candidate ultimately wins. This strategy would ease societal pressures to generate a ‘cult of personalities’ and introduce a semi-direct form of government—in which the electorate, or taxpayer, gets to decide which areas (education, healthcare, infrastructure, corporate subsidies, etc.) their contributions are being spent on. One benefit of this would be that it could lead to higher turnouts during election cycles, in which people are incentivised to participate due to a personal stake they now have in the outcome. This is likely to expand the tax net as well, with increasing numbers of citizens (particularly those leaning conservative or libertarian) willing to pay due to the knowledge that they are in control of where their money is going—and that they now have the freedom to empower the causes that they believe in rather than what powerful interests prefer (Lamberton, 2016).

Deciding the Dominant Political Player. Voters could also be granted the option to empower certain institutions or organs of government for the upcoming term through elections—whether that be the cabinet, judiciary, legislature, military, etc.—thus involving them further in the political process and granting them the power to decide, based on their perceptions of the emergent sociopolitical landscape, who gets priority in a conflict of interest. At a constitutional level, this would also introduce a sense of dynamism through built-in flexibility to the legal structure by introducing conditional (if-then) laws—thus allowing for more context-specific rule of law, rather than one based on outdated principles and traditions carrying forward from colonial times.

Finally, no discussion about democratic processes is complete without discussing factors exogenous to the elections cycle—including the role of media, student unions, feudalism, clientelism, devolution, education, civil service, foreign aid, civil society, and rule of law. These important facets will be explored in another paper that analyses the political economy of democratisation in Pakistan.

REFERENCES

ACE Encyclopedia Version 1.0. https://aceproject.org/main/english/es/esd01b.htm

Anest, Jim (2009). Ranked choice voting. Journal of Integral Theory and Practice, 4(3), 23–40.

Breth, Erica & Julian Quibell (2018). Best practices of effective parties: Three training modules for political parties. Washington, DC: National Democratic Institute for International Affairs (NDI). 2018.

Consolidating Democracy in Pakistan: The Elections Act, 2017—An Overview. https://pakvoter.org/wp-content/ uploads/2018/06/Overview-of-Elections-Act-2602184.pdf

ECP alarmed at 28 clauses of electoral reforms bill. https://www.dawn.com/news/1629570

European Union Election Observation Mission (2018). Final report general elections, 25 July 2018. http://www. eods.eu/library/final_report_pakistan_2018_english.pdf

FAFEN Review and Recommendations on Elections Bill 2017. Free and Fair Election Network. (2018, April 6). https://fafen.org/fafen-review-and-recommendations-on-elections-bill-2017/.

Free and Fair Elections Network (2019). Election Day Process: Observation and Analysis. https://fafen.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/FAFEN-General-Election-Observation-2018-Election-Day-Process-Analysis-Pakistan.pdf

Goetz, Klaus H., et al. (2014). Heterotemporal parliamentarism: Does staggered membership renewal matter? ECPR Joint Sessions, Salamanca.

Haque, Nadeem Ul (2017). Looking Back: How Pakistan Became an Asian Tiger by 2050. Kitab (Pvt) Ltd.

How Many Ministers. https://ahmedbilalmehboob.com/how-many-ministers-dawn/

Lamberton, C. (2016). Your money, your choice. Democracy Journal. https://democracyjournal. org/magazine/20/your-money-your-choice/.

Mirbahar, Hassan Nasir (2019) Flawed laws, flawed elections: Local elections in Pakistan. Election Law Journal: Rules, Politics, and Policy, 18(1), 1–15.

NA Panel Clears Bill to Amend Elections Act. https://www.dawn.com/news/1628304/na-panel-clears-bill-to-amend-elections-act

Niaz, Ilhan (2020). The need for reforms in the light of 2013 report of the election commission of Pakistan. Journal of Social Sciences & Humanities (1994-7046), 28(1).

Norris, Pippa (2013). The new research agenda studying electoral integrity. Electoral Studies, 32(4), 563–575.

Proportional Representation Voting Systems. https://www.fairvote.org/proportional_representation_voting_systems

Ranking of Countries by Quality of Democracy. https://www.democracymatrix.com/ranking

Shafqat, Saeed, et al. (2020). Pakistan’s political parties: Surviving between dictatorship and democracy. Georgetown University Press.

Test Case of Political Finance. https://ahmedbilalmehboob.com/test-case-of-political-finance-dawn/

The Challenges of Election Day. https://ahmedbilalmehboob.com/the-challenges-of-election-day-dawn/

Willumsen, David M., Stecker, Christian, & Goetz, Klaus H. (2018). The electoral connection in staggered parliaments: Evidence from Australia, France, Germany and Japan. European Journal of Political Research, 57(3), 759–780.

World Justice Project (2020). WJP Rule of Law Index, Pakistan. https://worldjusticeproject.org/rule-of-law-index/ country/2020/Pakistan