Reforms – Monetary and Fiscal

I will only point to two areas, where, without fundamental reform in the principles for their management, our prospects for higher economic growth will remain bleak.

One is the shrinking domestic resource base available to finance growth. The second is the misapplication of the NFA, where the overarching system for raising taxes is unwieldy and tedious, beset with misalignment of incentives.

Domestic Resource Base

Pakistan has a severely constrained financial resource base. The country has managed to avoid financial paralysis through the liberal use of cash injections by the SBP, via Open Market Operations (OMOs) – in an amount now slightly more than total private sector credit to the private sector.

Two aspects of our financial profile are responsible for this state of affairs.

First, an outsize ratio of Cash in circulation – at 40% of deposits, is a multiple of that in other, including developing, countries. Hence, we have a national bank deposit base that again is similarly small as a percentage of GDP.

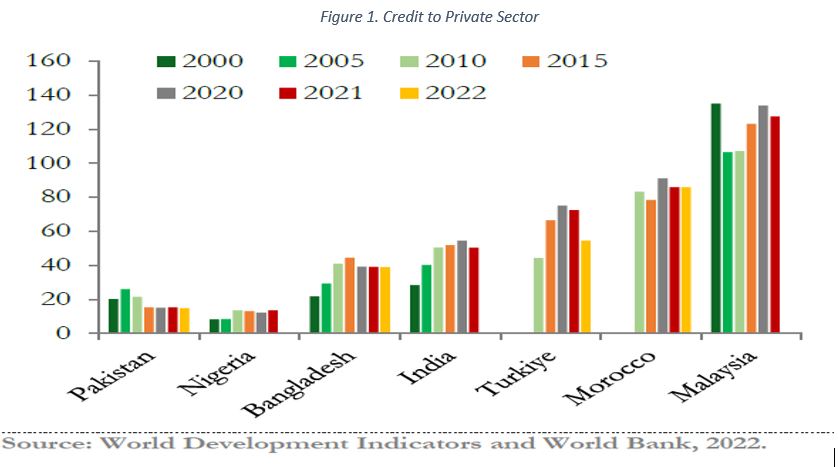

Second, the government’s near-complete reliance on banks for budgetary deficit financing, which has reduced the capacity of the system to finance the private sector, to about 25% of banks’ lending capacity – from 75% 15 years ago as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Credit to Private Sector

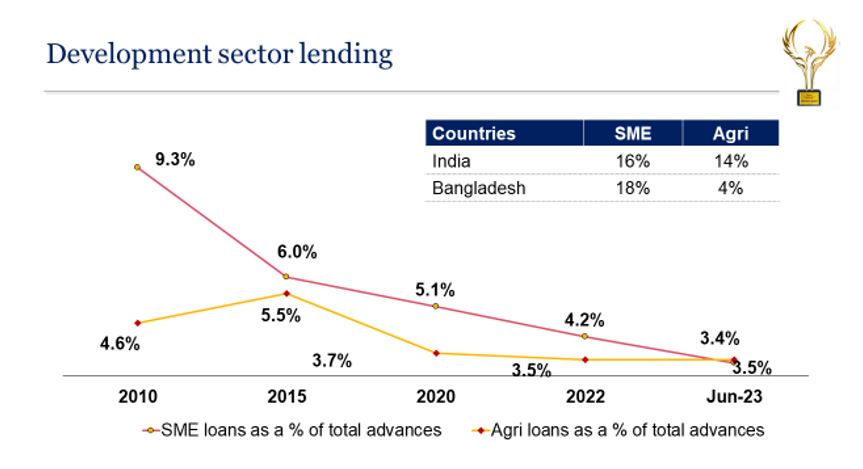

Unlike other developing countries, we lack entirely, dedicated development banks, that are usually public-sector managed. Since our commercial banks favour lending to the established corporate sector, the amount lent to the SME and agriculture sectors has declined to 7% of private sector loans as shown in Figure 2. This situation largely nullifies the role of the banking sector as an agent for development.

Figure 2. Development Sector Lending

There are several clearly identifiable and viable, steps that need to be taken to enlarge our financial resource base for development finance. I will only point out the headings involved, without elaboration.

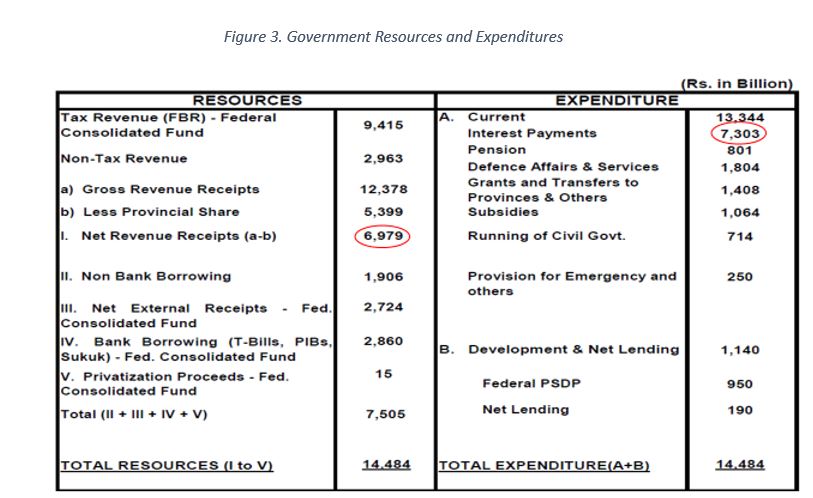

a) The Governments debt-management office (DMO) lacks principled objectives, market knowledge, professional skills, and is a passive, debt-stuffing function. Some 80% of government TBs and PIBs are held by banks, and only 20% of government debt is fixed rate, long-term debt. The immensity of the burden imposed in having 80% debt at floating rates is evident as the government has borne the overwhelming cost of the rise in SBPs policy rate, from 6.5% in 2016, to 22% in 2022 during FY 24. Government’s interest cost well exceeds net Federal Government revenue (Rs 7.3 trillion vs. Rs 6.9 trillion) as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Government Resources and Expenditures

The most fundamental reform needed is the creation of a professionally managed DMO. Borrowing has to broadened out of the banks to use the Stock Exchange as a channel for debt subscription; to the much greater use of Mutual and Money Market funds; use of Roshan to draw NRP investment; more Sukuuk issues to draw Islamic investors, etc.

b) Reduction of cash in circulation must be undertaken on a crisis footing. 100% digitisation of all government payments and receipts is necessary. The RAAST network involving direct interoperability between bank accounts will seamlessly facilitate receipts and transfers. Digitisation of all property records and all future transactions is also necessary, as property business is conducted with a large share of cash, to match understated property values. Crackdown and exemplary penalties for commodity hoarding will also reduce cash volumes. As some 90% of all retail payments in Pakistan are in cash, the enforcement of QR codes at all sizes of the 2 million plus retail outlets will significantly assist in reducing cash held for transaction needs. The transfer of cash to bank deposits, will, through the banking multiplier, lead to proportionately much higher (3x) growth in bank deposits.

c) Once the DMO function is professionalised, the government must issue LT debt in 5 and 7 year maturities, to enable the establishment of risk-free, liquid, sovereign debt peg points, that will then allow the corporate sector to move some of its debt out of banks, to the broad investor market, via the issue of fixed rate corporate bonds – not possible today, given the absence per-points.

There are a number of other peripheral matters related to the calculated suppression of cash domination.

Collection Responsibilities and the Rectification of Federal-Provincial Tax Imposition

The current superstructure leads to misalignment of incentives for both the Federal and Provincial Governments, and is an impediment to efficiency and effectiveness of individual aspects of the national tax policy. There is a broad frame to address here, but in crude summary:

a) Due to inadequate regularisation of the devolution structure, the Federal Government bears responsibility for 66% of national taxes while it retains only around 40% of national tax revenues. This undermines the incentive for the federal government to raise taxes that are subject to the NFC sharing formula: to raise Rs. 100, the federal government will have to raise taxes by Rs. 235, building a bias to raise more non-divisible cash revenue. Similarly, the Provincial Governments raise only 8% of national taxation. They are well-funded by federal transfers, and so greatly under-apply their own powers to raise taxes on agricultural income and property. Clearly, the Federal Government must make full transfer of all the expenses of the devolved departments, as well as the expenses it picks up on semi-autonomous bodies, such as the HEC and schemes like BISP. While this must be part of a broader discussion, it is suggested that it may be worth clubbing agricultural income tax with the monopoly of the Federal Government on income tax in general. Similarly, property taxes could be devolved to the Local Government tier, best suited and able to gauge, set and collect property taxes.

b) Overall, there are 70 different taxes in Pakistan, administered by 37 different entities with frequently unlinked data bases and multiple tax rates: 26 for goods and even more for services. Tax consolidation is long overdue; databases must be integrated, else both collection and performance evaluation will be complicated.

The author is a former Governor of the State Bank of Pakistan.