Foreign Aid Effectiveness: The Relationship Between Aid Inflows and Economic Growth

Abstract

Has the process of foreign-led assistance/development fostered economic growth and development around the globe? Reviewing the literature, this paper charts out the foreign aid landscape, in terms of its salient stakeholders, operational dynamics, and historical evolution, following which an attempt is made to offer a comprehensive summary and analysis of the academic literature on the phenomenon.

Results were generally mixed, with some authors suggesting a positive relationship, others a negative one, and others still claiming excessive heterogeneity to take a definitive stance. From a zoomed-out perspective, it can be said that foreign aid may facilitate GDP growth, but only if certain macroeconomic and political conditions are first met – which, in the case of the vast majority of developing countries, is unlikely under current circumstances.

________

[1]Heartiest gratitude to Dr. Nadeem Ul Haque for suggesting and guiding this research. Errors of courtesy remain my own

________

- Historical Backdrop and Political Economy of Foreign Aid

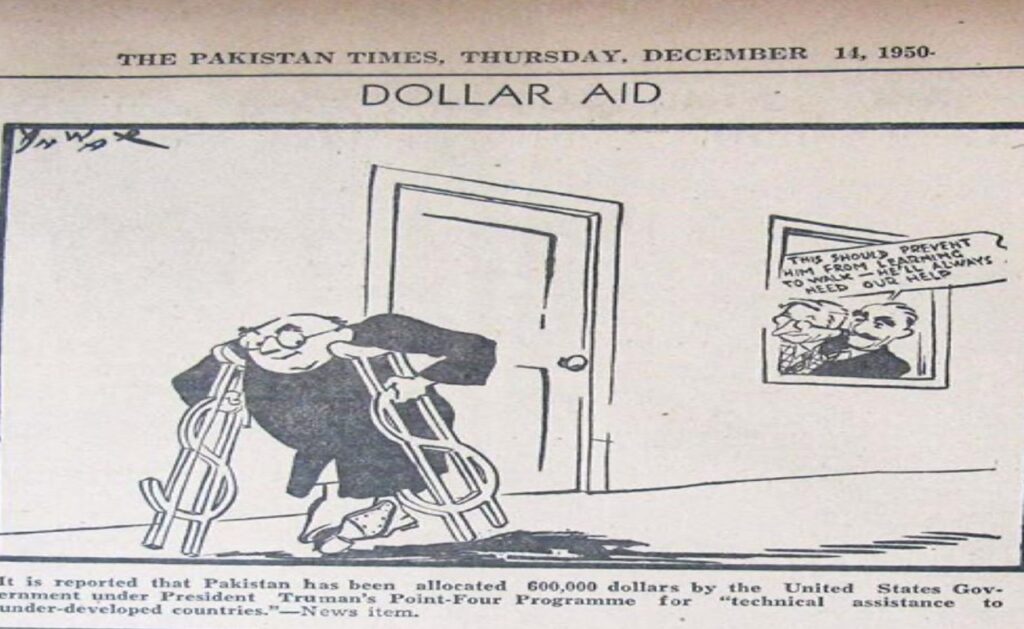

Up until the 20th century, foreign aid largely took the form of military assistance for purposes of conflict and geopolitical manoeuvring. The phenomenon of structured economic assistance to countries began, as per most accounts, with the Marshall Plan of 1948, in which transfers of resources were proposed in an effort to facilitate recovery – particularly in Western Europe – following the turbulence of World War 2. According to some scholars, however, the ‘logic’ of foreign aid – i.e. technocratic, top-down, and largely standardized ‘development’ assistance – began much earlier. William Easterly, for instance, documents that the United States was already involved in this process from 1927 onwards in China: where the Rockefeller Foundation was funding research projects and documenting China’s economic trajectory. (Easterly, 2014)

It is worth pointing out here that the Marshall Plan, besides streamlining assistance for post-war recovery in Europe, also established a series of incentives for these various countries to not ally with the Soviet Union as the Cold War took off in 1945. This is also around the time the United Nations and World Bank were formally established, with the intention of facilitating ‘development’ via loans to low-income countries as part of the agreement during the Bretton Woods Conference a year in 1944.

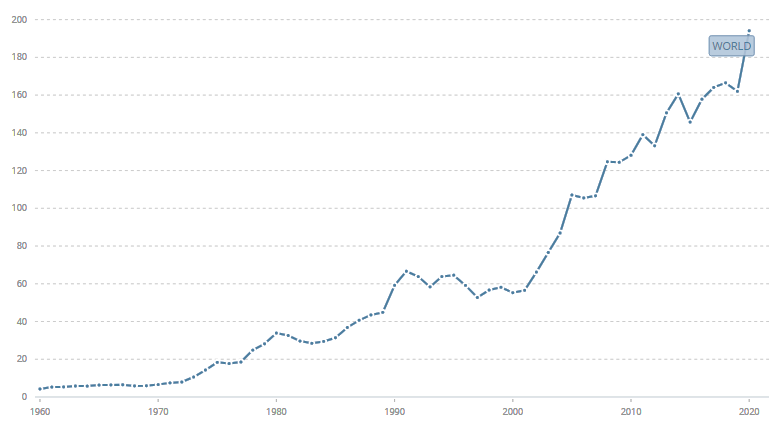

Figure 1. Net Official Development Assistance and Official Aid Received, Global Aggregate in USD Billions

In other words, the political economy of foreign aid is a real arena – and notions of ‘neutrality’ in this particular context are suspect. This is further evidenced by the fact that Britain, for instance, immediately kick-started development projects around the final stages of World War 2 in its own colonies around the globe, particularly in the subcontinent and northern Africa. This is due, as per Easterly, to their having lost credibility during the preceding five years in the eyes of their subjects: who unanimously noted a clear mismatch between the rhetoric of ‘liberty, equality, and fraternity’ hey espoused and their actions during the conflict. In response to this, various ‘development’ projects were initiated in an effort to preserve some form of control over the colonized regions – which lasted a short period before decolonization movements took off around the globe. (Easterly, 2014)

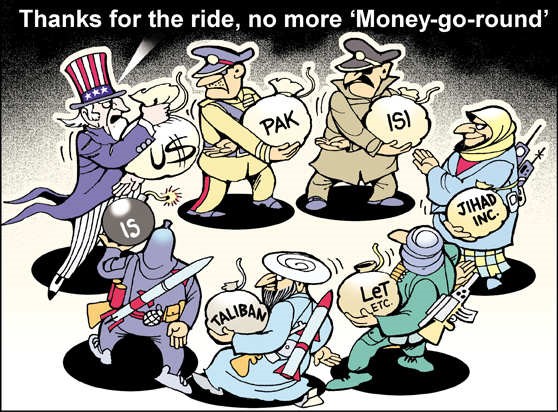

It is worth noting here, as well, that most bilateral aid providers have accepted that aid is a foreign policy tool. Multilaterals lenders such as the IMF and the longer term lenders such as the World Bank, ADB, IMF, etc. are affected by foreign policies of their major shareholders! While the term “aid” is meant to be a benign philanthropic enterprise, especially in Pakistan, we must examine it more carefully. Lenders have also adopted the benign term of “donor” to convey a philanthropic tone which in reality does not exist.

2. The Language and Meaning of Aid

Much of aid is loans though longer term and at concessional interest rates. All aid (grants and loans) comes with strings attached.

- All aid has some form of conditionality. Conditionality is based on the prevailing paradigm in development economics that have been developed in the West. Conditionality can also be based on the foreign policy needs of the major shareholders.

- To determine conditionality, lenders have developed so-called “technical assistance” (TA). Consultants from universities and businesses, therefore, visit Pakistan and other developing countries to study questions they define and give us suggestions for policy. This is in keeping with the orientalist tradition. (Said, 2016). Overtime conditionality has become increasingly intrusive, e.g. by getting into cities’ maternity health, child nutrition, livelihood, and a plethora of other local subjects in the name of development. As Deaton (2015) notes, this intrusive TA erodes governance structures, lacks detailed local knowledge and ownership, and relies on one-size-fits-all.

- Costs of the TA and the conditionality monitoring are hidden in so-called concessional loans and grants, which are significant and makes the loan costly often beyond market rates. (Nadim, 2022)

- TA brings in low quality consultants often to replace the best talent from a poor country, the latter contributing to brain drain. On balance, the country loses talent to build institutions and markets. (Haque and Khan, 2007) (Haque and Aziz, 1998).

- Finally, TA competes with domestic research capacity and is often said to dump on the local research market as it comes bearing gifts. (Haque, 2020).

3. Methodology

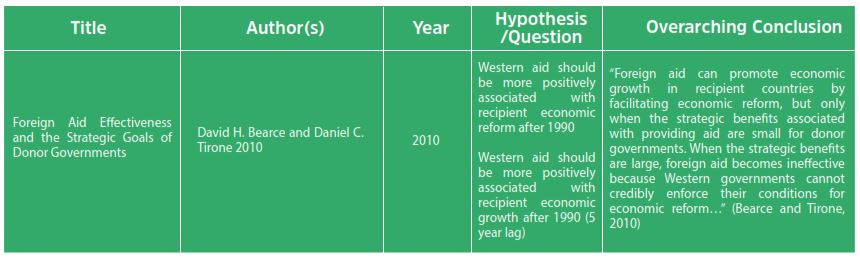

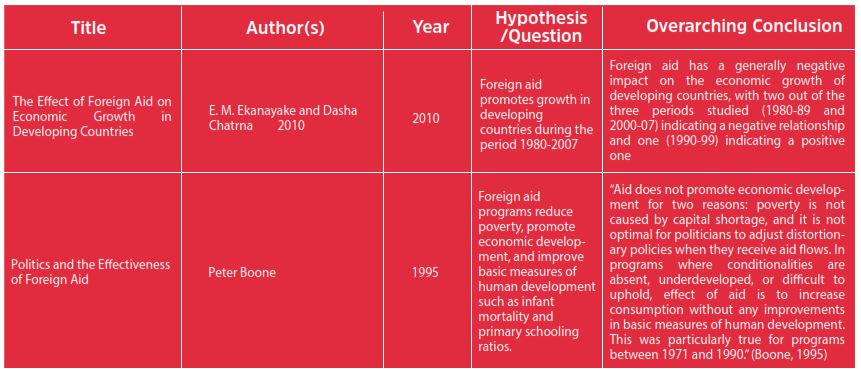

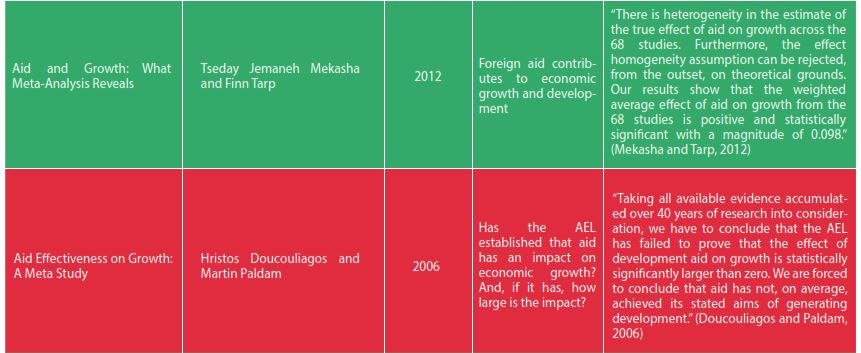

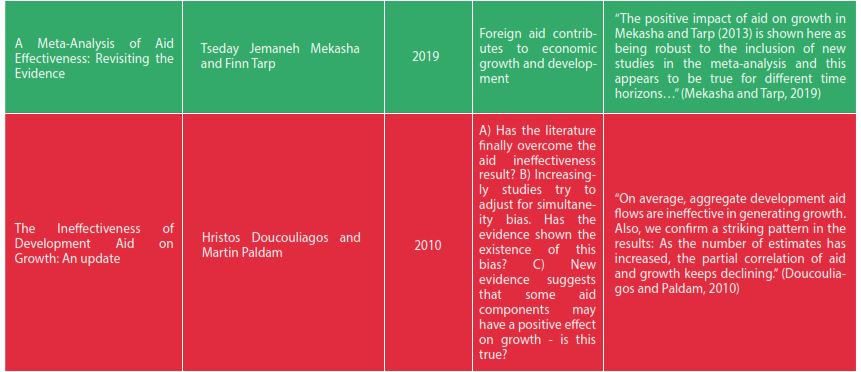

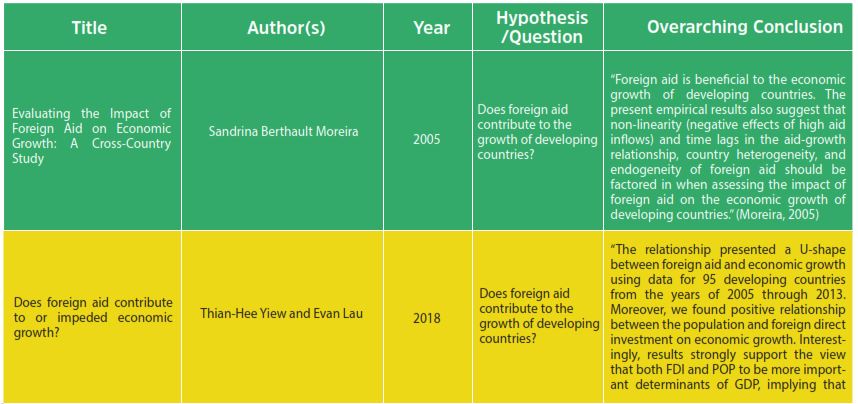

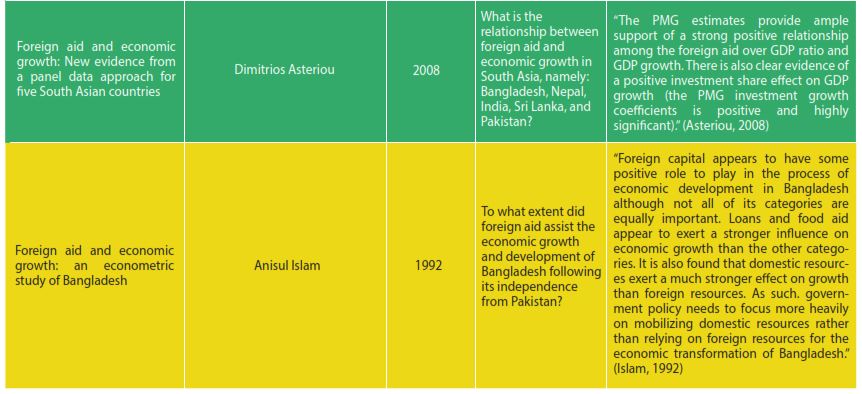

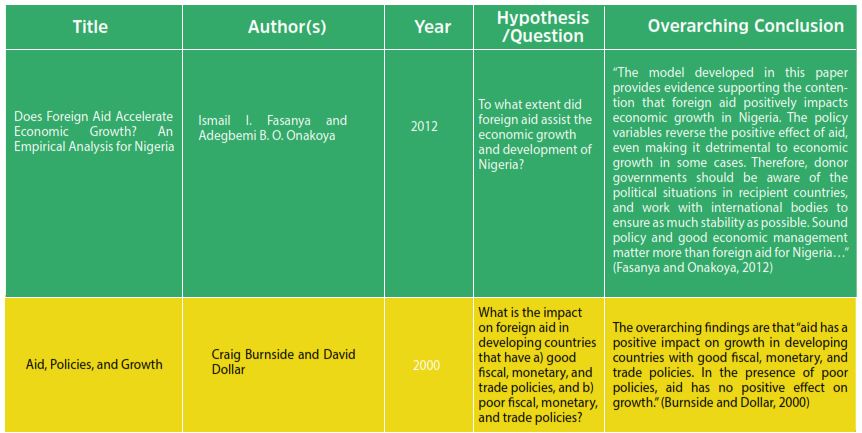

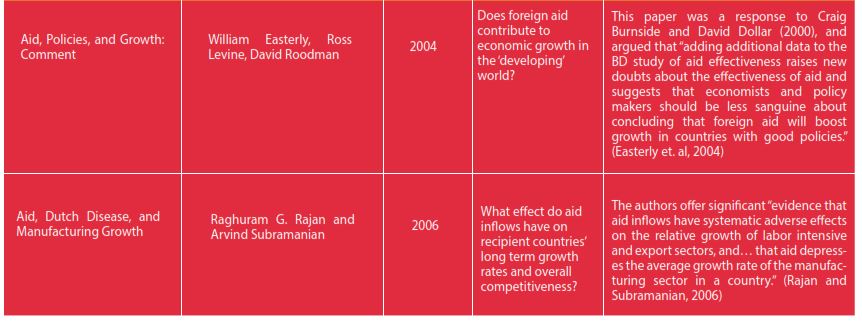

For this brief survey, a comprehensive review of scholarly literature on ‘foreign aid effectiveness’ has been conducted – with a focus on the relationship between aid inflows and economic growth in particular. In order to cover the largest possible sample size, a total of 18 studies – including 4 meta-analyses – were selected for this purpose. Details of author(s), publication year, question/hypothesis, sample, and overarching conclusions are all described.

Studies highlighted in green indicate a positive relationship between aid inflows and economic growth, whereas those in red indicate a negative relationship. On the other hand, those in yellow indicate both – depending on the specific timeline in question and other macroeconomic and political factors. Findings outlined below.

4. Synopsis Matrix of Literature

5. Analysis

Out of the 18 studies in question, 7 reported a negative relationship between foreign aid inflows and economic growth, 8 reported a positive relationship, and 3 reported a mixed relationship.

The mixed relationship that was observed in two of the studies was based on a) the timeline, i.e. negative in the short-run and positive in the long-run, b) a positive relationship observed only in specific forms of aid, i.e. loans and in certain areas, in this case food security, and c) when the macroeconomic policies were ‘good’ – although a clear definition of this was missing. For (b), it was also observed that a comparative analysis of foreign and domestic resource mobilization for purposes of development suggested the latter is much more superior in fostering economic growth and development.

On the other hand, the studies reporting positive relationships largely emphasized certain important caveats to the linkage with economic growth. Some of these were as follows.

- when strategic benefits for the donor were small, meaning initiatives were easy to track/monitor

- when a stable macroeconomic policy environment was present and ensured for future

- when a time lag of approximately 5 years was taken into account

- when the political landscape was generally stable and not prone to turbulence

Among the studies reporting negative relationships, it is worth pointing out that this correlation was not particularly strong – i.e. that aid did not reverse growth by a significant amount in any of the cases studied, but a clear pattern of ineffectiveness was observed. Rajan and Subramanian took the strongest stance against aid in this regard, arguing that it adversely impacts key sectors involved in export markets – including manufacturing, which is generally considered the foundation of healthy economies around the world.

It bears mentioning that some of the studies reporting negative/negligible relationships between aid and growth were of the view that this is due to the evolving nature of development assistance – which has, over time, morphed from narrowly focusing on economic growth (measured by GDP) to broader objectives that revolve around the incubation of social sectors including education, healthcare, livelihood, nutrition, and other thematic areas under the umbrella of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). These are all, however, intimately tied to economic growth – which suggests that this transition away from economic growth and into the social sector may also be largely ineffective, something the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics intends on verifying in future work on the topic of foreign aid.

6. Conclusion

The overarching conclusion from the above synopsis is that foreign aid has had mixed results across the globe, and where these have tilted in the positive direction it has been as a direct consequence of certain factors – outlined above. Therefore, the sweeping claim that there is a direct and positive relationship between aid inflows and economic growth/development is misguided. Aid-flows are increasingly shrinking in relation to the needs of developing countries and market access is increasing for these countries. Moreover, as pointed out above aid flows are not as concessional as claimed as they are loaded with technical assistance and other charges.

It is also worth probing into the effects of foreign aid on sovereignty. Indeed, years of foreign-led aid/development projects and initiatives have functioned to ‘crowd out’ the space for indigenous, context specific research and policy formulation in Pakistan (see Haque 2020). Considering the generally fragile nature of democracy, this has meant an increasing amount of space granted to the interests of external authorities pursuing their narrow, opportunistic interests. As is the case with all policy, this has generated winners and losers – with the vast majority of Pakistan’s population not included at any stage of this elaborate process and experiencing no improvements in their living standards.

According to Friedrich Hayek, the nature of knowledge is always diffuse, extremely context-specific, and largely unarticulated – meaning that top-down initiatives are destined for failure. This has, to be fair, been challenged since the advent of the internet, which revolutionized the production and dissemination of knowledge, but this does not mean it may be substituted for proactive, decentralized, and representative local body governments and, more broadly, institutions that respond to the genuine needs and desires of their constituents. In this regard, a federally administered approach is bound to be ineffective – let alone the initiatives of donor agencies headquartered on the opposite end of the globe. (Hayek, 1945)

William Easterly, in his book titled, ‘The Tyranny of Experts’, elucidates on the above by pinpointing three primary pitfalls in the logic of foreign-led ‘development’ today. First, that it perceives regions/territories as ‘blank slates’ rather than the product of centuries of history. This decontextualized approach is bound to fail as it does not appreciate the fact that every situation is unique, with its own set of norms, cultures, traditions, political dynamics, institutional arrangements, and more – instead relying on a one-size-fits-all strategy. Second, that nations are granted priority over individuals. This means that rather than focusing on how to expand freedoms at the basic human level via the guarantee of fundamental rights such as that of speech, trade, association, assembly, petition, etc., the activities of international financial institutions are based on a ‘tinkering at the margins’ approach that is meant to achieve abstract objectives for nations – such as ‘regional integration’ and ‘curtailing brain drain’. The consequences of this has been a hindering of genuine progress based on individuals having the freedom to self-actualize and contribute to the global economy with their unique talents and skillsets. Finally, foreign aid has from its inception been based on ‘conscious design’ rather than spontaneous solutions. This means that a specific set of prescriptions are meted out to recipient countries, who are asked to implement these – even if it must entail force/violence – in exchange for further aid. Rather than leveraging markets, technology, and people themselves to agglomerate information and adopt an improvisational approach, foreign-led ‘development’ instead relies on textbook solutions that have little to do with the real world, and are thus virtually impossible to truly ‘implement’ and have failed to generate sustainable solutions to pressing socioeconomic ills around the developing world. (Easterly, 2014)

Dambisa Moyo, an African scholar and economist, has elaborated upon the above by outlining the manner in which systemic aid, i.e. led by multilateral donor agencies and international financial institutions, has led to little results in the continent despite over USD 1 trillion being spent over the decades. This, she claims, is the result of absent oversight and involvement from the governments – who have essentially abdicated their responsibilities and granted the NGO sector a virtually free hand in working with and facilitating inroads from various donor agencies in a largely uncritical and opportunistic manner – leading to only short term gains for a small elite that operate in this space. Considering that IFIs generally push large-scale privatization, deregulation, and liberalization, this becomes as a vicious cycle which functions to crowd out space for checks and balances from government agencies, who are told – by ‘experts’ – to not intervene in the free market. On the flip side, interventions from IFIs tend to encourage higher taxation on the SME (small and medium enterprises) sector – the engine of growth via entrepreneurship – primarily because they are easy to control and do not have significant lobbying power like rent-seeking big industrialists might. All this is, of course, assuming that governments here even have the incentive to ‘correct’ this perverse arena, which in the vast majority of Africa they do not – which prompts top bureaucrats to instead involve themselves in the space and appropriate resources via ‘permissions’ and under the table dealings in order to enhance their personal wealth. (Moyo, 2009)

In closing, it is pertinent to emphasize that it is far from self-evident that foreign aid inflows generate economic growth and development – as demonstrated via a holistic assessment of the academic work that has historically been conducted on this phenomenon. Policy makers in Pakistan, therefore, ought to adopt a more context-specific approach that is inwardly focused on structural reform of key institutions in a manner that, first and foremost, incorporates feedback mechanisms that can allow for course correction and informed interventions rather than textbook solutions.

References

Asteriou, D. (2009). Foreign aid and economic growth: New evidence from a panel data approach for five South Asian countries. Journal of policy modeling, 31(1), 155-161.

Bearce, D. H., & Tirone, D. C. (2010). Foreign aid effectiveness and the strategic goals of donor governments. The Journal of Politics, 72(3), 837-851.

Boone, Peter. “Politics and the effectiveness of foreign aid.” European economic review 40.2 (1996): 289-329.

Doucouliagos, H., & Paldam, M. (2008). Aid effectiveness on growth: A meta study. European journal of political economy, 24(1), 1-24.

Doucouliagos, H., & Paldam, M. (2011). The ineffectiveness of development aid on growth: An update. European journal of political economy, 27(2), 399-404.

Durbarry, R., Gemmell, N., & Greenaway, D. (1998). New evidence on the impact of foreign aid on economic growth (No. 98/8). CREDIT Research paper.

Easterly, W. (2014). The tyranny of experts: Economists, dictators, and the forgotten rights of the poor. Basic Books.

Ekanayake, E. M., & Chatrna, D. (2010). The effect of foreign aid on economic growth in developing countries. Journal of International Business and cultural studies, 3, 1.

Fasanya, I. O., & Onakoya, A. B. (2012). Does foreign aid accelerate economic growth? An empirical analysis for Nigeria. International journal of economics and financial issues, 2(4), 423-431.

Gourlay, S., Baffes, J., & Lithgow, D. (2022, August 17). World Bank Open Data. Data. Retrieved August 27, 2022, from https://data.worldbank.org/

Green, M., Harmacek, J., & Htitich, M. (2021). Social Progress Index, 2021: Global index Results. Social Progress Imperative. Retrieved August 30, 2022, from https://www.socialprogress.org

Hague, N. U., & Aziz, J. (1999). The quality of governance:‘second-generation’civil service reform in Africa. Journal of African Economies, 8(suppl_1), 68-106.

Haque, N. U. (2015). Who protects our thought industry.

Hayek, F. A. (1945). The Use of Knowledge in Society. The American Economic Review, 35(4), 519-530.

Islam, A. (1992). Foreign aid and economic growth: an econometric study of Bangladesh. Applied Economics, 24(5), 541-544.

Mekasha, T. J., & Tarp, F. (2013). Aid and growth: What meta-analysis reveals. The journal of development studies, 49(4), 564-583.

Mekasha, T. J., & Tarp, F. (2018). A meta-analysis of aid effectiveness. Revisiting the evidence. United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research (WIDER) Working paper, 44.

Mekasha, T. J., & Tarp, F. (2019). A meta-analysis of aid effectiveness: Revisiting the evidence. Politics and Governance, 7(2), 5-28.

Moreira, S. B. (2005). Evaluating the impact of foreign aid on economic growth: A cross-country study. Journal of Economic Development, 30(2), 25-48.

Nowak‐Lehmann, F., Dreher, A., Herzer, D., Klasen, S., & Martínez‐Zarzoso, I. (2012). Does foreign aid really raise per capita income? A time series perspective. Canadian Journal of Economics/Revue canadienne d’économique, 45(1), 288-313.

Ul Haque, N., & Ali Khan, M. (2007). Institutional Development: Skill Transference Through A Reversal Of ‘Human Capital Flight’Or Technical Assistance. Pacific Economic Review, 12(1), 1-13.

Yiew, T. H., & Lau, E. (2018). Does foreign aid contribute to or impeded economic growth?. Journal of International Studies Vol, 11(3), 21-30.

Said, E. W. (2016). Orientalism. In Social Theory Re-Wired (pp. 402-417). Routledge.

Nadim, H. (2022). Aid, Politics and the War of Narratives in the US-Pakistan Relations: A Case Study of Kerry Lugar Berman Act. Taylor & Francis.

Deaton, A. (2015). On tyrannical experts and expert tyrants. The Review of Austrian Economics, 28(4), 407-412.