Psychogeographical Deceit; State-esque Narratology

Though by mid-2023, peoples of the world have had ample time to question nation-states and their resultant animosities against the larger human endeavor, but the idea of a country and the formation of such an idea is always a work in progress. A state of movement being integral to everything humanist, forming political understanding is also a non-linear process of education that preferably is a work of a lifetime. ‘What is a country?’ can be an existential question but making things simpler, ‘what is Pakistan?’ cannot have an absolutist answer. The larger human endeavor connotes the eventual stipulation that all humanity is bound by a certain love of Mother Earth and ultimately seeks such an unhinged love to progress through life; all progress is not necessarily capitalist. The larger human endeavor also somehow stipulates that one must know, if anything one’s own country.

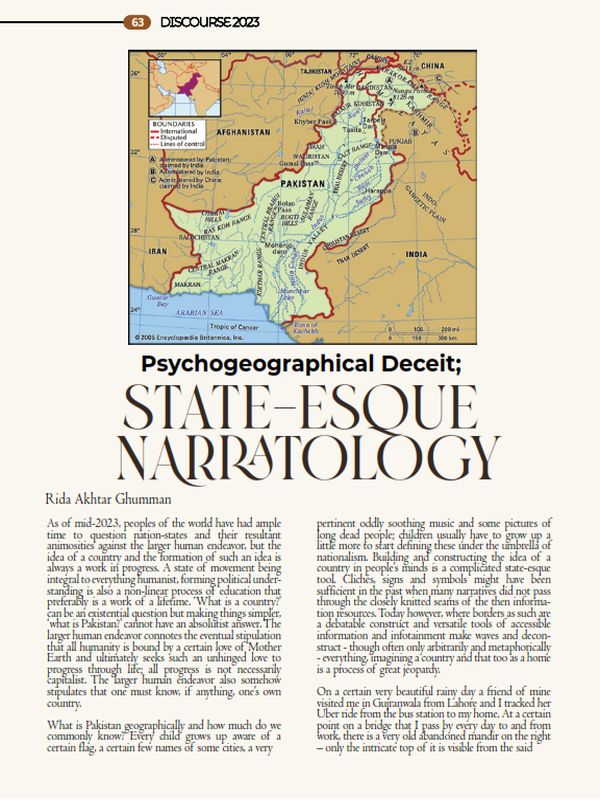

What is Pakistan geographically and how much do we commonly know? Every child grows up aware of a certain flag, a certain few names of some cities, a very pertinent oddly soothing music and some pictures of long dead people; children usually have to grow up a little more to start defining these under the umbrella of nationalism. Building and constructing the idea of a country in people’s minds is a complicated state-esque tool. Clichés, signs and symbols might have been sufficient in the past when many narratives did not pass through the closely knitted seams of the then information resources. Today however, where borders as such are a debatable construct and versatile tools of accessible information and infotainment make waves and deconstruct – though often arbitrarily and metaphorically only- every thing, imagining a country and that too as a home is a process of great jeopardy.

On a certain very beautiful rainy day a friend of mine visited me in Gujranwala from Lahore and I tracked her Uber ride from the bus station to my home. At a certain point on a bridge that I pass by every day to and from work, there is a very old abandoned mandir on the right – only the intricate top of it is visible from the said point while sadly below it is a tyre shop – and the samadhi of a great man from two centuries ago on the left which is ensconced by several amaltas trees that were in pure bloom when she was passing by. I asked her to try and catch glimpses of both though fully knowing that you cannot ascertain both simultaneously: there is way too much history in that certain point only and passing by is not enough.

The Pakistan Studies syllabus is integral to all educational programs in the country, from grade 01 to grade 14. This syllabus usually roughly starts around ideology, the Pakistan movement, the process of the formation of the constitution, some selected regimes and ends with some chapters about the geography and climate of Pakistan. Fourteen years of education with the same course is somehow the repetition of the same syllabus. Prof Dr. Eqbal Ahmad once wrote that “every policy that begins on the assumption of keeping someone weak forever is doomed to fail.” (Barsamian) It is not out of the box to say that teaching such a syllabus, for so long, devoid of any emotional consonance with the geography of one’s country is a weakening policy. Pakistan Studies syllabi, if anything, should talk about the colonial past of the sub-continent, the pre-colonial ages of unique communities and the post-colonial decadence of a region into several separate states. Learning this however shall help people understand these smaller states that haggle and hide histories by policy. Prof Dr. Ahmad also wrote, “I do not know of any country’s educational system that so explicitly subordinates knowledge to politics.” (Ahmad) History seeps every inch of Pakistan’s being. The state’s silence however about psychogeographical wisdom is a penchant for research. Aren’t the benefits of knowing way too obvious?

Psychogeography is a domain of knowledge that connotes ascribing psychological connection with a geographical setting. Knowing areas and vestibules of history around you is an empowerment par excellence. Where knowing as a state of delusion can do only enough good, knowing as a state of empowerment is a process of connecting with the larger human endeavor of manifesting love. Mehmood Qalandari, a local Seraiki poet of Wasaib, has a quatrain that loosely translates,

If education means to know the common alphabet

Then I don’t have an education,

But if education means to read the eye, the face, the motherland,

If education means to understand the shrubs and the leaves than I have a PhD.

Forming camaraderie with peoples around you – peoples because there are many groups of separate people in Pakistan – is an endeavor that asks for an education that goes beyond the alphabet of the state and delves into the alphabet of the land around. Such an education ensures a knowing that is one step ahead.

Forming a psychogeographical connection with a land is praxis of empowerment that could enable a reflective approach amongst any people. Having a reflective praxis with a syllabus that is induced with knowing the micro realities of a land, her history and her vastness could enable any people with the power of “moving away from the ideological trap that distinguishes theory from praxis.” (Bernd Reiter) Theoretically knowing the climate of Pakistan hasn’t necessarily been very fruitful for the landscape of the country, as definitions of climate are very vague now, whereas practically knowing and making such knowledge a praxis could perhaps enable a referential connection to that land that is necessary today more than ever. Finding allies in local trees, leaves and weathers could help one inundate with the banal realities of a land like finding ally ship with a local street cat helps manifest a mutualism and beauty in life that is raw and pure to the core; beauty and camaraderie when manifested raw are progress within the spectrum of a country; progress like this that is beyond capital helps instantiate ideas of a country that does not necessarily need to dwell in borders, markers and wires. A country that forms itself around narratives that are in lieu with the larger human endeavor is a country that shall perhaps not need songs, signs and symbols of dogma and deceit.

References

Ahmad, Eqbal. Between Past and Future: Selected Essays on South Asia. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004. Print.

Barsamian, David. Eqbal Ahmad: Confronting Empire. London: Pluto Press, 2000. Print.

Bernd Reiter. Constructing the Pluriverse: The Geopolitics of Knowledge. Durham: Duke University Press, 2018. Print.