Misguided Attack on TERF

There have been a lot of discussion of late about the Temporary Economic Refinance Facility (TERF) in WhatsApp groups and talk shows. A member of the Standing Committee on Finance of the National Assembly announced that USD 3 billion was disbursed as interest-free loans during the previous government’s tenure purely on a political bias. Ill thought out allegations such as those on TERF which are politically motivated and illogical not only impede initial investments but also have a detrimental effect on future investment prospects.

Pakistan has been facing a persistent problem of Balance of Payment, as the country lacks sufficient surplus capacity for exporting. To achieve sustainable economic growth in the medium to long term, export-led growth is the only solution. This requires creating the necessary capacity for exporting to overcome the problem and improve the country’s economic prospects. One initiative that aimed to address this issue was the TERF, which provided financing to businesses to increase their exporting capacity. TERF was a laudable scheme that has been replicated globally. Prioritizing initiatives that encourage and support the development of export capabilities is essential for achieving long-term economic growth and stability.

However, it’s important to note that TERF was only available for the import of machinery, and other investments such as land and building costs were not eligible for funding. While TERF was a sizable fund of USD 3 billion, it only covered a portion of the costs involved in expanding exporting capabilities, with other costs estimated at around USD 2 billion. Additionally, some critical machinery is still stuck at ports due to import restrictions, due to non-retirement of LCs. Various factors such as energy issues, liquidity crises, high policy rates, and a challenging business environment for industrialists have hampered the project’s success. Therefore, attacking the TERF scheme may not benefit anyone, as none of the industrialists have gained benefit, given the many challenges and limitations involved in actually implementing it. The very purpose of the expanded capacity has been defeated in the process.

Central banks around the world have had launched or reinstated funding-for-lending programs to provide credit to the non-financial sector as a response to the pandemic. Examples include the Central Bank of Brazil’s ‘Working Capital for Business Continuity’ program and the European Central Bank’s provision of over 1 trillion Euros to commercial banks for credit facilities. The State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) has also launched its own concessionary refinance facility, the TERF, which provided liquidity to help businesses combat economic implications due to COVID-19. The TERF aimed to help businesses and industries stay afloat during the pandemic, protect jobs, and stimulate economic growth. TERF has led to an increase in economic activity and created jobs. This can be supported by the fact that, according to PBS’s Labour Force Survey 2020-21 annual report, the number of employed people rose by 3.22 million, from 64.03 million in 2018-19 to 67.25 million in 2020-21. This indicates an annual addition of 1.61 million people to the employed workforce since the scheme was announced on March 17, 2020.

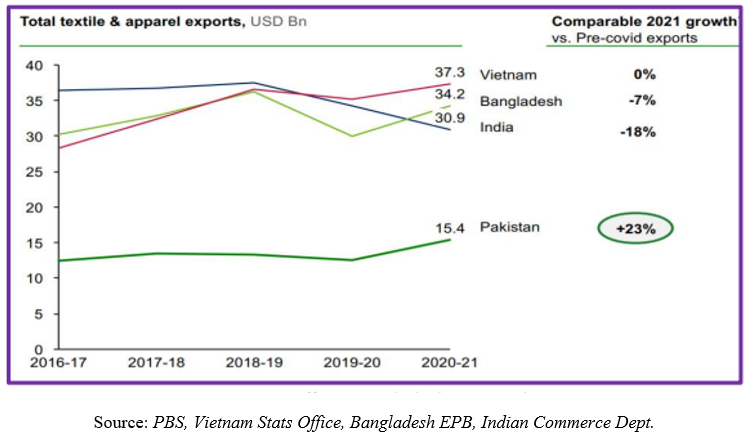

The government’s proactive approach in introducing the TERF was correct and demonstrated its commitment to supporting the industry and laying the foundation for sustainable economic recovery during the pandemic. Despite this, misinformation is being spread about the program. The TERF has been instrumental in laying the groundwork for significant increases in exports and industrial expansion, and it is widely considered a brilliant step taken by the SBP. The trade figures show a clear upward trend in the growth rate of the textile exports over the past few years. In the fiscal year 2020, the textile exports stood at USD 12.5 billion, which is a relatively moderate rate owing to the onset of COVID. However, the textile exports in the fiscal year FY21 increased to USD 15.4 billion, indicating a considerable improvement in the overall economic performance of the country. The trend continued for FY22 as well whereby the textile export figure equalled USD 19.4 billion – an increase of 55% in just two years. TERF has played an instrumental role in this.

The eligibility criteria for the TERF scheme were not limited to large industrial units only, but also included small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). In fact, according to the SBP, the scheme was designed to provide support to all types of businesses affected by the pandemic, including micro-enterprises, SMEs, and large corporations.

There is a proposition that the TERF program led to a surge in investment, causing an increase in demand for imported machinery, which in turn triggered a current account deficit. However, this argument overlooks the fact that the pandemic had already caused a significant reduction in imports due to reduced economic activity. The increase in demand for imported machinery was a result of the recovery in economic activity, which was also a positive outcome of the program. One billion dollars of imported machinery can generate over 1.5 billion dollars of exports each year, making the trade-off very clear and in favour of importing machinery. It is unclear why the basis for capacity enhancement, which is machinery imports, is being portrayed negatively.

It is being implied that TERF did not generate significant exports. However, this claim is not supported by any data. In fact, an op-ed article, published this week against TERF, itself estimates that the scheme could have generated annual exports in excess of USD 6 billion per annum once all projects were operational. One of the most critical points that is often overlooked is that while some investments have been made in Pakistan through TERF, its partial impact was only seen in the fiscal year 2021-22 as explained above. It is important to recognise that although Pakistan’s export growth has been impressive, it is not continuing at the same pace for a few reasons. One of the reasons is the opening restrictions on L/Cs. Additionally, the failure of the cotton crop and the availability and pricing of energy pose significant challenges, which immediately put Pakistan’s exports at a competitive disadvantage.

The country has been facing challenges related to energy supply, with frequent power outages and load shedding causing significant disruptions to businesses and households. These energy issues have a direct impact on the productivity of the workforce and discourage foreign investment, which is crucial for sustained economic growth.

Pakistan has been facing a rising import bill, with a significant amount of foreign exchange reserves being spent on essential goods. This has resulted in a trade deficit, which has further strained the country’s economy. The TERF scheme was implemented to help address this issue by replacing outdated industrial machinery with newer, more modern equipment to increase production capacity. However, the delivery timelines for the imported machinery were affected by supply chain disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, Pakistan’s economic conditions have continued to deteriorate, and import restrictions have further hindered the import of machinery ordered under the TERF scheme. As a result, the expected growth rate was not achieved. Nevertheless, there is hope that once the import and energy issues are resolved, the imported machinery will help to revitalize the economy on a sustainable export led growth basis.

It is essential to recognise the multiplier effects of value addition, as a single textile unit can create up to 5,000 jobs, and the establishment of a hundred units can potentially create up to 500,000 new jobs. This investment has been instrumental in enhancing productivity in the textile sector, from spinning to stitching. In addition, capacity utilization and price increases in international markets have helped to increase textile exports. This USD 5 billion investment in 2021 by the textile sector through TERF and LTFF programs has brought about tremendous opportunities for growth and development in the sector, adding to the export potential by at least USD 5 billion per annum.

As a direct result of this investment, the sector has significantly expanded its production capacity, with 1.25 million spindles, 6,000 air jet looms, and 3 million square meters of fabric being installed. These new investments have enabled the textile sector to produce a wide range of high-quality textiles, from yarn to finished fabrics, to meet the growing demand of international markets.

The investments made by TERF/LTFF in the textile sector have had a significant impact on Pakistan’s economy by providing new employment opportunities, increasing exports, and boosting the country’s GDP. This has also helped the country to improve its trade balance and reduce its reliance on imports. The investment in the textile sector through TERF/LTFF has been a game-changer for Pakistan’s economy, enabling the country to strengthen its position in the global textile market and further enhance its reputation as a leading textile producer. The textile sector is a significant contributor to the global economy, and this investment is expected to have a positive impact on Pakistan’s economy.

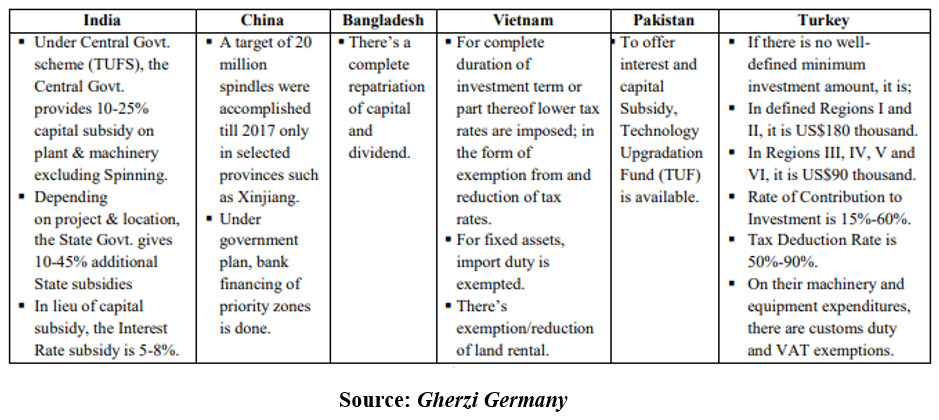

It is also worth noting that there are significant differences in investment subsidies among various Asian countries, as illustrated in the table below. In Pakistan, only direct exporters are subject to a 1% liability tax, while indirect exporters, who comprise 70-80% of the supply chain, must pay all taxes in full.

Investment Subsidies: Regional Comparison

During the pandemic-induced financial crisis, central banks used traditional tools but with greater speed and scope than in past crises. They cut interest rates, created lending programs, and changed financial regulations to support businesses and reduce long-term economic damage. However, economists warned that the quick increase in the money supply and debt accumulation could lead to stagflation. The SBP responded quickly with measures such as lowering policy interest rates and offering loan extensions and employment protection schemes to mitigate the economic consequences of the pandemic. Overall, the monetary policy response has significantly contributed to reducing potential long-term harm to economies and financial systems.

Pakistan’s government support schemes for exporters are necessary to keep the industry competitive with regional competitors. The supportive policies, including competitive energy, have enabled the industry to attract investment and expand its capacity and technological capabilities. However, systemic inefficiencies, administrative delays, and the high cost of doing business have contributed to an unsustainable business environment. The private sector’s ability to stimulate economic development has been limited due to the high interest rate. Textile exports were growing consistently and persistently, but hindrance to its operations have now led to a drop in exports leading to a failing economy, increased unemployment, and the need to borrow from the IMF. Supporting export-led growth is crucial for sustaining Pakistan’s economic and political sovereignty, and any attacks on the industry may be motivated to undermine its operations and discourage investments. It is important for all parties to avoid making attacks and arguments that can have a catastrophic effect on the economic and political sustainability and sovereignty of Pakistan. This is necessary if Pakistan is to look towards a brighter future.

The author is an industrialist, entrepreneur, and philanthropist. He is currently serving as the Patron-in-Chief of the All Pakistan Textile Mills Association (APTMA).