The Islamabad Master Plan

The Islamabad Master Plan

Islamabad is currently in the process of reviewing its master plan. Like most cities in the developing world, Islamabad is facing insufficient public utilities, lack of affordable housing, commercial and office space, decaying public infrastructure, illegal and haphazard development and mushrooming slums. What was planned to be ‘a city of the future’ by its architect C. A. Doxiadis and named ‘Islamabad—the Beautiful’ by its residents is turning into another case of urban decay (See also PIDE Policy Viewpoints 2, 12 and 13 and Haque and Nayab 2020).

-

THE CONTEXT

In 2017, the Supreme Court of Pakistan took suo motu notice of irregular development in Islamabad and directed the government to find a solution for regularizing these constructions. Later, Islamabad High Court in its judgment dated 9th July 2018 directed the government to form a commission to review the Islamabad Master Plan. Consequently, a commission was formed in August 2019 to review the master plan and give its recommendations.[1] The question arises, would another master plan revive Islamabad? We contextualize this discussion by delving into the history of the city.

-

ISLAMABAD—THE CAPITAL

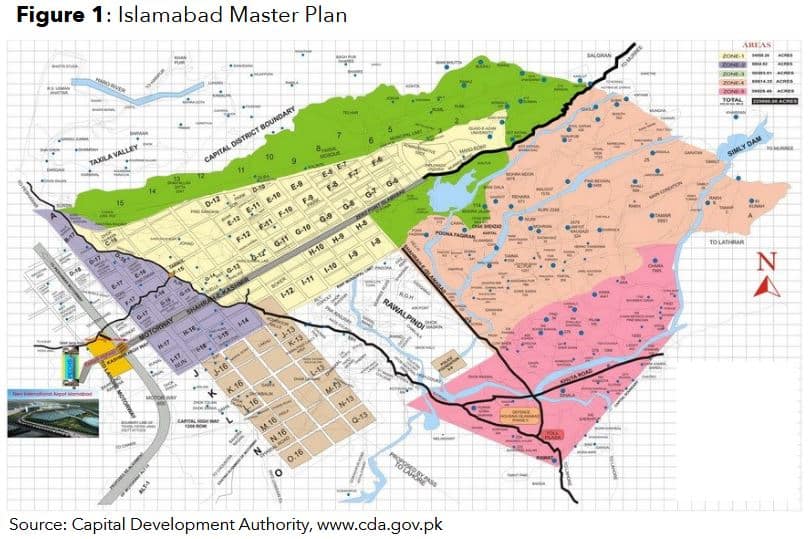

Islamabad was made capital of Pakistan in 1960. It was conceptualized as a symbol of unity in an ethnically and geographically divided country, flag bearer of modernity, and the seat of the central government[2]. Through Capital Development Authority (CDA) Ordinance 1960, CDA was created and entrusted with the authority to manage and develop the city under MLR 82. In 1992, the CDA promulgated the Zoning Regulation 1992 and divided Islamabad into five zones. In Zone 1, only CDA could acquire land for development. In Zones 2 and 5, private housing societies could take up development activities. Zone 3 was reserved area. Zone 4 was kept for multiple activities including National Park, agro-farming, educational institutions and research and development.[3]

Islamabad was planned as a low-density administrative city. Curiously, a Greek architect C. A. Doxiadis, was hired for the purpose. He operated as a development consultant more than an architect.

Constantinos Apostolou Doxiadis (1913-1975)

C. A Doxiadis was a Greek architect/town planner and the lead architect of Islamabad, the new capital of Pakistan. In 1951, he founded the private consultancy firm – Doxiadis Associates – and undertook projects in many developing countries of the world. “A crucial element in Doxiadis’s modus operandi was his attempt to shore up business success through the excessive branding and mystification of his personality and work. His theoretical discourse abounded in neologisms and unique technical terms – ‘Ekistics’, ‘ecumenopolis’, ‘machine’, ‘shell’, ‘dynapolis’, etc. – which were meant to lend an air of distinctiveness to proposals that often shared more with prevailing architectural fashions than he was ready to admit” (Daechsel 2015). But from all of the projects, he considered Islamabad as his best town planning. Islamabad plan was conceived in 1959 and it took 4 years to complete the plan.

2.1. The Grid Iron Pattern of the City

Doxiadis planned Islamabad on a grid-iron pattern. The fundamental grid of 2000 x 2000 meters divides the city into 84 sectors, the other is the ‘natural’ grid created by ravines flowing through the entire site area.

Each sector has five sub-sectors – four residential and one commercial (Markaz), which is encircled by auto routes with pedestrian networks within the sector[4]. Each of the sector would be low slung and basically comprised of single-family homes on an American

____________________

[1]This, by no means, is the first attempt at reviewing the master plan. Previously, two commissions were formed without much success in getting approval of the government. The first commission worked from 1986-92, and the second from 2005-08.

[2] Some argue the move was meant to consolidate power, away from the commercial interest of the business community in Karachi – the first capital of Pakistan.

[3] Initially, the Metropolitan Islamabad was divided in three parts: Islamabad; National Park and Rawalpindi. In 1979, Rawalpindi separated away from the Metropolitan.

[4] All sectors were to have a mix of low-income, middle-income and upper-middle-income houses.

suburban model. There was no zoning for the poor. Neither did he plan for a city center – a Commercial Business District (CBD). The only job market he planned for was the government with its secretariat at one end of town. Even the University was out of town and hence cut off from the city housing and labor market.

His concept was quite strange, requiring people to remain confined to their sectors seldom feeling the need to go beyond. Within the sector, they could walk to neighborhood shops and schools. He also did not plan for extension thinking that the originals setting was enough, and that the capital would demand nothing more than the government.

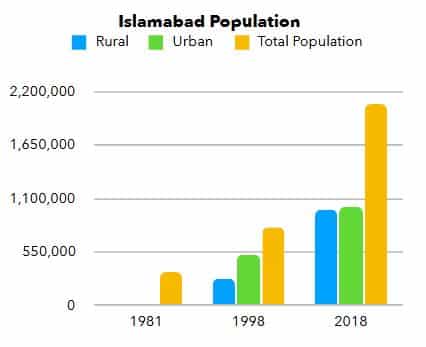

CDA and the courts have tried to remain true to the Doxiadis’ conceptualization, perhaps because they benefit from the expensive suburban setting in the hills. Yet in-migration has happened far faster than envisaged and Islamabad now has more than 2 million inhabitants. Doxiadis’ plan has been stretched and tweaked but continues to suffer from its birth defects: no CBD, room for the poor and elongated car dependence.

Oddly enough, a CBD (more popularly known as the Blue Area) was attached to the masterplan to have 8-12 story linearly placed mixed-use buildings. However, this idea could not be materialized due to “lack of design expertise of the CDA. To disguise the incompetence, the CDA officials argued that residences on both sides of the commercial area would have their view of the Margalla Hills destroyed” (Mahsud 2013, italics added). Besides it is difficult to think of a functional CBD with a highway passing through it and requiring a car to move around.

-

DOXIADIS’ MESS—ISLAMABAD AND ITS PRESENT CONUNDRUMS

The Islamabad Master Plan, being no exception to master plans elsewhere, has resulted in contrived urban development and stifling of economic activities. The land and building regulations are too rigid and have resulted in over-regulating Islamabad, limiting both social and economic potential of the city.

3.1. Horizontal vs Vertical Development: The case for Densification against Sprawl

Islamabad has experienced significant urban sprawl owing to unrestricted growth in housing schemes and roads over large expanse of land, with little concern for urban planning.

- At present, the total population of Islamabad is 2 million.

- Housing backlog is about 100,000 units.

- This gap is expected to increase by 25,000 units per year.

- Currently, the supply is about 3000 houses annually.

- The CDA has not launched any new residential sector in the past twenty years. The last sector was launched in 1989 which has not seen any development since then (GoP, 2019).

Urban Sprawl has its own disadvantages and costs, in terms of increased travel time, transport costs, pollution, destruction of the countryside and arable lands. Reasons for this sprawl are obvious lack of adequate housing, office space, and commerce facilities in the city center.

The ordinary citizen does not have any say in the decision-making and planning of their own cities. This raises the pertinent question, are cities made for people or vice versa? Why living in a Pakistani metropolitan is so expensive?

3.2. Restrictive Zoning Laws- a Barrier to Sustainable Urban Development

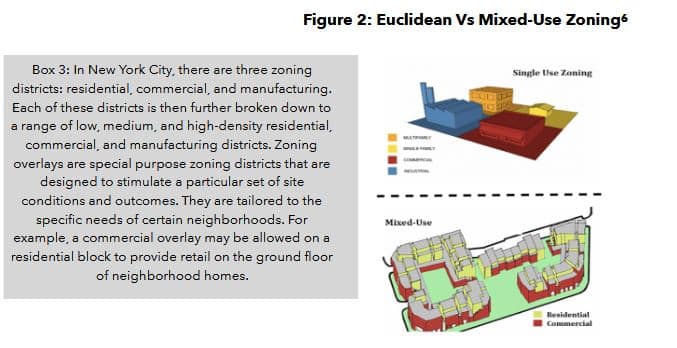

Part of the problem lies in restrictive zoning[5] in Islamabad that encourages sprawl and single-family homes against high-density mixed-use city centers and residential areas – more in line with the Euclidean zoning which favors single-family residential as the most preferable land use. This leads to inefficient use of land which is a premium asset for any city. Urban regeneration is possible by allowing some flexibility in zoning regulations. The Interim Report on Islamabad Master Plan proposes regeneration of sector G-6 through changes in zoning laws. Incorporating more sectors in this urban renewal will unleash innumerable possibilities for urban development.

-

RECOMMENDATIONS OF THE FEDERAL COMMISSION FOR REVIEW OF ISLAMABAD MASTER PLAN (2019)

The commission was tasked to comprehensively review the Islamabad Master Plan and submit its report.

(1) Amendments in building bylaws to encourage high-rise buildings in Blue Area, Mauve Area, Class III shopping centers and I&T center.

(2) Vertical development in zone 2 and 5 to restrict sprawl.

A Federal Commission was formed on third August 2019 for the comprehensive review of the IMP and submit its report accordingly. Given the paucity of time and resources, the commission put forth an interim report that outlined issues faced by the city, gave broad outlines to deal with these issues, and a suggestion to engage consultants for future studies. In short, after about sixty years since the first plan was made for Islamabad, the city is awaiting a plan that will solve its current problems.

___________________

[5] Zoning is a planning control tool for regulating the built environment and creating functional real estate markets. It does so by dividing land into sections, permitting land uses on specific sites. It determines the location, size, and use of buildings and decides the density of city blocks (City of New York 2015). Islamabad had its first zoning regulation in 1992 after the plan recommended by the first commission were not approved. Another amendment in zoning laws came when sub-zoning of Zone IV was approved in 2010.

[6] http://cnucalifornia.org/straight-line-radius-v-shortest-path-analysis-finding-right-tool-zoning-code/

(3) A ring road around Islamabad for better connectivity with other cities.

(4) Widening of existing roads to cater to ever increasing traffic flow.

(5) Mechanism for regularization of illegal and unapproved housing schemes.

(6) Municipal tax to be collected from residents and businesses for rehabilitation of roads, sewerage line, waste collection and disposal, water supply, rainwater harvesting, and other public utilities and amenities.

(7) Construction of three more mass transit lines to improve connectivity of Markaz with regional markets.

(8) Conversion of designated parking lots in Blue Area into multi story parking areas on BPT/PPP basis.

(9) Regeneration of G6 sector.

The ghost of Doxiadis and our own flawed urban thinking continues unabated. The recommendations of the commission continue to look after cars, and to restrict the development of high-rise while hanging on the suburban model. They appear to be oblivious to the needs of the homeless and the needs of the growing metropolis of 2 million people.

Shortage of Needed City Space

The planning paradigm of Pakistani cities is:

- Low rise (4-floor commercial areas) along wide roads

- Single-family houses and

- A priority to cars: very-widening roads with flyovers and high-speed lanes.

The result has been that the Single-Family home has become the unit for the economic activity taking on all activities such as:

- Schools

- Offices

- Leisure space

- Restaurants

- Shops

- Warehouses

Hence, it can be concluded that masterplans for cities within Pakistan have failed to recognize the variety of human needs or the growing population in cities. Instead, the preferred approach has been to force people into tight fantasies of planning divorced from emerging needs, technologies, or changing lifestyles. The result is that neighborhoods and needs wage a constant battle against the poor planning standards that are set up.

Courts have jumped into the game without any idea of what the sociology or economy of a city is. A developing country like Pakistan is, therefore, wasting real resources with businesses and livelihoods being destroyed and transaction costs inordinately rising as courts and planners try to enforce unrealistic and fantastic standards. This thoughtless planning is detrimental to economic growth.

-

MASTER PLANS ARE A RELIC FROM THE PAST

All our cities spend resources and time developing masterplans to lock themselves and their cities into a predetermined path of growth and lifestyles. When life does not adjust to these preordained plans for their life, cities and their residents end up in years of strife with encroachments happening involving lawsuits and law enforcement. Cities try to grow and modernize but planners go to the extent of destroying buildings with court injunctions only because they are a couple of feet taller or longer than allowed by stringent regulations.

Yet the push for master-planning continues across Pakistan hoping to keep cities frozen for long periods of time from 15-30 years.

Having seen a boom after the second world war, master plans are increasingly seen as a thing of the past. Reasons for this disillusionment are many:

- Master plans are forward-looking, laying the building foundations of a city for the coming twenty years. However, they rely on the present as well as past data to project future demand for infrastructure and public utilities. Little do the planners realize that these projections are often faulty.

- In Pakistan, master-planning seems to be an inside job between planners and builders who know them. Public participation in the planning process is often perfunctory or nonexistent. These plans, therefore, are never owned by the community nor do planners recognize the needs of the people.

- Master plans are often based on unrealistic assumptions about proposed economic potential of the area as well as the requirements of the population.

- Master plans are static in nature, made at one point in time by select few which makes them irrelevant fast and it’s the city dwellers who end up having to face all the ills of that planning.

- There is little flexibility built in to evolve the plan and move the city forward. They are often not updated on time, leaving room for vested interests to intervene and change rules in their favor.

- Master plans seem to dictate how markets should develop leaving no room for them to find their own level. It is thanks to master planning that we see shortage in several areas in our cities.

Cities are Markets

As Haque (2015, 2017) and Framework of Economic Growth argue cities are markets that facilitate economic growth, they must be allowed to grow. Markets create order, which manifests itself in the form of cities, based on price signals. When government intervenes to distort these signals through regulation, that order is also distorted (Bertaud 2018). Jacobs (1969, 1984) Florida (2012) and Glasser (2011) among others have suggested that cities have multiple needs for them to achieve their central role of driving innovation and creativity. As cities adopt to changing socioeconomics, technology, innovation and talent, none of these are foreseeable to the makers of long-term masterplans. Cities that drive productivity and growth are neither neatly planned nor laid out for suburban living and cars. It is the seeming chaotic nature of these cities that drives their productivity and growth.

For this reason, many cities are moving away from master plans to guidelines and rules that allow the needs of the market and investors to determine what should be built. The city planner only worries about social and community needs, public health and safety and other common issues but not with regulating everything in the city. Directed by needs, investors build flats, shopping malls warehouses, entertainment facilities etc. Plans then worry about the working of the city i.e., guidelines for safety and mobility, infrastructure and social, community and public space. A single mind (of a planner) cannot comprehend the complexities of social interactions among thousands of people.

Developing City Wealth

PIDE Policy Viewpoint 13 and Haque (2020) have pointed to how a modern city finances itself through proactive value creation which benefits citizens’ real estate wealth. If city administration adopts this approach rather than rigid master-planning and allows value creation for the benefit of cities, welfare will increase.

Cities often sit on a gold mine of assets that include not just real estate and public utilities but can also create wealth through socioeconomic uplift of its people and regeneration of decaying urban areas. These assets can be materialized through better city management (Detter and Fölster 2017). Singapore, for example, has built its economic and human capital through this approach (ibid). When this approach is adopted, cities seek to regenerate their neighborhoods in line with market needs. Such regeneration plans are in vogue these days and require market friendly thoughtful city planning.

Summing-Up

- The World has moved on from restrictive master planning. Master plans are time and data intensive. They rely on present data to make future projections which are often faulty. Being Static and mostly non-inclusive, they become irrelevant fast and leave ample room for maneuvering by vested interests. Their stringent requirements leave little space for markets to develop.

- Islamabad Master Plan (IMP) was a flawed exercise from the very start and failing to revise it every 20 years has increased the damage IMP is doing for the inhabitants of Islamabad.

- Newer methods like neighbourhood planning is used across the world and we should also employ them. Many new tools are developed which were not developed when IMP was made. Every year, the population of Islamabad is growing, although it was thought that people will come to Islamabad, serve the government, and then leave the city and new government servants will take their positions. It is clearly not happening as the population has risen to two With current rate of development, it would be impossible to sustain Islamabad as a city.

- Islamabad is an over-regulated city. City zoning has been very restrictive, favoring single-family houses with little scope for commercial and civic activities. Successful cities have regulations and zoning codes that are flexible to adjust to changing physical requirement of a city.

- Islamabad is not an affordable city for low-income groups to reside in. Real estate prices go up where height restrictions are excessive and building process is discouraging of construction. Rezoning helps development and increase of supply land to keep prices in check.

- As IMP is in the process of being re-evaluated, we suggest a complete paradigm shift in our approach to city management – a shift that should be applied to other cities in Pakistan.

New Paradigm for City Management

- Policy, research and thinking needs to move away from a spaceless approach to development by integrating the role of cities as engines of growth.

- Fiscal federalism needs to be urgently adopted for city growth and to allow cities adequate ownership of their land and resources.

- The zoning paradigm needs to move away from its current emphasis on upper class housing to one that recognizes the diversity of the functions of a city. It must favor density, high rise mixed use and walkability especially in downtown areas. In addition, it must favor public and community space while allowing for commerce, culture and education and other needed city activities. Zoning needs to be based on clear transparent processes based on open citizen consultations[7].

- Building regulations must be loosened to allow complex high-rise construction.

- City centres need to be developed for dense mixed use. Government ownership of city-centre land needs to be reduced if it is retarding downtown development. Commerce is to be given priority in city centres.

- City management should be professional, consultative and accountable. Cities must be able to hire out of their budgets without federal hiring restrictions such as the Unified/National Pay Scales and mandatory positions for the federal civil service. Moreover, decision-making must be based on open consultative processes.

________________________

[7] See also Hasan (1997) for this point.

REFERENCES

Bertaud, A. (2018). Order Without Design—How Markets Shape Cities. Cambridge, MA.: The MIT Press.

Daechsel, M. (2015). Islamabad and the Politics of International Development in Pakistan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Cambridge.

Dag, D. and S. Fölster (2017). The Public Wealth of Cities. How to Unlock Hidden Assets to Boost Growth and Prosperity. Washington: Brookings Institutions Press. Washington.

Florida, R. (2012) The Rise of the Creative Class Revisited. New York: Basic Books. New York

Glaeser, E. L. (2011). Urban Public Finance. Harvard University.

Haque, N. u U. (2015) Flawed Urban Development Policies in Pakistan. Pakistan Institute of Development Economics., Islamabad. (PIDE Working Paper 119)..

Haque, N. u U. (2017) Looking Back: How Pakistan Became an Asian Tiger by 2050. Karachi: Kitab (Pvt) Limited. Karachi

Haque, N. u U. (2020). Increasing Revenue for Metropolitan Corporation Islamabad. Pakistan Institute of Development Economics,. Islamabad. (PIDE Working Paper 173)..

Haque, N. uU., & and D. Nayab, D. (2020). Cities-Engines of Growth. Islamabad: Pakistan Institute of Development Economics. Islamabad

Haque, N. uU. & and PC Team. (2020). Framework for Economic Growth. Islamabad: Pakistan Institute of Development Economics. Islamabad

Jacobs, J. (1969). The Economy of Cities. New York: Vintage. New York

Jacobs, J. (1984). Cities and the Wealth of Nations. New York: Vintage. New York

Mahsud, A. Z. K. (2013) “Dynapolis and the Cultural Aftershocks: The Development in the Making of Islamabad and the Reality Today”, . In K. W. Bajwa, K. W. (ed.) Urban Pakistan – —Frames for Imaging and Reading Urbanism. Karachi: Oxford University Press. Karachi.

Pakistan, Government of (2019) Interim Report on Review of Master Plan of Islamabad (2020-2040). Prepared by Federal Commission in Collaboration with the Capital Development Authority. The Gazette of Pakistan. Islamabad. Avialable at: http://www.cda.gov.pk/about_ islamabad/mpi/reports

PIDE Policy Viewpoint 12 (2020) Lahore’s Urban Dilemma- Doing Cities Better. Pakistan Institute of Development Economics., Islamabad.

PIDE Policy Viewpoint 13 (2020) Strategies to Improve Revenue Generation for Islamabad Metropolitan Corporation. Pakistan Institute of Development Economics,. Islamabad.

PIDE Policy Viewpoint 2 (2007) Renew Cities to be Engines of Growth. Pakistan Institute of Development Economics., Islamabad.