The Song Remains the Same

‘Environmentalism without class struggle is just gardening’.

-Chico Mendes

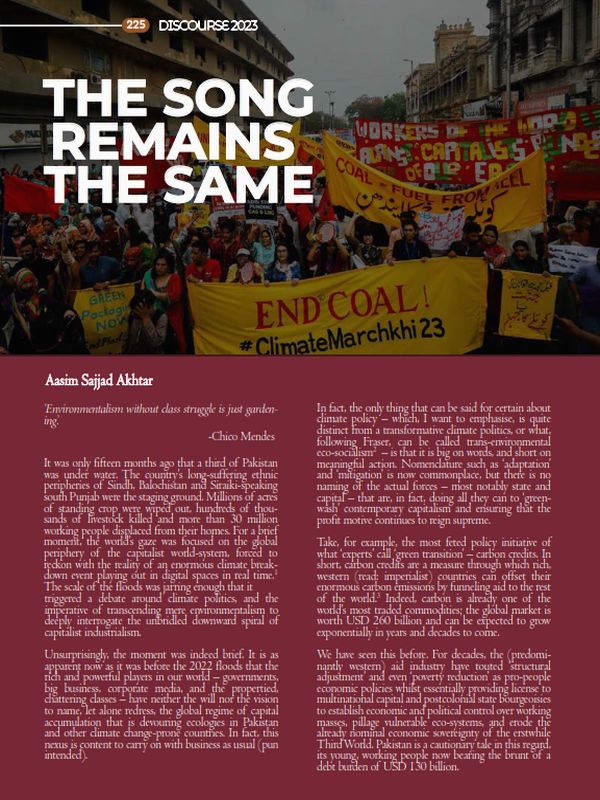

It was only fifteen months ago that a third of Pakistan was under water. The country’s long-suffering ethnic peripheries of Sindh, Balochistan and Siraiki-speaking south Punjab were the staging ground. Millions of acres of standing crop were wiped out, hundreds of thousands of livestock killed and more than 30 million working people displaced from their homes. For a brief moment, the world’s gaze was focused on the global periphery of the capitalist world-system, forced to reckon with the reality of an enormous climate breakdown event playing out in digital spaces in real time.[1] The scale of the floods was jarring enough that it triggered a debate around climate politics, and the imperative of transcending mere environmentalism to deeply interrogate the unbridled downward spiral of capitalist industrialism.

Unsurprisingly, the moment was indeed brief. It is as apparent now as it was before the 2022 floods that the rich and powerful players in our world – governments, big business, corporate media, and the propertied, chattering classes – have neither the will nor the vision to name, let alone redress, the global regime of capital accumulation that is devouring ecologies in Pakistan and other climate change-prone countries. In fact, this nexus is content to carry on with business as usual (pun intended).

In fact, the only thing that can be said for certain about climate policy – which, I want to emphasise, is quite distinct from a transformative climate politics, or what, following Fraser, can be called trans-environmental eco-socialism[2] – is that it is big on words, and short on meaningful action. Nomenclature such as ‘adaptation’ and ‘mitigation’ is now commonplace, but there is no naming of the actual forces – most notably state and capital – that are, in fact, doing all they can to ‘greenwash’ contemporary capitalism and ensuring that the profit motive continues to reign supreme.

Take, for example, the most feted policy initiative of what ‘experts’ call ‘green transition’ – carbon credits. In short, carbon credits are a measure through which rich, western (read: imperialist) countries can offset their enormous carbon emissions by funneling aid to the rest of the world.[3] Indeed, carbon is already one of the world’s most traded commodities; the global market is worth USD 260 billion and can be expected to grow exponentially in years and decades to come.

We have seen this before. For decades, the (predominantly western) aid industry have touted ‘structural adjustment’ and even ‘poverty reduction’ as pro-people economic policies whilst essentially providing license to multinational capital and postcolonial state bourgeoisies to establish economic and political control over working masses, pillage vulnerable eco-systems, and erode the already nominal economic sovereignty of the erstwhile Third World. Pakistan is a cautionary tale in this regard, its young, working people now bearing the brunt of a debt burden of USD 130 billion.

Many otherwise reasonable commentators often argue that creditors like the IMF and World Bank never imposed such neoliberal policies on Pakistan, and our own rulers are primarily responsible for the cumulative mess that present and future generations of working people have inherited. But this is a naïve reading of how political and economic power operate on a world scale, and I say this while making no concessions to our utterly despotic and exploitative militarised ruling class.

Let’s be clear: dominant policy paradigms on the climate crisis have originated in the same (western) aid industry that has presided over neoliberal orthodoxy and continue to be reproduced by it too. Our ever-ready-to-ape the west bureaucrats, political leaders and de facto khaki overlords typically just play along, making sure to accommodate the niceties of policy, including corporate social responsibility (CSR).

My purpose is not to suggest all players in this otherwise sordid story are the same. The Pakistani delegation at the last global climate summit – COP27 – was widely acknowledged to have led the G77 countries at the negotiating table, securing an important ‘victory’ in the last-minute announcement of a loss-and-damage fund. But symbolism aside, there is every chance that the loss-and-damage fund will be much ado about nothing, as so many previous climate financing initiatives have proven.[4]

As I have already suggested, it is in any case important to be cognisant that climate politics is not only about the extent to which historic emitters (primarily western countries) quite literally pay up. Arguably even more important is to redress existing social and economic processes that are exacerbating the crisis on a daily basis. Greenhouse gas emissions are still not being curbed with anything like the urgency that virtually all scientists insist is necessary; almost 85% of the world’s energy consumption is still drawn from fossil fuels.

Pakistan’s domestic political economy is a microcosm of global trends. Our energy mix features a huge reliance on imported oil, while the contribution of thermal and coal-fired power is growing rapidly. Over the past two decades, Pakistan’s contribution to global carbon emissions has tripled (from 0.3% to 0.9%). This may still be small in the relative scheme of things, but it reflects a clear – and destructive – trajectory which demands attention.

Prevalent economic orthodoxy in Pakistan is almost completely unconcerned with medium and long-term ecological effects, not to mention effects on working class segments. The highest return industries – like construction, real estate, tourism and mineral extraction to name a handful – are highly destructive in environmental terms. The 2022 floods showcased clearly how these industries greatly exacerbated the devastation of local ecologies and working class communities, alongside donor-funded mega water and other big infrastructure projects.

All of this simply clarifies that the climate crisis is not ‘natural’. There are long-term geological, epochal explanations for change in planetary temperatures but there is also no question that human-made economic and political systems are the fundamental trigger for the nature and scale of human and environmental destruction in our current conjuncture.

This brings me back in closing to the question of climate politics. The current state of the ‘climate justice’ movement is simply not sufficient to cope with what confronts us because the dominant tendency is to compartmentalise the question of ecology rather than acknowledge its inextricable link to the larger structural dynamics of capitalist imperialism.[5] For us in Pakistan, the only meaningful way to address the climate crisis in the medium and long-term is to create mass consciousness within our young, working population. Simply, we need to build an anti-imperialist class politics in both metropolitan Pakistan and the ethnic peripheries which centres the question of ecology. Otherwise we will remain at the behest of policy ‘experts’, to our collective detriment.

The author is an Associate Professor, Political Economy, at the National Institute of Pakistan Studies – Quaid-i-Azam University. He is affiliated with the Awami Workers Party and can be found on Twitter as @AasimSajjadA.

[1] The argument in this article is a summary of a soon-to-be-published and far more detailed exposition : A.S. Akhtar (2023) ‘Climate Breakdown in Pakistan: (Post) Colonialism on the global periphery. Journal of Contemporary Asia https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2023.2279952

[2] Nancy Fraser (2021) ‘Climates of capital’. New Left Review 127

[3] A prominent example of carbon credits in Pakistan is the planting of mangrove forest in coastal Sindh, the ultimate costs and benefits of which remain ambiguous. See https://www.npr.org/2023/11/10/1208201179/pakistan-is-planting-lots-of-mangrove-forests-so-why-are-some-upset

[4] See Ali Tauqeer Sheikh. ‘Elusive Climate Justice’. DAWN, 9 November 2023

[5] Take, for instance, how Greta Thunberg has been vilified for taking a position on Israel’s genocidal attack on the occupied Palestinian territories after 7 October 2023.