Pre-Afghan Taliban Refugee Exodus and the Complexities of Returning Home

Overview:

This study is designed to address some key questions regarding Afghan refugee’s exodus. Such as, when did Afghan refugees migrate to Pakistan? What are the prominent factors which compiled Afghan Refugees to flee Afghanistan? What they deem about the future destination? Are they willing to repatriate to Afghanistan? why/why not? In the first step, this study has discussed the recent Afghan repatriation policy of the caretaker government, and identified either the Afghan refugee’s migration was voluntary or involuntary, similarly is the repatriation forced or voluntary? Moreover, this study provides a brief history of Afghan refugee’s migration. In the second part, this study has empirically, addressed the eminent questions. And finally, suggest policy proposal regarding sustainable repatriation of Afghans to Afghanistan.

Deportation of Afghan Citizens.

Pakistan is among the largest refugees hosting-countries, hosting Afghan refugees since four decades. In fact, the second and third generation of Afghans are living in Pakistan. According to UNHCR’s recent report there are around 3 million Afghan refugees living in Pakistan and additional 0.7 million sought refuge since the fall of Kabul and Taliban takeover. The Afghans have different legal status including Proof of Registration (PoR) cardholders, Afghan Citizen Card (ACC) holders, undocumented, in irregular status, or holding an ordinary visa (student, work, medical, marriage etc) (ADSO, 2023). However, the government of Pakistan has categorized the recent arrivals in three different categories such as,

- Temporary migrants (those residing in border towns, with extended families, or camps)

- Transit refugees (those arrived based on the reasons of being settled in other countries)

- Resident Card Holders

____________

I express my sincere appreciation to, Dr.Durr-e-Nayab, Dr.Nasir Iqbal and Shahid Mahmood for their invaluable support and guidance.

____________

The caretaker government of Pakistan, through Ministry of Interior, on 26 September 2023 issued the ‘Illegal Foreigners Repatriation Plan’. According to the proposed plan, the intension is to regulate the presence of foreigners in Pakistan, and to deport the illegal ones to their country of origin. In fact, the deportation plan of foreigners was implemented by the caretaker government, which speculated that illegal immigrants were involved in suicide attacks and contributed to lamentable economic situation Although there is a considerable number of immigrants living in Pakistan, the Illegal Foreigners Repatriation Plan primarily targets Afghan nationals. In fact, the government is committed to deport all the refugees/foreigners irrespective of their legal status. The planned repatriation would be in three different waves (ADSP, 2023), which are as follows:

- In the first phase all illegal or unregistered foreigner and those and those who have overstayed their visa validity periods would be deported

- In the second phase, Afghans holding Afghan Citizen Cards (ACC) will be repatriated to Afghanistan.

- And, finally, Proof of Registration (PoR) card holders will be deported to their country of origin

Consequently, Afghans have voluntarily or involuntarily responded by returning to Afghanistan. In fact, the rate of Afghans return is above the average return rate. Between 15 September and 21 October this year, 83,268 Afghans returned through the Torkham and Chaman border crossing points to Afghanistan. (UNHCR-IOM, 2023).

Dilemma of Involuntary Migration and Repatriation:

The word Migration is taken from the Latin word “migrata”,s which mean to change one’s place of residence. Migration is generally defined, as the temporary or permanent change in residence, a movement of people from one place (the place of origin) to another (place of destination) for a better life, more income, good food supply and additionally to get refuge from instability, conflict and natural disasters (Vargas-Lundius et al., 2008).

There are two forms of migration, voluntary and involuntary or forced migration. The voluntary migration refers to the movement of people from one place (place of origin) to another (place of destination) by their will. On the other hand, forced migration refers to the migration when people move from their countries (place of origin) to escape from persecution, conflicts, repression, natural or man-made disasters, ecological degradation or other situation that endanger their lives and freedom or livelihood ((Wickramasekera, 2002; IOM: United Nations 2000). In fact, the 1951 Convention of UNHCR defines a Refugee as “Someone who is impotent or reluctant to return to their homeland because of well-founded fear of being ill-treated owing to his/her race, religion, nationality, or owing to any affiliation with social or political groups”. The Afghan refugees mainly migrated involuntarily from Afghanistan to the neighboring countries to escape from war, persecution, religious extremism and ongoing conflicts in Afghanistan.

There are two types of repatriations, voluntary and involuntary. The voluntary repatriation refers to a free and unhampered decision of refugees to return to their country of origin. On the other hand, involuntary repatriation refers to the return of refugees to their country of origin without their free consent or choice. This study and existing literature show that likewise the Afghans migration, repatriation of Afghan nationals is also involuntary due to the reluctance of majority to return to Afghanistan. This study shows that majority (67.3%) of the Afghan national are not willing to return to Afghanistan. Moreover, evidence suggests that many refuges have been pressured to leave Pakistan despite the unsafe and unfavorable conditions in Afghanistan (Hiegemann, 2014). Recent reports from returnees highlight that a significant 87% cited the fear of arrest as the primary motivation for returning to Afghanistan (UNHCR-IOM, 2023). Just as they initially fled to escape persecution, the persisting fear of persecution now coerces them to return to their home country.

Brief History of Afghan Refugees Exodus:

Historically, there has always been movement of individuals and groups across Pak-Afghan border, primarily owing to presence of same ethno-linguistic groups on both sides of border. It remained a “buffer zone” under British rule, an area demarcated as the territory under British influence in order to deter Afghan and Russian invasion. And, it remained outside of full grip of Pakistani Constitution and laws until March 2018 when the former FATA agencies were merged into the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) under the 25th Amendment. The movement across the border proved difficult to regulate. Yet the inflow and outflow across the border was limited between 1947-1970. In fact, influx of Afghan refugees picked up pace since 1970s when her political situations changed. Since then, Afghans have experienced different phase of massive displacement. Majority of them migrated to Pakistan and Iran in order to escape from war, persecution, religious extremism and conflicts. We can categorize the refugees’ massive inflow in four waves and four major developments in Afghanistan, which compelled the Afghans to flee Afghanistan.

First Wave; (End of Daoud’s Government and Soviet Union Invasion) The first major wave of Afghan refugees began between 1978-1981, when Marxists Peoples Democratic Part of Afghanistan (PDPA) overthrown government of Muhammad Daoud , and later accelerated with Soviet Union invasion in 1979 (Kakar, 1997) . Consequently, by the beginning of 1981, some 3.7 million refugees had fled to Iran and Pakistan (Turton & Marsden, 2002).

Second Wave; (Withdrawal of Soviet Union and Re-emergence of Mujahedeen) The second wave was with the withdrawal of Soviet Union and re-emergence of Taliban, which gave birth to civil war in Afghanistan. And, Mujahedeen forced PDPA out of power in 1992, and persecuted PDAP civil servants (Rashid, 2010). The result was a new wave of immigrants to Pakistan.

Third Wave; (The 9/11 attack and US-led Invasion) The third wave of refugees numbering 200,000 to 300,000 left Afghanistan during the U.S.-led invasion of October 2001, (Margesson, 2007).

Fourth Wave; (withdrawal of US and the fall of Kabul to Taliban) A final wave of refugees began on August 15, 2021, when the Taliban overthrew Ashraf Ghani’s government and seized power in Afghanistan

Data and Demographic Characteristics:

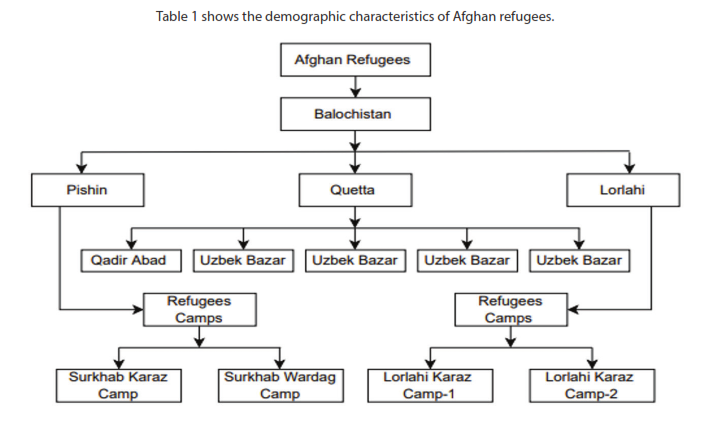

For this study we are using data collected from 300 Afghan household residing in three major districts of Balochistan, (Quetta, Pishin and Lorlahi), through household survey. In fact, it covers different areas where the refugees are living. And, in district Pishin the data was collected from refugee camp (Surkhab Afghan Refugees camp). Moreover, in district Lorlahi we have conducted household survey in two different refugees’ camps (Karaz camp 1 and Karaz camp 2). In district Quetta, different areas were visited where Afghan refugees resides. The locale of the study is depicted in the flowchart given below.

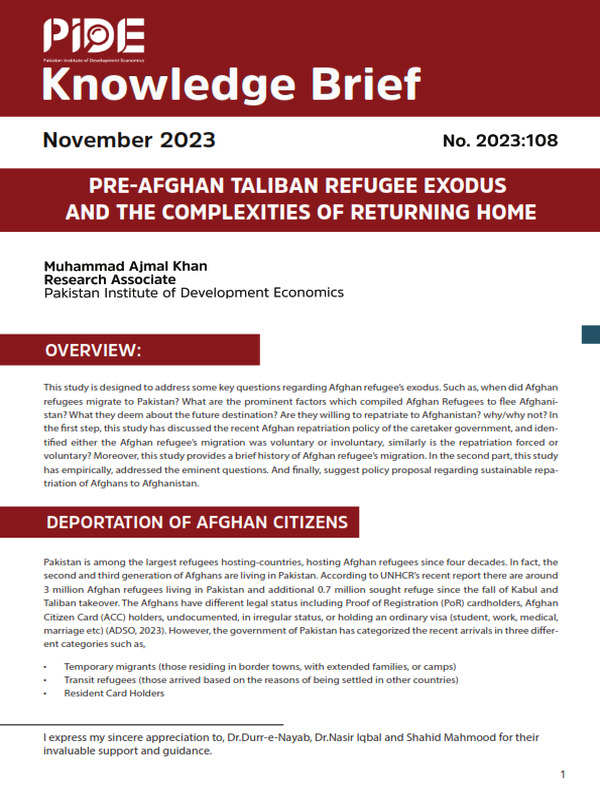

Table 1: Demographic Characteristics of Afghan Refugees

Table 1: Demographic Characteristics of Afghan Refugees

Study Findings;

This section of the study elaborates the survey findings such as the Afghan refugees’ years of migration, the factors which compiled them to flee Afghanistan, their future destination and highlights the primary reason for not returning to Afghanistan. and, finally suggest some policy proposal for a sustainable repatriation of Afghans.

Afghan Refugees Migration waves

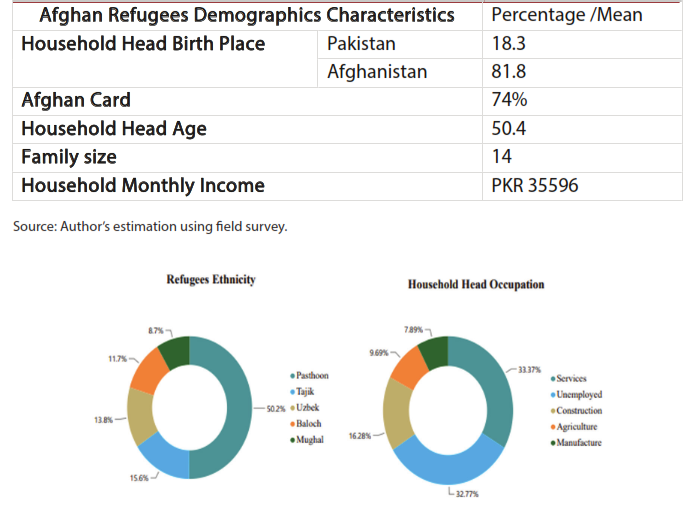

The figure 1 shows the Afghan refugees’ years of migration to Pakistan. Data revels that

- Afghans began fleeing their country in 1960. In fact, 3.2% of Afghans reported that they came to Pakistan between 1960-1975

- Almost half of the Afghan refugees living in Balochistan reported that they fled Afghanistan between 1976-1980. This reflects the first massive wave of Afghan refugees.

- Moreover, the data shows that the second largest exodus was recorded between 1981 and 1985, (28.6%) followed by the migration since 1991 (16.4%).

- To sum up, we can categories the pre-Afghan Taliban regime exodus in three waves, which has close link with major developments in Afghanistan. Such as the first wave in 1979, when Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan, the second wave was the end of Soviet Union and emergence of civil war in the country (reemergence of Mujahedeen) and, finally third wave of Afghan refugees during U.S-led invasion after the 9/11 attack. These findings are in line with (Turton & Marsden, n.d.2002) and (Margesson, 2007).

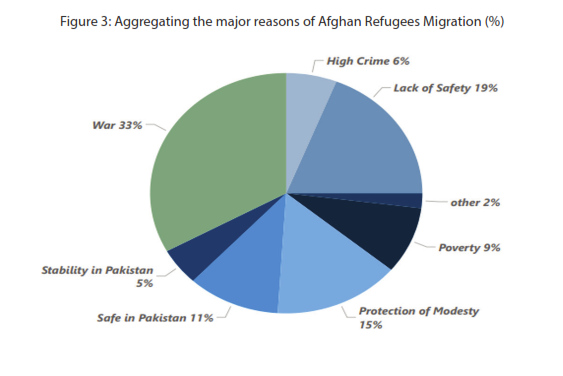

Key Factors that forced Afghans to flee Afghanistan:

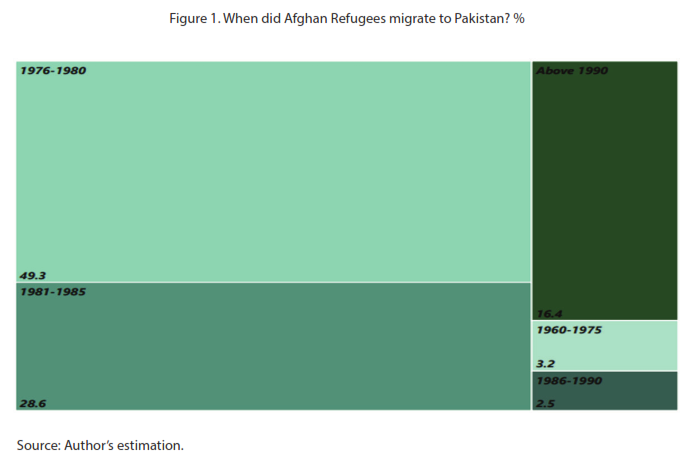

The first question that come to one’s mind while investigating the refugees or Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) is that, why do individuals move from one place to another place? In fact, this section seeks to answer the primary question that, what are the prominent factors which lead Afghan to flee their country? In fact, the respondents have reveled both the push and pull factors of migration. The responses are depicted in figure 2, and shows that

- Among the push factors, 97.1% of the respondents cited war, lack of safety (56.8%), protection of modesty (44.3%) and the poverty (26.8%) which compiled them to flee their country.

- And, among the pull factors, 31.8% reported the feeling of safety in Pakistan followed by stability in Pakistan (15%).

What Afghans deem about the future destination?

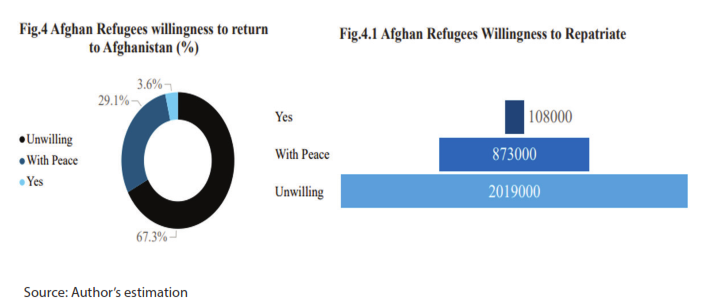

Figure 4 shows the Afghan refugees’ willingness to repatriate to their country of origin (Afghanistan). In fact, the findings show that majority of Afghan refugees are not willing to repatriate. As per the recent UNHCR report there are around 3.7 million Afghans in Pakistan, among them some 700,000 Afghans who fled to Pakistan after the Taliban takeover on August 15, 2021. However, this study includes the perceptions of Afghans who fled to Pakistan before the Taliban takeover. Thus, the figure 4 reveals Afghans’ willingness to return to their country of origin in percentage. And, on the other hand, figure 4.1 shows the estimated number of Afghan refugees’ willingness to repatriate to Afghanistan based on the findings of this study, assuming the total population of 3 million Afghans. Thus, we can summarize their willingness as follows.

- Majority (67.3%) of Afghan refugees are not willing to return to Afghanistan.

- On the other hand, approximately 4% were willing to repatriate to Afghanistan.

- However, around 29% cited that “yes we are willing to move to country of origin (Afghanistan), but with (condition) return of peace and security in Afghanistan”.

- To sum up, majority of the refugees are settled in Pakistan are not willing to repatriate and major portion has associated their return with peace and stability in home town. Thus, stability in Afghanistan in indispensable for the Afghans voluntary reputation process.

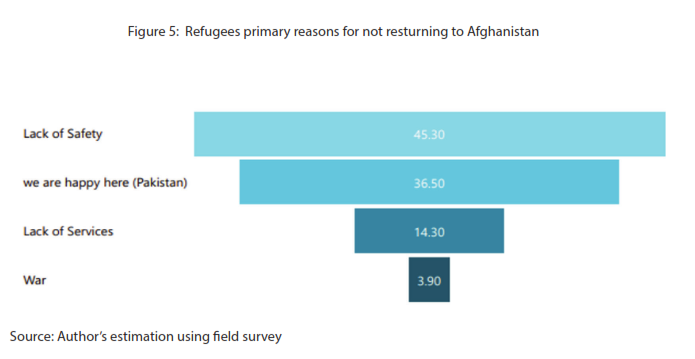

Afghan Refugees’ Reluctance to Repatriate;

The majority of Afghan citizens are reluctant to repatriate to Afghanistan. They have also reported the reasons behind this behavior. Figure 5 shows the primary reasons Afghans are not returning to their country of origin. The findings reveal that

- Majority of Afghan refugees reported the lack of safety as primary reason for not returning to their home country (Afghanistan).

- And, around 36.5% of Afghan refugees residing in Balochistan, reported that they are happy in Pakistan, therefore they are not willing to move back to their hometown.

- Moreover, 14.3% of refugees reported the lack of services in Afghanistan, and approximately 4% reported the persistence of war as main reason for their stay in Pakistan.

Recommendations:

This study shows, only 4% of Afghan refugees are voluntarily willing to repatriate to Afghanistan, while 29.1% are willing to return to their country of origin with condition of peace in home country (Afghanistan). The remaining 67.3% are not willing to move to Afghanistan at all! Although Afghanistan is comparatively in a state of peace since Taliban takeover, refugees don’t feel comfortable returning to Afghanistan under their rule. This implies that the repatriation of Afghan refugees would be involuntary which is against the customs of international law, principle of non-refoulement, despite Pakistan neither ratifying the 1951 Convention nor 1967 Protocol related to the status of refugees.

The government of Pakistan on the other hand is committed to force out all Afghans and other foreign nationals living unlawfully in the country. In fact, Pakistan’s Interior Minister stated that all undocumented Afghans must leave the country by 1 November 2023. Those who fail to do so will face deportation. “If they do not go…then all the law enforcement agencies in the provinces or federal government will be utilized to deport them”. Sources claim that the stringent policy owing to the involvement of Afghan individuals in acts of the terror in the country (14 out of 24). Additionally, entertaining around 3.7 million refugees is proving to be an additional burden on the state and the resources. But the question is, will the Afghan refugees return to their home country? And, what is the probability of their voluntary repatriation? And, would it be possible for the refugees to return immediately? Is the deadline for return appropriate for their return? Will the refugees be in a position to liquidate their assets within a short time period? And, what would be the response of local political parties? Would the Taliban government welcome them? Moreover, are they in position to facilitate these returnees considering the difficult situation of the Afghan economy? Has the caretaker government considered the costs and benefits of hosting and repatriating Afghans?

Based on the findings of this study and considering the dynamics of Afghan refugees requires a comprehensive and sensitive approach that takes into account their concerns and ensures their voluntary repatriation, in compliance with international laws and standards. Here is a suggested strategy for Afghan refugees’ sustainable repatriation policy to be consider by the government and relevant stake holders in Pakistan for their repatriation to Afghanistan.

Cost Benefit Analysis:

Unfortunately, there is no research on the cost and benefits associated with hosting Afghan refugees in Pakistan, except for a few minor attempts that shows the social and political cost of Afghan refugees (Borthakur, 2017).In reality, these refugees have both costs and benefits in all aspect of life be it social, economic or political, although, the common perception is that Afghans are burden on the economy of Pakistan and, it’s that it’s difficult for Pakistan to accommodate the impoverished population.

The Afghans living for more than 4 decades have benefits as well, which are not realized yet. In fact, the influx of Afghan refugees has made a significant impact on the agricultural sector at the provincial level. They have not only transformed the agricultural landscape in Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) but have also served as a vital labor force in the challenging field of mining, a job many local residents tend to avoid. Additionally, their investments in the country have led to the establishment of businesses, directly contributing to economic growth. Moreover, as consumers, they play a role in stimulating various sectors of the economy. Aid to refugees creates significant positive income spillovers to host-country businesses and households (Taylor et al., 2016). Recognizing these contributions, the government should consider the benefits brought by these refugees and acknowledge their positive influence on the nation’s development. Thus, the government should take a well inform decision based on the cost and benefits associated both with the presence and repatriation of Afghan refugees considering the all aspects such as, social, political, economic. And, considering these factors become more relevant when the returnees home country is neighboring country.

Repatriation Deadline:

The deadline set by the caretaker government is insufficient for the refugees to return to their home country, even if they are all willing to repatriate voluntarily. In fact, a large number of these refugees have been residing in Pakistan for more than four decades. They are fully settled here and are entitled to various assets. Thus, the one-month ultimatum is inadequate for the refugees to liquidate their assets. Therefore, the government should provide ample time for the refugees to sell their valuable or immovable assets. We recommend a period of at least 1 to 2 years if the government is committed to repatriating out all Afghans.

Repatriation in phases/waves:

The Afghans influx was in four major flows at different time and developments in their home country. Similarly, their repatriation should also be in form of gradual waves rather than a single ultimatum. The disaggregation, in turn, might be based on the area zones, such as, targeting urban setting followed by the refugees’ camps. Or might initiate a repatriation process at districts levels for the smooth transition to Afghanistan.

Ensure Voluntary Repatriation;

As the influx of refugees to Pakistan was involuntary, and it seems the outflow would also be involuntary, which goes against customary international law and the principle of non-refoulement. Therefore, the government should ensure the voluntary migration of Afghan refugees rather than a forceful one.

Compliance with International Standards Humanitarian Aspect;

Additionally, the government should come up with comprehensive strategy which ensures their voluntary repatriation, in compliance with international laws and standards. And, considering the humanitarian aspect of their repatriation

Collaboration with stakeholders:

The caretaker government should have initiated the Afghan repatriation policy in collaboration with stakeholders, including political parties, social activists, humanitarian agencies, NGOs, the caretaker Afghan government, and refugee representatives

Border Management and Registration:

Finally, we recommend border management and registration of individuals crossing the border from both sides. Additionally, since border management might cause joblessness among local residents, the provincial government should have an alternative plan for those affected

Conclusion:

Based on the finding of this study, we can categories the pre–Afghan Taliban regimes, exodus in three waves, which have close link with major developments in Afghanistan. Such as the first wave in 1979, when Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan, the second wave was outcome of the end of Soviet Union and emergence of civil war in the country (reemergence of Mujahedeen) and, finally third wave of Afghan refugees during U.S-led invasion after the 9/11 attack. Both the push and full factors compiled Afghans to flee Afghanistan. Among push factors, the prominent factors include war (97.1%), lack of safety (56.8%), protection of modesty (44.3%) and the poverty (26.8%). On the other hand, pull factors include the feeling of safety in Pakistan (31.8%) followed by stability in Pakistan (15%). Moreover, this study reveals that majority (67%) of pre-Afghan Taliban regime refugees are not willing to repatriate to Afghanistan, owing to, the lack of safety, services and their desire of being happy in Pakistan. The motivational force behind Afghan refugee’s exodus to Pakistan is political rather than economic in nature, they escaped the unstable Afghanistan and majority of the refugees feels that they are safe in Pakistan. Moreover, they are not willing to repatriate to Afghanistan in presence of political instability. Additionally, the findings indicates that both the Afghan national’s migration and repatriation is involuntary. Thus, based on the findings of this study and considering the dynamics of Afghan refugees in Pakistan, requires a comprehensive and sensitive approach that takes into account their concerns and ensures their voluntary repatriation, in compliance with international laws and standards.

References:

ADSP. (2023). ADSP Briefing Note: Deported to what? Afghans in Pakistan – October 2023 – Pakistan | ReliefWeb. https://reliefweb.int/report/pakistan/adsp-briefing-note-deported-what-afghans-pakistan-october-2023

Borthakur, A. (2017). Afghan Refugees: The Impact on Pakistan. Asian Affairs, 48(3), 488–509. https://doi.org/10.1080/03068374.2017.1362871

Hiegemann, V. (2014). Repatriation of Afghan Refugees in Pakistan: Voluntary. Oxford Monitor of Forced Migration, 4(1), 1–4.

Kakar, M. H. (1997). The Soviet Invasion and the Afghan Response, 1979–1982. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Margesson, R. (2007). Afghan refugees: Current status and future prospects.

Rashid, A. (2010). Taliban: Militant Islam, oil and fundamentalism in Central Asia. Yale University Press.

Taylor, J. E., Filipski, M. J., Alloush, M., Gupta, A., Rojas Valdes, R. I., & Gonzalez-Estrada, E. (2016). Economic impact of refugees. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(27), 7449–7453. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1604566113

Turton, D., & Marsden, P. (n.d.). Taking Refugees for a Ride? 70.

Turton, D., & Marsden, P. R. V. (2002). Taking refugees for a ride?: The politics of refugee return to Afghanistan. Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU).

UNHCR-IOM. (2023). UNHCR-IOM Pakistan Flash update 2 on Arrest and Detention/Flow Monitoring, 15 Sep to 21 Oct 2023. UNHCR Operational Data Portal (ODP). https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/104254

Vargas-Lundius, R., Lanly, G., Villarreal, M., & Osorio, M. (2008). International migration, remittances and rural development.

Wickramasekera, P. (2002). Asian labour migration: Issues and challenges in an era of globalization: International Migration Programme. International Labour Office: Geneva.