Public Policy & Economic Growth in Pakistan (Blog)

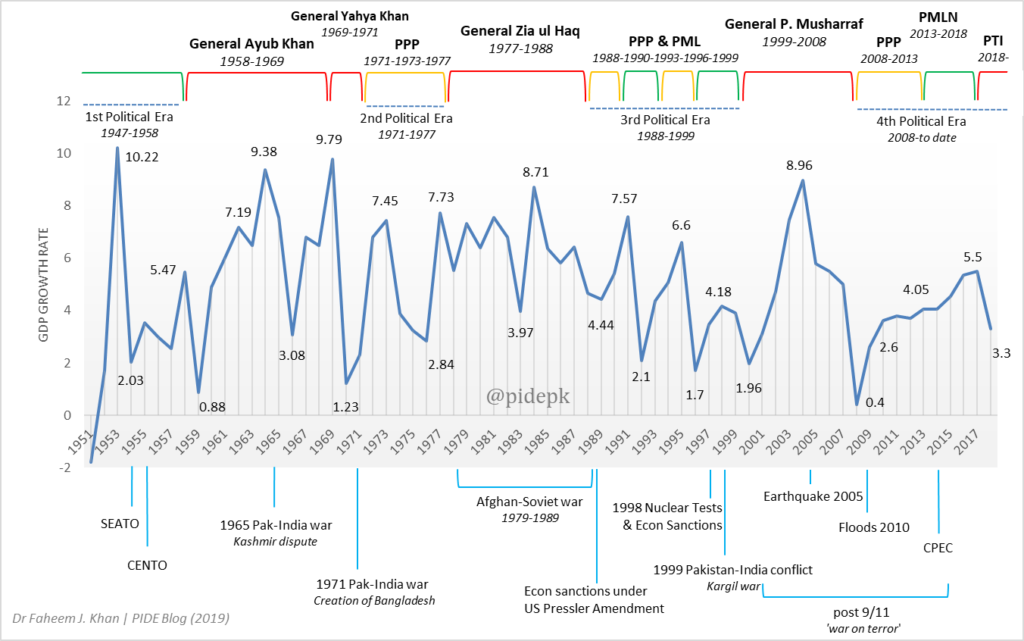

Pakistan’s history is characterised by political instability, multiple military coups (1958, 1969, 1977, 1999), conflict with neighbouring India over water resources and Kashmir (1965, 1971, 1999), the creation of Bangladesh from East Pakistan (1971), episodes of love and hate relations with the United States (1960s, 1980s, post 9/11), the state’s involvement in the Afghan-Soviet war (1979-1989), and its role as a frontline state in the ‘war on terror’ (2001 onwards). Furthermore, two massive natural disasters – a 7.9 magnitude earthquake in October 2005 and unprecedented floods in July-August 2010 – accompanied by internal security hazards, ethnic strife, energy crisis and global economic recession have undermined the continuation of development policies. Over the years, these events have resulted in unsteady economic growth, short-lived economic booms, and external and internal conflicts.

In her book on ‘The Struggle for Pakistan: A Muslim Homeland and Global Politics’, Ayesha Jalal (2014) explains how the vexed relationship with the United States of America, border disputes with neighbouring Afghanistan in the west, and unending conflict with India over Kashmir in the East, combined with ethnic rivalries have created a siege mentality that encourages military domination and militant extremism in Pakistan.

Over the last six decades, despite multiple collaborations with development partners and receiving huge amounts of foreign aid with considerable variations over time, Pakistan is still far from the stage of self-sustaining economic growth. Pakistan’s growth experience of the last four decades suggests volatile annual growth and declining trend in long run growth patterns. A regime analysis tells us that the average GDP growth rates were higher during the military governments as compared to the tenures when democratic governments were in power. However, higher inflows of foreign economic assistance, international trade support and debt relief have played an important role during military eras. A GDP growth comparison of regional economies, during 2009-2019, shows that Pakistan is a worst-performing economy. It grew on average 4.1 percent which is way behind the growth rates of Bangladesh, India and China.

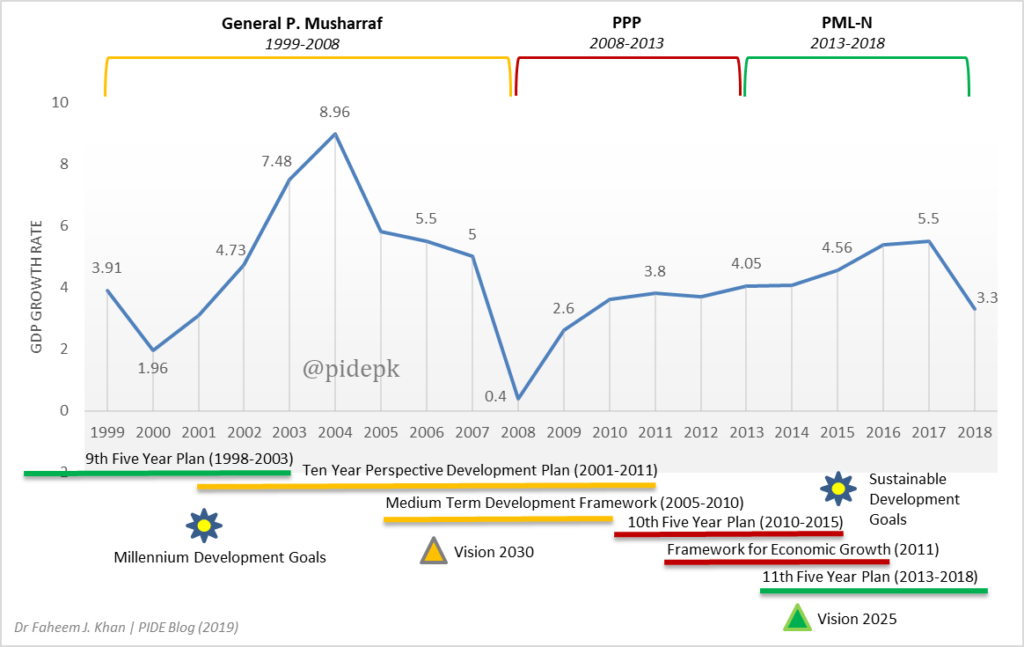

Over the years, political instability, inconsistency in public policy-making and lack of policy persuasion have played a detrimental part in undermining the state’s role to cope with the deteriorating socio-economic conditions in Pakistan. Figure belowshows proliferation of policies, their tenure and GDP growth trend during the last three regimes (1999-2018).

Pakistan entered the 21st century without a comprehensive action plan to improve the living standards of its people. During the last two decade, multiple medium to long-term national development plans were formulated, but only one of them – the MTDF 2005-2010 – has completed its planned policy period while all others were either discontinued or replaced by a new policy plan/framework. During the same period, international development agenda – the Millennium Development Goals (MDG) and Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) – heavily influenced the national and sub-national policies. All plans, except the Framework for Economic Growth (2011), were formulated keeping in view the MDG and SDG. Limited attention was given to the indigenous approach towards public policy. Perhaps that is why Pakistan failed to achieve most of the MDG targets and today following SDG targets with vague approach.

Almost all medium to long-term plans prepared during political and/or military regimes were shelved in the country’s history after change in leadership. Despite wide circulation of these plans, hardly anyone reads them, understands them, implement them! Hence, broadly speaking, none of them succeeded in getting the desired results. Over the years, national and sub-national development plans have become more of a formal presentation document than actual action plans. Priorities of projects and programs have replaced the formulation and implementation of policies in Pakistan. This can easily be seen through the Public Sector Development Program (PSDP)/ Annual Development Plans (ADP) documents; selected projects in selected policy areas get adequate allocation of funds for speedy completion on the cost of others equally important policy interventions.

Among others, visibility is an important factor that influence governments’ priorities. Here, visibility may refer to governments’ sensitivity to their appearance in the development process which could improve their reputation or profile to receive public appreciation. Research evidence indicates that politicians in Pakistan often initiate politically-driven projects and tag their name or party’s slogan on these project activities partly to enhance their political reputation and visibility. Evidence also suggests that in pursuit of political reputation, every new regime seeks to abandon active projects launched by previous governments and take certain development initiatives to differentiate themselves from their opponents and previous governments. In this process, the political leadership often opt for quick-fixes and initiate politically-driven projects partly to enhance their political reputation and to achieve short-term political gains. It was observed that politically-driven projects were often heavily funded, expensive, sometimes technically flawed, and had less impact partly due to political considerations that directed the objectives.

The presence of numerous development partners in Pakistan have also played a role in discouraging the governments to design and implement a more holistic localized development agenda by extending financial and technical assistance; undermining state capacity and creating addiction for ready-made solutions to complex domestic problems. Having said that, the government also lacks adequate resources and capacity to come up with comprehensive solutions to complex problems. There are acute shortages of specialists/technocrats in the government. Policy-makers do talk about the importance of evidence-based decision making, but the importance of research & development and data governance are often ignored. The quality and efficiency of civil bureaucracy – practitioners who are responsible to transform policy into action – has deteriorated over time. These have increased government’s reliance on outsiders such as consultants, advisors and contractors to do miracles in short period of time. Although these consultants, often paid by the development partners, are experienced in their specialised fields, they lack understanding about the dynamics of public policy processes in Pakistan.

It is interesting to note that public policy problems are well known to everyone. It is broadly known what’s wrong with the system; civil bureaucracy, institutions, education sector, health sector, water and sanitation etc. The problem at large is ‘how to reform?’ in such a way to improve the functioning of the government in general and public service delivery in particular. The answer would never be simple, but what hampers reforms in Pakistan is the ambition to bring massive reforms in the system both vertically and horizontally at one point of time after long breaks. This approach failed multiple times. The new approach should be to take smaller but incremental steps, more considerably and regularly. Reform should be participatory, transparent and continuous process at all levels. Finally, policy persuasion and collective action are inevitable to sustainable development. As of today, there is no formal platform in Pakistan where development partners, government organisations and other stakeholders could interact frequently, share information, float innovative development ideas, and learn best practices so that they can contribute to the development process more productively. In the absence of these formal specialized platforms, organisations with different perceptions about the problems and preferences for the solutions pursue their own (competing) objectives. Absence of formal platforms results in fragmentation of ideas, weak coordination between multiple organisations, duplication of initiatives etc. In such a scenario, it can empower a few influential organisations holding critical resources in the policy network. It is likely that the presence of a few influential organizations and strategy to influence public policy in one-to-one engagement explain the absence of formal platforms. Think tank like the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics (PIDE) can and should fill this gap by formulating specialized policy platforms for public policy research, debate and mutual learning.