Is There an Alternative Path to Foreign Aid?

There has been much talk over the last few years at least—and continues to be—on the failure of the global aid and humanitarian system due to the post-colonial domination of the so-called ‘Global North’ over the so-called ‘Global South’. An overwhelming number of these discussions – which include international donors and NGOs in both geographies – have been framed through the lens of the terms ‘decolonisation of aid’ and ‘localisation of aid’. But this terminology actually avoids confronting the realities and origins of aid – that instead of fostering equity between nations – the desired end-result of any global undertaking – it has instead led to inequity among nations.

The issues we face in global development and humanitarianism today are much bigger than just semantics. They are about how we interpret processes and systems and how we want them to change—or not. They are also about how we contextualise systems and how this context varies based on history, wealth, geography and culture in different parts of the world. Pakistan for instance, has been in debt to foreign aid since soon after its independence. Aid that came from former colonisers in the United Kingdom, Europe and the United States. And continues to do so to this day. Despite our so-called independence as a free state with its own resources, why have we not been able to divorce ourselves from both the cycle of debt that we are spiralling in, as well as from the foreign aid that we accept in the form of bi-lateral and multi-lateral grants and loans?

Current discussions are framing the answer to this question as the on-going influence of colonialism and post colonialism. However, situating the conversation simply within the ambit of colonialism, an extremely complex and historical system, does a disservice to the cause of aid. This is because there is a huge gap between the objectives and modus operandi of the aid system. It can be influenced by colonial undertones of the past, but it can be equally influenced by the present system of global geopolitics, which is far different now than it was after the end of colonialism.

Another way at looking at the failure of aid, is that it is less about the lasting impact of colonialism on post-colonial societies and more about independent nation states that have refused to create self-sufficiency in both financial and human resources to make decisions that benefit their own citizens – Pakistan included. We have allowed power imbalances that control aid to perpetuate, by creating our own internal power imbalances. Power in this case is about wealth inequality not necessarily between the former coloniser and colonised but between state and society.

And even if the global development and humanitarian sectors want to continue to invoke ‘decolonisation’ and ‘localisation’ as a way to bring about change, it is simply one way of seeking global justice. Another way would be to envision a new ‘ecosystem’ which:

- Removes the distinctions between governments, donors, INGOs, NGOs etc. to view all the participants of global development and humanitarianism as ‘state and civil society entities’ or SCSEs. This signifies an amalgamation of the various formal state and non-state organisations, movements, networks, foundations, membership associations, informal groups, citizens/community coalitions etc. that work in the sector – and would be more reflective and inclusive of the changing nature of civic action across the world that we are currently seeing.

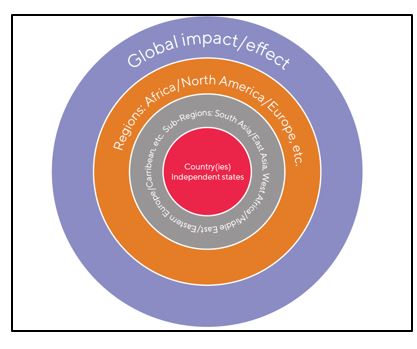

- Removes the distinction between the so-called ‘Global North’ and so-called ‘Global South’ to move to a regional perspective. This advocates for a cooperation framework between regions and regional or national cause-based coalitions/networks, rather than specifically between the ‘Global North’ and ‘Global South’. The term ‘framework’ for ‘international’ cooperation takes the word at its broadest sense and denies this division between ‘North’ and ‘South’ to instead, place countries at the core of change instead of global institutions.

- Removes ‘international’ from the vocabulary and views all countries as equal and global in scale, including taking the ‘I’ out of INGOs to level the playing field. It is imperative that we stop referring to only certain entities as ‘international’ and others as not. Instead, we must encourage the idea of everything being national. There are no ‘international’ entities in this ecosystem because every entity is national by virtue of where it is based and is therefore ‘international’ for every other country.

- Changes and broadens how we see the financial support system by focusing more on the domestic than the international, i.e. allows countries access to a variety of funding sources and mechanisms such as charitable donations, or diaspora contributions, which are less politically motivated than state-based funding from the so-called ‘Global North’ but may have a similar level of resources. But it would also put the onus on countries to broaden areas such as the tax base, domestic entrepreneurship and financial regulations.

Instead of the ‘Global North’ being in the driving seat and the ‘Global South’ trying to ‘shift the power’ towards itself, we must see countries themselves as the core of change. Global impact must emanate from independent states outwards to their immediate neighbours, further out to their geographic regions and then finally, globally. Change must radiate outwards from a core, not inwards towards it.

Cooperation would revolve around regional and national coalitions or networks that would represent particular issues and/or regions with similar interests. Instead of ‘donors’ sitting in headquarters in countries of the so-called ‘Global North’, these coalitions would be based in closer proximity to the location of the cause, e.g. North Africa, or the Caribbean. This would also have the advantage of providing cultural and social compatibility between the financial providers and receivers. Instead of just one form of conventional funding in the form of ‘aid’, there will be many different types of funding available and means by which to access them. Ultimately, the end result would be a more equitable and ethical system which allows each country to participate based on its own ability to make decisions and utilise its own resources as much as possible.

Key ideological shifts required

| From | To |

| ‘Global North’/’Global South’ | Regional |

| International | National |

| Donor funding | Variable funding |

| Eurocentric | Context-specific |

| Project-led | Nation-led |

This is not a perfect system—there is still a stunning amount of wealth, social and political inequality in many countries around the world which will limit the utility of this ecosystem. In Pakistan, we face several challenges to be able to envision such a change; political and religious polarisation, restriction of civil society and social movements, wealth inequality and mismanagement, feudal hierarchies, regional conflicts and failed regional alliances, state apathy and a breakdown of state and civic relations. Just to name a few. How can we even begin to ideologically shift, let alone be willing to wean ourselves off the traditional modalities of aid?

This is by far the biggest challenge in realising this ecosystem; the lack of buy-in of the so-called ‘Global South’, in which there are many countries like Pakistan. How can we convince these countries – who are currently operating not at the behest of their own citizens, but of global geopolitical powers – to have a transparent and safe environment for both state and non-state entities to function domestically and across borders for combined economic and social growth?

The answers are both simple and complex. Simply, they lie in redefining partnerships, resource mobilisation and reimaging our whole political system – domestically. The complexity lies in figuring out how to do that under autocracy and failed democracies, heavily influenced by global geopolitics. But our incapacity to address such mammoth issues, even within our own countries, must not stop us from designing new ways of working and doing. If nothing, we must continue to envision new and alternatives ways of global development and humanitarian aid outside the current conventional form of international assistance. Ultimately, this will take us to ending aid altogether – the most desired outcome of progress and equality.[1]

The author is an independent development professional and an expert on gender, social policy and global migration. She is the co-editor of ‘White Saviorism in International Development: Theories, Practices and Lived Experiences,’ and can be reached via email at [email protected].

[1] This article has been adapted by the author from her latest work; Envisioning an Alternative Ecosystem for Global Development and Humanitarianism; Centre for Humanitarian Leadership, Melbourne (2023)