Social Protection in Pakistan: Reforms for Inclusive Equity

Over one-fourth of our population appears to be poor today in the sense that they are unable to fulfill their basic needs. Although absolute poverty has declined overtime, the number of poor today exceed what the country’s population was in 1947. A continuation of efforts made in the past to alleviate poverty in Pakistan is represented by the currently widely publicised social safety nets.

Over time, the country opted for a number of poverty alleviation and social protection measures, i.e., Village Aid and Rural Works Program in the ‘50s and ‘60s, Zakat in the ‘80s, Bait-ul-Mal in the ‘90s, poverty reduction strategy paper (PRSP) in the early 2000s, the emergence of Benazir Income Support Programme (BISP) in 2008 and formulation of a dedicated ministry on poverty alleviation in 2019 at the federal level. After the 18th Constitutional Amendment, the provinces also took a number of social protection initiatives in their jurisdiction. For example, Punjab established a social protection authority to oversee social protection initiatives.

The country has witnessed massive public spending on social protection and poverty alleviation initiatives in the last two decades. It currently stands at more than a trillion rupees compared to PKR 500 billion in 2015. Alone the BISP allocation went up tremendously; it was PKR 34 billion in 2008, PKR 102 billion in 2015 and PKR 460 billion in the ongoing year. The origin of recently coined social safety nets can be linked to sluggish economic growth, high inflation and especially donor-sponsored motives. Broadly, the ongoing social protection programs have three categories:

- In social insurance programs, beneficiaries pay a certain fee over a while to be eligible for benefits later. Four main operational programs are Employees’ Old-Age Benefits Institution (EOBI), Worker Welfare Fund (WWF), employee social security institutions (ESSIs) and government employee pension schemes. Except for government employee pensions, the rest of the programs target a limited number of beneficiaries primarily due to the need for more knowledge, the informal economy, and the outdated design of schemes.

- Social assistance programs are non-contributory interventions for the poor and marginal segments. Examples are Zakat, Pakistan Bait-ul-Maal (PBM), Benazir Income Support Programme (BISP), Sehat Sahulat Health Insurance, Punjab Social Protection Authority (PSPA), Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Health Card, and social welfare initiatives by provinces. Some of them have experienced massive budget expansion.

- Labour market programs aim to build and develop skills among the youth and protect them from unemployment. They could be contributory or non-contributory. Federal and provincial vocational and technical training bodies manage several schemes, e.g. Prime Minister’s Youth Skills Development Program. This is besides the various microfinance schemes aimed to alleviate poverty, i.e., Rural Support Programmes Network (RSPNs), Microfinance Networks, etc.

A wide range of individual, community and corporate philanthropic activities are also operational in Pakistan. Around 98% of Pakistani society shows charitable behaviour. The volume of individual giving stood at PKR 240 billion in 2016 (estimated by the Pakistan Centre for Philanthropy). The corporate philanthropy is more than PKR 8 billion. These numbers are largely under-reported due to lack of clear regulatory frameworks. One may see the annual budget of Edhi Foundation and many other philanthropic organisations. For example, the annual donations of Indus Hospital in 2022 were more than PKR 50 billion.

Are they Helpful in Building Inclusiveness?

The question arises, are these initiatives are helpful in building resilience, equity and opportunity among the vulnerable segments of the population? The answer, unfortunately, is no…

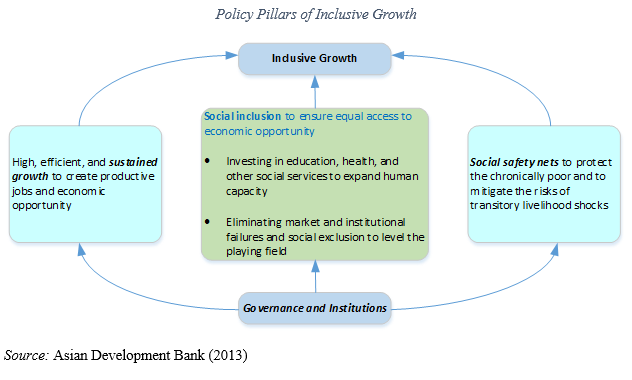

First, they are largely politicised and donor-driven. Alone, social protection programs cannot alleviate poverty without sustained economic growth and social inclusion. It is the economic growth that is supposed to create jobs and opportunities along with investment in human capital and overcoming market barriers and institutional failures. Expecting social protection as a ‘magic bullet’ for poverty alleviation is a false paradigm in the absence of sustained economic growth and skill development.

Second, many of the social protection initiatives need an innovative targeting approach. They were designed a few decades ago and now seem to be a public burden, i.e., PBM, Zakat, WWF, EOBI, etc. A significant part of the budget goes into financing just their administrative expenses. Only donor-sponsored programs are able to rapidly expand.

Third, many initiatives are too ambitious, e.g. universal health insurance scheme. None of the countries in the world offer such facilitation to their citizens. Pakistan currently lags behind most of its neigbours in terms of key economic indicators and its income is almost the same as many developed countries enjoyed 80-100 years ago; however, most donors-driven initiatives are pushing us towards whatever social protections schemes are currently in place within the USA, Germany, etc.

Fourth, social protection is mainly a provincial subject after the 18th Constitutional Amendment. Almost all the provinces lawfully owned the responsibility by designing and initiating various schemes. It is still incomprehensible why the federal government established a dedicated ministry on poverty alleviation is constantly expanding social protection initiatives. This has led to a lot of duplications where a beneficiary is benefiting from multiple similar schemes.

Fifth, there is no comprehensive social protection framework acceptable to various government tiers. The country has spent trillions over the past two decades without any policy guidelines. Resultantly, these initiatives largely failed to endorse equity and resilience by promoting better economic opportunities among marginalised segments. Today poverty is almost the same and there is a dearth of information on how much the various sorts of poverty alleviation schemes have helped recipients graduate out of poverty. No concrete study is available to evaluate National Rural Support Program (NRSP), RSPNs and Microfinance Networks.

Reforms in Social Protection

Following policy reforms would be help synergise the social protection and poverty alleviation initiatives in the country:

- There is a need to realise that economic opportunity for the poor largely depends on economic growth and social inclusion rather than handouts. We need sustained economic growth to absorb the youth bulge and investment in skills development to promote entrepreneurship and decent jobs. Policymakers must realise that social safety nets cannot be a substitute for opportunity. A stable macroeconomic environment is the

prerequisite for job creation and pushing the people out of poverty. - We need a clear social protection framework. This can only be done by clearly enlisting the responsibilities of various government tiers. A policy shift is required in the program’s design where all organisations act together in a coordinated manner to avoid duplication and graduate the people out of poverty. We must review the graduation design of various microfinance programs.

- A strategic shift is required from unconditional cash transfers to conditional transfers to improve education and health outcomes. Market-based skills must be introduced to the youth, especially for women, to improve their quality of employment. Such interventions may be accompanied by microfinance loans.

- The private sector owns the most extensive philanthropic activities. To effectively pool resources, specific mandates may be handed over to the private sector, e.g., public-sector ambulances along with financial resources may be handed over to the Edhi foundation to administer effectively. A successful example is the handover of various public hospitals to Indus Hospital and Health Network.

- Let’s replace ‘social protection initiatives’ with ‘economic security programs’. Hence, reforms must focus on minimising inefficiencies, distortions and politicisation of schemes. There is a need to promote equity, both inter-generational and between income groups. All this requires improving individual capabilities to command resources and provide marginalised groups with economic opportunities to be resilient and have an aspiration to change their life in an autonomous manner.

The author is the Chief of Research at the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics (PIDE), Islamabad.